More than the work of any major director since Howard Hawks, John Carpenter’s films have undergone a unique "second life" -- a period of intense re-evaluation…and new-found appreciation.

Even the classic Halloween (1978) originally drew bad reviews and nearly faded into obscurity until a laudatory Village Voice review by Tom Allen, and a well-timed holiday release rescued the film's reputation. Today, Halloween is a fixed star in the horror firmament; even a companion piece for Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960).

Likewise, Carpenter’s The Thing (1981) was ignored by audiences and vilified by critics in the summer of E.T. (1982). Carpenter was even termed a “pornographer of violence” by some short-sighted critics because of the film’s intensity and pioneering (though admittedly gruesome...) special effects.

Yet by the 1990s, The Thing was exerting enormous influence on the genre in Hollywood productions almost too numerous to list. From The X-Files (“Ice”) and the main adversary of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine -- the shape-shifting “Dominion” (detectable only by blood test…) -- to the T-1000 in Terminator 2 (1991), Thing imitations were practically ubiquitous.

In recent years, critical estimations of In the Mouth of Madness (1994), They Live (1988), The Fog (1980), Vampires (1998) and Ghosts of Mars (2001) have also trended positive. But perhaps it is the director’s 1987 Nigel Kneale homage, Prince of Darkness that has witnessed the most meteoric rise in appreciation. Once derided as "second rate" and "klutzy," the film is now beloved for its brawny narrative twists, not to mention Carpenter's crisp direction.

The second movement of Carpenter’s so-called “Apocalypse Trilogy” (a cycle including The Thing and In The Mouth of Madness…), Prince of Darkness is elegantly shot, suffused with a gloomy, unsettling vibe of cerebral terror (the more you understand, the more afraid you feel…) and punctuated with periodic jolts or "stingers" of extreme intensity. It is, as L.A. Times critic Michael Wilmington opined, a film "filled with graceful, gliding tracking shots, and icily precise Hitchcockian setups of the bleak decor and scary effects." (October 23, 1987).

Prince of Darkness also features one of Carpenter’s most memorable, arresting and pulse-pounding soundtracks. The score’s “ominous intonations…grab you and take command of your heartbeat.” (Allen Malmquist, Cinefantastique Volume 13, # 2, March 1988, page 117).

In all, this Carpenter film fires on all cylinders, and holds up exceedingly well on repeated viewing. At the film's heart is a discussion of science as the new "faith;" and an examination of a population -- an alienated population -- searching for spiritual and emotional meaning in a world apparently devoid of it.

He Lives in the Smallest Part of It

Prince of Darkness features a number of John Carpenter touchstones, both visual and thematic. First and foremost, this is a siege picture (like Assault on Precinct 13 or Ghosts of Mars), meaning that the action focuses on a small group of protagonists inside fighting off superior forces outside.

The abandoned police precinct of Assault has become the abandoned Church -- Saint Godard's -- of Prince of Darkness. In both scenarios, the location of the battle is important. The buildings are relics; ones without contemporary meaning or importance. Society has passed them by in both cases; they are symbols, essentially, of impotent infrastructure or bureaucracy.

Writing for Monthly Film Bulletin in May of 1985, Philip Strick compared the two Carpenter films in a way that is illuminating for our discussion: "With Prince of Darkness, the siege of Assault on Precinct 13 is vividly reconstructed: the derelict fortress, the comfortless corridors, the silent army in the night outside, the collapse of logic and security."

You may recall that the oft-repeated "siege" element in Carpenter's films is an homage to the cinema of Howard Hawks, notably Rio Bravo (1959).

But Prince of Darkness is also an homage to one of Carpenter's favorite writers : Nigel Kneale. Kneale was the prime talent behind the British Quatermass films of the 1950s and 1960s (The Creeping Unknown, Enemy from Space and Five Million Years to Earth). His films (as well as TV serials) popularized the notion that threats mistaken as being of supernatural origin are actually...extra-terrestrial. In Five Million Years to Earth (1968) it was a Martian psychic force, not the Devil, sweeping through London, and so on. Carpenter resurrected this concept for Ghosts of Mars in 2001, but first he employed it in Prince of Darkness.

In Prince of Darkness, Jesus is an ancient astronaut, and Satan and his Father (the Anti-God) are also extra-terrestrials. In a tip of his hat to Howard Hawks, Carpenter edited the film Assault on Precinct 13 under the name "John T. Chance," the name of John Wayne's character in Rio Bravo. Likewise, Carpenter penned Prince of Darkness under the name "Martin Quatermass." Quatermass, of course, is the protagonist of Kneale's most famous works.

