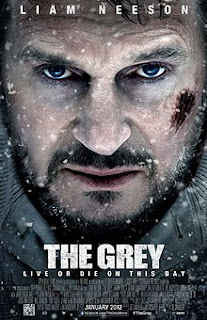

At first blush, Joe Carnahan’s The Grey (2012) appears as if it’s going to be an action/survival/horror film that deliberately compares human and animal natures. That leitmotif is developed well as the alpha males in both a human “tribe” and timber-wolf pack assert their authority over unruly members.

However, The

Grey emerges a full-throated, staggeringly emotional work of art

because it transcends even that admirable thematic conceit, and comes to meaningfully

grapple with the most important questions regarding our existence and mortality.

In short, this is an action film obsessed

with death, about different viewpoints regarding death, and about the existence

(or non-existence) of God and the afterlife.

Dark, introspective and

yet hauntingly beautiful and profound, The Grey, in my opinion, is the finest

film of 2012…at least at this half-way point.

“Who do you love? Let them take you…”

The Grey follows the harrowing final journey of John Ottway (Liam Neeson), a man who -- following the death of his wife Ana (Anne Openshaw) -- has all but exiled himself from human civilization. Ottway now holds twilight jobs at isolated Arctic oil refineries, protecting the roughneck workers there from wolf incursions. He kills wolves for a living, in other words, and he protects people he doesn’t even like.

Early on, and in voice-over

narration, Ottway notes that he lives “like

the damned do,” and one lonely evening he nearly commits suicide. But something inside him -- a steely resolve spurred by the sound of a

wolf howl -- inspires him to go on, to keep living.

The very next day, on a

crowded plane journey home to Anchorage, a catastrophe unexpectedly occurs. The plane goes down in swirling snow and ice. The crash is dramatized by Carnahan in the

most anxiety-provoking terms imaginable: Ottway is literally dragged out of a peaceful

dream (of his wife) and back into grim, unacceptable reality and the ride of

his life.

After surviving the

crash, Ottway helps one mortally-wounded survivor, Lewenden (James Badge Dale)

achieve a semblance of peace as death slides over him. “Let it

happen,” Ottway urges the dying man with decency, compassion, and

understanding. Here, Carnahan’s camera

doesn’t turn away from Lewenden’s last seconds, and we must watch as the man

transitions from disbelief and throat-clenching desperation to, finally,

peace. It’s not for the faint of heart,

and there’s no ameliorating movie nonsense to make the moment palatable or in

any fashion comfortable.

Soon, the remaining survivors

are menaced by a new threat: territorial timber wolves. Ottway fears that the plane crashed near the pack’s

den, a fact which could explain their overtly aggressive behavior. Realizing they can’t stay, the survivors of

the plane crash -- carrying the wallets of the dead back to civilization -- set

out for a line of trees, hoping to leave the wolves behind. Meanwhile, Ottway is challenged for dominance

in the group by the surly, loud-mouthed Diaz (Frank Grillow).

With the wolves

constantly in pursuit, Ottway and his fellow men attempt to survive other

natural dangers, including an ice storm, a chasm, and a roaring river. As the group’s numbers diminish, Ottway

confronts his own feelings about death.

Desperate to understand

some purpose for his suffering, and for the suffering of his wife, Ottway calls

out for God, for a sign: “Do something! Do something! You

phony prick fraudulent motherfucker. Do something! Come on! Prove it! Fuck

faith! Earn it! Show me something real! I need it now. Not later. Now! Show me

and I'll believe in you until the day I die. I swear. I'm calling on you. I'm

calling on you!...”

“Fate didn't give a fuck. Dead is dead.”

In Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1960), a grieving father, Dr. Tore (Max Von Sydow), gazed Heavenward and asked God for some justification of the trials that man goes through in this world.

Dr. Tore had lost his

daughter, Karin, and murdered the herdsmen responsible for her death. “You see it and you allow it! The innocent child’s death and my revenge,

you allowed it! I don’t understand you,” he cried.

But Tore’s faith in the

Lord was validated when a bubbling spring miraculously appeared at the very

site where his daughter died. Dr. Tore

asked for the meaning of life, and God answered him in the affirmative.

In The Grey, John Ottway, a

man who has lost his wife and witnessed the death of his fellow roughnecks,

also asks God for a sign. By contrast,

however, he is rewarded negatively. He

receives not an affirmation, but a horrible punch-line that makes a mockery of

his struggle, and of the struggles of all his fellow men.

This final punch-line

-- which involves the particular destination

of Ottway’s long trek through the wolf-filled woods -- might be interpreted

two ways. In the first case, Ottway is

indeed among the “damned” and so God has meted out a devilish punishment for

him and the other sinful “outsiders.”