Prince of Darkness also evidences Carpenter's distinctive anti-authoritarian voice. Here, the Catholic Church has hidden the truth about the nature of Evil for 2000 years. "We were salesmen," says Pleasence's priest with disgust. "We were selling our product."

In various films -- as we've seen -- Carpenter also went after movie critics and Reaganites (They Live), religious fundamentalists (Escape from L.A.), and even used the Catholic Church as a target again in Vampires. There, another Catholic sect was hiding a different Devilish secret: a black crucifix that created the world's first vampires.

Where Prince of Darkness pinpoints so much new energy, however, is not in these commonly-found Carpenter homages or themes, but rather in the endless possibilities of Quantum Physics. It's a whole new playground for the director, and he makes the most of the territory. The film discusses every important concept from Schrodinger's Cat to "causality violation" (time travel), and does so with a sort of breathless, fast-paced intelligence that challenges the audience to keep up.

Let’s Talk About Our Beliefs, and What We Can Learn From Them…

Prince of Darkness begins with the discovery of an ancient and secret Catholic sect known as "The Brotherhood of Sleep."

The guardian priest of this mysterious sect dies while clutching a miniature box containing a key; a key to the basement of a rundown Church in poverty-stricken L.A. called Saint Godard's.

There, upon an altar in the basement...is a seven million year old canister of volatile, swirling fluid. The liquid is, in fact, Pure Evil: Satan himself.

In hopes of comprehending and defeating this unusual threat, a Catholic priest (Donald Pleasence) teams up with Professor Birack (Victor Wong), a teacher of quantum physics at the Doppler Institute of Physics.

Along with a group of dedicated graduate students -- including lonely Catherine Danforth (Lisa Blount) and Brian Marsh (Jameson Parker) -- the man of science and the man of faith spend the weekend at the old church and undertake a study of the canister and the liquid, as well as the corrupted Latin palimpsest that details its history and secrets.

Over a long, horrifying night, as revelation follows revelation, the forces of darkness invade the Church. As the devilish, pre-biotic liquid "self-organizes," it assumes psychokinetic control over small organisms (such as insects) first, then L.A.'s wretched homeless, and, finally, it makes zombie minions of many of the graduate students themselves.

The evil liquid also selects a human host, Kelly (Susan Blanchard), and plots to bring its demonic father -- the Anti-God -- into our dimension.

At the same time, all the graduate students experience a recurring nightmare: a tachyon S.O.S. warning from the year 1999...

Very much like 1982's The Thing, John Carpenter's Prince of Darkness concerns flawed, lonely, awkward human beings living in a world in which there is no real faith or human inter-connection. In fact, Prince of Darkness repeats verbatim a line uttered by R.J. McReady (Kurt Russell) in The Thing: "Faith is a hard thing to come by these days."

As in that earlier film the line is spoken by Carpenter's unconventional protagonist and voice for the audience, here a graduate student in quantum physics named Brian Marsh.

The problem is that in a world of advancing science and human knowledge, the old platitudes of religious faith and belief seem antiquated and stale. At least until dressed up with such scientific candy-coating as "differential equations," "tachyons," "indeterminancy," and the like. Yet importantly, those "new" scientific concepts don't tell us who we are (or who we should be...) in the same authoritative sense that old-fashioned belief systems did.

Thus...a void.

Carpenter -- ever the visual artist -- finds an imaginative way of expressing this crisis in spirituality.

As Pleasence's priest views St. Godard for the first time, the camera presents an establishing view of the church from behind an old iron gate, and a holy cross -- a Catholic Crucifix -- can be seen jutting heavenward from the church's roof. Yet above the church is another gate slat, this one horizontal in direction. In other words, the cross (representing religion or faith) is boxed in on all sides, from above and from left and right. Visually, it is trapped --confined and caged -- by its inability to answer the questions that so many people ask in today's world.

Professor Birack -- a wise elder and interpreter of the quantum runes -- seems aware of these problems in human connection, and he seeks amongs his students -- again according to the dialogue, -- "philosophers" rather than "scientists."

Philosophers, he understands, will understand how to place scientific knowledge within the context of man's spiritual or emotional world; whereas scientists, by implication, may not.

In Birack's students, we see disciples in waiting: lost souls who, for the most part, have forgotten the art of being human.

Instead, they have come as boxed-in as the crucifix over the church. They have labeled themselves using the prevailing and simplistic lingo of their culture. "I'm a confirmed sexist," Brian tells Catherine proudly while trying to court her, unaware of how silly and bigoted he sounds.

Later, Walter (Dennis Dun) tells a racist Jewish Mother joke ("I said rich doctor, not witch doctor!"), and also comments, condescendingly that Lisa, the team translator, could "pass for Asian."

This is a world in which it doesn't matter so much that a woman like Susan (the radiologist) is married, but rather the degree of her marriage ("how married?" a potential suitor asks).

Thus communication between people -- especially between people of opposite sexes -- is dominated in Prince of Darkness by what Catherine terms "miscues." These are wrong, defensive interpretations based on pre-conceived notions of others and even a pervasive non-understanding of self.

In his essay, "John Carpenter: Cinema of Isolation" scholar John Thonen saw these graduate students as "selfish," and "lifeless" (Cinefantastique, Volume 30, Number 7/8, October 1998, page 71).

What these lost souls seem to lack is the very thing religion once provided for many: a sense of belonging, a sense of man's innate goodness. These young scientists, as the film notes, get romantic when discussing The New Faith (Quantum Physics) but "clam-up" when it comes to talking about emotions, feelings and humanity. Perhaps that's because science provides no guide-lines, no rules, no equations in such matters.

Catherine and Brian are seekers of truth and more than that, they are seekers of love...which is something more meaningful than just good sex (which ironically, is their first connection). Catherine desires to know "what the numbers mean," a search beyond scientific jargon, and Brian's obsession with card tricks represents a need for an understanding of life beyond mere probability tests; in something like...luck.

Each character has an idea of what specific path will lead them to personal enlightenment, but what they wish to make room for is the person -- the other -- who may bring them, via philosophies unknown and unexpected, to the missing piece of life's puzzle. To love. To real intimacy.

The tragic love story in Prince of Darkness plays out, interestingly enough, as a modern Christ analogy.

Because of her burgeoning relationship with Brian, Catherine is finally open to love, to giving. Ultimately, she sacrifices herself to save mankind. She vanquishes the evil, but at the cost of her own life and future.

"She died for us," Birack states succinctly, putting Catherine's sacrifice in decidedly religious, Christian terms. Catherine knew what was at stake and made a conscious decision to consider others above her own well-being and survival. She saved, literally, a wicked world (one controlled by the Anti-God). She thus changed everything, preserving our future. Her Gospel, perhaps, is the message heretofore incomplete: the one beamed back through time (a causality violation) as an unconscious message.

Will that message be different after her choice to save our world, or will it simply cease to exist all together?

No Prison Will Hold Him Now

Prince of Darkness debuted in the Age of AIDS, in 1987. This was the very year, in fact, that President Reagan made his first public statement on the epidemic. It was also the year that the formerly promiscuous James Bond 007 (Timothy Dalton) became a one-woman kind of guy in The Living Daylights.

The AIDS epidemic (as it was understood at the time) serves as an important backdrop to Carpenter’s film, since the “Evil” force depicted here is a fluid passed from person-to-person (usually mouth-to-mouth). Susan infects Calder by kissing him and forcing the evil fluid down his throat.

Likewise, she contaminates Lisa in a sexually-charged sequence. As Lisa reclines on her bed, supine, Susan mounts her -- ascending into a dominant position -- straddling her. She then ejaculates the fluid into Lisa's protesting, open mouth.

In the case of both AIDS and the Devil Liquid, transmission occurs through what appears to be sexual behavior; and the danger is carried in the equivalent of bodily fluids.

AIDS was largely seen originally (in the very early 1980s) as a "gay" disease, because it decimated that population first. If you look at the pattern of transmission in Prince of Darkness, you may note that same-sex transmission is highlighted. Susan infects Lisa. Susan and Lisa infect Kelly (all women). Professor Leahy (Peter Jason) and Calder (both men...) go after Brian.

The one instance in which a woman does infect a man (Susan to Calder) could be read as representing another sexual taboo: interracial coupling.

And come to think of it, Susan -- the first to be infected and spread the disease -- is married; thus acting out, essentially, an infidelity.

What we're talking about here then isn't just sexual behavior then but perhaps sexual misbehavior. Remember, The Thing too featured a single sex population in peril and posited Evil as an easily-transmitted disease; one "hidden" in the blood. In that film as well as in Prince of Darkness, Carpenter reflects American society's rampant fear of and paranoia about AIDs, about disease transmitted from person-to-person during promiscuous, impulsive acts.