Or – and I suspect this is the case – the

answer is simply that there is no God.

Instead, there is only

a savage, uncaring universe. The answer to Ottway’s query is that there are

only further trials to survive and if he wants to do it, he better get to it…himself. In

other words, life is struggle, and you either survive for the sake of living

(because there is no after life…), or you lay back and, in Ottway’s words, let

death “slide” over you.

Obviously, something in

humanity feverishly resists death, and struggles against it, even though death

is inescapable for everyone. In a very

real sense, this idea is what The Grey meaningfully concerns, as

each of the roughnecks must reckon with death on a personal and intimate basis.

Accordingly, each of

the characters in the film is well-drawn, going well beyond cinematic clichés,

and thus the audience gets a strong sense of those who face death. For instance, one character, named Talget

(Dermot Mulroney) recounts a touching story about his young daughter, and how

she permits only her daddy to cut her long hair. No one else can do it. Upon Talget’s confrontation with death, that

imagery is resurrected in an incredibly moving phantasm; a scene that is

simultaneously heart-breaking and also tinged with a feeling of acceptance.

When everything comes

to an end, when death finally arrives, Talget’s vision is of something positive

and beautiful from time spent on this

mortal coil. There is no white

light, or tunnel, and no transition to Heaven.

There is only the final blast of memory from this lifetime, right here…of

a meaningful love.

Another character,

Diaz, starts the film as a dedicated nemesis for Ottway as well as a threat to

his position as alpha dog. But throughout

The

Grey, Diaz develops into a person audiences can sympathize with. Near the climax, he gets to a point where he

can no longer continue the trek southward, and so he makes a decision about his

life; a decision about how and where he wants it to end. “I just

had the clearest thought,” he declares with a sense of peace. “I’m

done.”

The decision Diaz makes

while looking out across a gorgeous northern landscape is not based on

weakness, but upon strength….and grace. We can’t control the fact that we will,

eventually, die. But we can control, to

some extent, how we face death.

The Grey sets up a very interesting and tension-filled dynamic regarding death, and about knowing when to hold on and when it is time to surrender. For example, the characters all hold onto their humanity by carrying with them on their trek the wallets of the dead. The wallets are filled with photographs of loved ones. These photos are reminders of identity and also reminders that the dead once existed and walked this earth. Eventually, however, these keepsakes of another life must be put down, because the wild is not a place of civilization, and the wallets are an indication of false hope, of a destination that will never be reached. The rapacious wolves carry no keepsakes of the dead, by contrast.

At the center of The

Grey -- holding it all together with his special brand of melancholy

ferocity and intelligence -- is Liam Neeson. He’s no stranger to tragedy, and

his performance here represents something of a career zenith. Ottway is a man haunted by the death of his

wife, drawn to death like a moth to the flame, and yet who – moment after moment – rages against

death’s inevitability. He just won’t

stop fighting…even if the universe seems to be playing that cruel joke upon

him. Neeson must reckon with his

character’s cunning, anger, regret, and also with the absurdity and inherent

meaninglessness of Ottway’s situation.

Ottway is the film’s gravity pool, the thing which everyone and

everything else must orbit, and Neeson gives a commanding, heartfelt

performance.

In examining Ottway’s

belief and situations, The Grey, in some crucial ways,

feels like a character piece. It

transcends expectations and emerges as the horror genre’s The Tree of Life

(2011). We are asked to examine how

Ottway got here. What, simply, does his personal

journey mean?

To help us understand,

we witness in flashback Ottway as a young boy with his (now dead) father,

reading a poem about life…and death. We

see flashbacks of Ottway with his dying wife, as she implores him to be

unafraid. Through it all, we get the sense of a life that boasts a shape, a

direction, and a purpose, but that all these elements are ambiguous and outside

our capacity to understand.

Is

Ottway damned? Is he saved? Is he just one incredibly unlucky bastard?

In reckoning with Ottway

and his life, we are forced to gaze at our own lives and weigh meaning. Or,

perhaps, craft our own meaning from it.

And yes, this tactic represents the pinnacle of what a good horror film

can achieve. The Grey holds up a mirror and makes us wonder: what would you do? How would you react?

When the wolves finally

come to carry us away to oblivion, will we face that final moment with

acceptance, delusion, or with resistance?

The Grey explores almost every variation of death’s coming,

almost as if offering helpful examples.

We witness characters face fate with grace, like Diaz. We see them face death in delusion (like

Burke, who dies of hypoxia). We see them

die with sad acceptance, like Talget.