Another important context underlining Prince of Darkness involves the 1980s epidemic of homelessness. By 1983, there were 35 million Americans living in poverty, some five million more than when Reagan had been inaugurated in January 1981. Reagan's economic policies involved what The Christian Science Monitor termed "deep budget cuts in the social service area" in order to lower taxes for the wealthiest Americans. The result was that more and more people lost their homes. Reagan once stated that many of these unfortunates were “homeless by choice.”

In Prince of Darkness, it is these homeless who first become human minions to the Devil...an army of streetwalkers and hobos who -- ostensibly aimless -- have found malevolent purpose. Idle hands and all.

Carpenter returned to the the theme of poverty and the homeless in his next film, They Live (1988), setting much of the action in a Shantytown called "Justiceville."

Say Goodbye to Classical Reality

Carpenter's Prince of Darkness screenplay asserts a "universal min,d" or God if you will. However, because this is a Kneale-ean homage anchored in science, it also asserts the Laws of Physics. In particular, the film reminds us that every particle has an opposite or anti-particle. Therefore, if there is a universal mind or God, by inference there is also an anti-God.

In the film, a shorthand for this duality is quickly established via mirrors, via reflections. Accordingly, much of Prince of Darkness visually and contextually deals with doubling, opposites, and mirror images. The mirror becomes the portal to the other world; where our "opposites" exist.

Birack and Pleasence's Priest are mirror images of sorts, possessing contrasting world views (science vs. religion) and Carpenter even uses mirror image compositions throughout the film, most notably during Brian's "test" leap into the alley beyond the church, and the subsequent attack of the homeless "antibodies." The film cuts to opposing reverse angles moving in on Brian from both sides. It's a visual mirror, with Brian as our point of reference in both shots, from both angles. Brian's prominent placement in the frame even presages Prince of Darkness's electric, portentous climax: a further "test" by Brian...this one staged as he reaches out for his own, possibly malicious anti-self in a mirror.

These final images resonate. They get under the skin. They promise so much yet explain so little.

As Brian reaches for the mirror, gazing into his own reflection, the film's many themes converge. He is not only wondering if Catherine is watching him from the other side -- from the anti-verse -- but he is looking into his own face -- sweaty and pale -- and seeking answers.

Brian is wondering, perhaps, if, the evil, the contamination could pass to him next. Only a moment earlier, he imagined himself in bed beside a rotting corpse...(the ultimate fear of the AIDS era...) and the uncertainty, the fear of infection, is palpable.

It is this moment that Carpenter leaves us to ponder as the film concludes: a close shot of a groping hand reaching for (but not actually touching...) a mirror; the portal to darkness.

Prince of Darkness remains one of John Carpenter's most frightening films, not merely because of the superb soundtrack, the AIDS-subtext, or the clever use of Quantum Physics, but because the screenplay spotlights how much we take for granted in our daily lives.

In Prince of Darkness we witness a world where logic is of no use (it collapses on the subatomic level...) and in which Evil is Real.

There is indeed an order to the universe, John Carpenter reminds us...but it's not at all what we had in mind...

Part

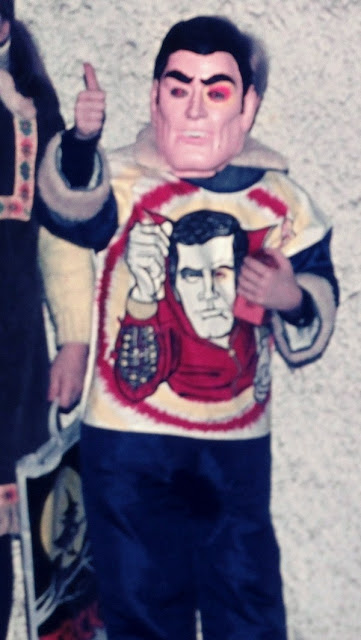

of the fun of Halloween in the 1970s involved those classic, if flimsy, Ben

Cooper costumes of the era. One year, I went out trick-or-treating as Ben

Cooper’s Steve Austin, the Six Million Dollar Man. As you can tell from the photograph, however,

I look more like President Ronald Reagan than Colonel Austin.

Part

of the fun of Halloween in the 1970s involved those classic, if flimsy, Ben

Cooper costumes of the era. One year, I went out trick-or-treating as Ben

Cooper’s Steve Austin, the Six Million Dollar Man. As you can tell from the photograph, however,

I look more like President Ronald Reagan than Colonel Austin.