And then there’s this kind of willful, almost instinctive ferocity in

Ottway.

In some senses, Ottway’s

resistance to death grows from that poem he knew and internalized as a child,

which goes: “Once more into the fray/Into

the last good fight I’ll ever know/Live and die on this day.” His very ethos seems encoded there, in

that mantra. He lives life moment by moment

because “you want that next minute more

than the last.” That’s “what makes life fighting for,” the

acknowledgment that life here is all there is.

Again, I interpret this

as a strongly existentialist, nihilistic argument. Why doesn’t

Ottway let the wolves or the environment take him, even with his wife beckoning

him so warmly in his dreams?

Because Ottway

understands that when he dies nothing but oblivion shall follow. As much as he is tortured by his wife’s

death, he knows that she lives on only in

his memory. If he dies, then they

are both dead to the world, gone and forgotten.

Choosing to live and fight on is thus a way – the only way -- of keeping her memory alive. His passage into oblivion won’t permit that

outcome. And so Ottway holds on, in some

cases beyond reason, and certainly beyond the endurance of most men.

When Ottway tells the dying to let those they love "take them," he is not acknowledging an after-life with pearly gates, angels and harps, and that's an important distinction. He is asking them to reflect upon their loved ones in their final moments, and go out of this world and into the dark of annihilation thinking of that love. Because that love is the most important aspect of the human experience. The connections we make here are what matter, not fantasies of an eternal, paradise-like after-life.

The Grey is a beautiful, thought-provoking film, and one that also happens to feature some incredibly intense, incredibly graphic violence. But unlike Shark Night, for example, the violence here truly matters because Carnahan and writer Ian MacKenzie Jeffers are able to distinguish the “damned” roughnecks in ways that matter, and affect us as viewers. These guys are rough and tumble, yes, but they are also fathers trying to eke out a living for their families. They are also brothers and sons, and some of them just don’t want to die without getting to have sex one more time. These men may not matter to society at large, but they matter to us because of our common humanity.

The Grey might be considered a man against nature film, but the wolves, in some way, are mere symbols that help John Ottway reckon with the meaning of life. They are voracious, monstrous representations for impending death: the big bad wolf on your heels. In the cold of the Arctic -- with all the trappings of society absent -- this is a story of what life on Earth is truly about. Haunting, brutal and

emotionally rich, The Grey transcends genre and speaks directly to

the questions that matter most to human beings.

Am I going to live or

die today?

And when death comes

for me, how will I face it?

John - Nice review; you always get more out of movies than I ever do. I recently watched The Grey as well and was struck by the inevitable nature of man to fight amongst ourselves. Here they are in a remote, harsh environment with little food AND giant wolves, and yet there is still struggle for power among the survivors. It happens often in movies, but it reminded me of The Thing where the survivors were questioning MacReady's motives. If I were in a similar situation I would do everything I could to give the external threat priority!

ReplyDeleteWithout giving any spoilers, just wanted to remind you that there is a very short post-credits scene.

Hi Chadillac,

DeleteThat's a great insight to compare The Grey to The Thing. I think there are real commonalities there: isolated location; all male-cast, a threat from outside; survival as, perhaps, unrealistic goal, and even the idea of what it means, really, to be a human being. And you're right that in both films, the humans can't seem to get it together enough to mount a joint defense against the elements/enemy.

Interesting observation. I think it is inevitable that man fights himself. Everyone in The Grey (and The Thing) has a stake in continued survival, and believes that he knows the best way to reach that goal. We're scared that someone might not be what they appear to be, either human, or in the case of the Grey, capable.

Thanks for reminding the readers here to stay until after the end-credits. I should have mentioned that in my post!

best,

John

Prior to this, ‘Narc’ was my favorite film by Joe Carnahan. I daresay this one has squeezed by it. The location work was extraordinary, and the CGI was kept to a minimum (as Liam Neeson reported, the wolves were mostly animatronic). But, it is the story, direction, and performances that made this movie quite remarkable. It really spoke about men in a number of ways most of us guys will recognize, or quietly keep to ourselves. As my colleague over at Fogs Movie Reviews said, it really is the “first awesome movie of 2012.” You've given it a truly fine review for a great movie. Thanks for this, John.

ReplyDeleteFirst, Happy New Year John.

ReplyDeleteSecond, finally watched this film. It is everything you said. It was definitely one of the best of the year.

Also, speaking of man in the wilds, loved your recent take on Prophecy too. What a great film. That was one of the films I had on a snowy VHS tape back in the day. It was in heavy rotation in my neighborhood.

I hope all is well.