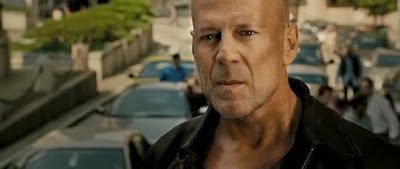

John

McClane enters the 21st century – not to mention the post-9/11 age

-- in Live Free or Die Hard (2007), the first PG-13 entry in the

durable action franchise.

Although

it’s difficult to be particularly judgmental of the generally entertaining Live

Free or Die Hard (2007) -- especially given the quality of its

follow-up, A Good Day to Die Hard (2011) -- this movie also provides ample

evidence to suggest the franchise’s best days are behind it.

In

particular, Live Free or Die Hard features a bland, forgettable villain, played

by Timothy Olyphant, and regurgitates, almost precisely, the format of Die Hard

with a Vengeance by eschewing a single location story and partnering up

McClane with another bicker-some partner, in this case one played by Justin

Long. Where Samuel Jackson’s Zeus Carter battled McClane over issues of race, Long’s character offers a generational challenge to the put-upon cop.

Live

Free or Die Hard’s

greatest drawback, however, is that this third sequel to McTiernan’s 1988

classic transforms McClane into a veritable superman, one able to fly cars into

helicopters and surf a military jet in flight. The whole idea of the every-man

with a “die hard” personality is lost, to a great extent. And since Willis plays

McClane with greater restraint than ever before, we don’t even have his darting

eyes and furtive movements to suggest is he in constant jeopardy, or afraid for

his life.

Certainly,

there’s a great scene in Live Free or Die Hard wherein

McClane describes exactly what it costs him, personally and emotionally, to be

a hero, but that scene -- firmly planted in reality -- is but a passing blip in

a film that, intentionally or not, makes the case that McClane is as

indestructible as Arnie’s Terminator.

Len

Wiseman directed Live Free or Die Hard, and the movie was a huge success at the

box office. The film is no embarrassment (again, in light of A

Good Day to Die Hard…) so this second-guessing of ingredients is largely

academic. Still, this entry in the canon

accelerates Die Hard’s descent towards generic, mindless action franchise.

It may not be a bad movie overall, but it is another rung down the ladder

towards mediocrity.

The

fact that the movie’s PG-13 rating doesn’t even permit McClane to utter his

immortal catchphrase -- “yippee kay yay,

motherfucker” -- is an omen, perhaps, that business and demographic concerns

have finally eclipsed artistic ones in the Die Hard universe.

“You’re

a Timex watch in a digital age.”

After

arguing with his daughter, Lucy (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), divorced cop John McClane

(Willis) is tasked with bringing in a hacker, Matthew Farrell (Justin Long) who

may have knowledge of an escalating cyber-attack on financial markets and the

government of the United States.

At

the same time, however, assassins are sent to kill Matt, and John is once again

in the wrong place, at the wrong time, facing a terrible threat.

As

Matthew explains to John, a group of well-organized, well-funded hackers are

attempting a “fire sale” attack on the U.S.

When

John gets Matthew to Washington D.C., he learns that the culprit is the once well-respected

Thomas Gabriel (Timothy Olyphant), who pointed out to the government its lack

of defenses in the case of a cyber-attack.

Now

Gabriel is showcasing that lack of defense, but in reality, is planning a huge

cyber-robbery.

When

Lucy is kidnapped by Gabriel, John and Matthew must work together -- despite generational

differences – to short-circuit Gabriel’s escalating attack and save the

day.

They

will require the help of an expert hacker, a guy called Warlock (Kevin Smith).

“Another day in paradise.”

I’ve

written about this concept before, but in the first decade of the twenty-first

century -- just around the time of Live Free or Die Hard’s production,

actually -- TV and film switched places; suddenly switched paradigms.

Suddenly,

television was the venue for intelligent, niche programming that would never

have survived on a “big” network in earlier eras. Think Dexter (2006-2014), or Mad

Men (2006-2015). And movies, which had survived and thrived

through an independent film movement of great quality in the 1990s, began to become

horribly, catastrophically homogenized, so as to attract all possible

demographics and win the all-important opening weekend sweepstakes.

One

can argue why this switcheroo occurred and remains in place today, but Live

Free or Die Hard feels like it bears the weight of the switch.

Remember

how Die

Hard had all those weird-moments with pin-up girls, and Christmas party

revelers snorting coke and having sex?

There

are no moments like that in Live Free or

Die Hard.

Remember

how Zeus Carver and John McClane shared some really tough, really frank

conversations about race relations in Die Hard with a Vengeance?

There

is nothing so edgy or frank, or for that matter, real, in Live Free or Die Hard.

Remember

how John McClane’s catchphrase alone gets each Die Hard film a hard R

rating?

The

character’s very catchphrase is not uttered in the theatrical version of Live

Free or Die Hard.

It

all makes one wonder if Die Hard was sold in a “fire sale”

to Walt Disney Studios.

The

switch to a more generic, safer approach, ill-suits the Die Hard franchise,

because the films concern a stubborn man who is not easy to live with. McClane

is confrontational, and, well, edgy. John makes enemies wherever he goes

because he is “die hard.” He doesn’t tolerate fools, and he knows how to get

things done. If someone isn’t helping him with a problem, they’re part of the problem.

The first film made his world view abundantly clear, especially in terms of the

“Dwayne” character, a bureaucrat and fool.

So if you take away John’s ability to cuss, and you’re already downgrading

the individuality of the man, and his distinctive viewpoint.

But

much worse than censoring John’s ability to swear, is the film’s insistence on

censoring John’s ability to bleed, or break bones.

In

Live

Free or Die Hard, John McClane is thrown off a jet in mid-air and keeps

going. He doesn’t miss a beat.

John’s

timing and reflexes -- while traveling 55 miles an hour -- are so great that he

is able to “kill a helicopter” by launching a car at it.

These

are not the feats of a “die hard” police man; these are the feats of a

superhero.

Another

way to put it involves the concept of gravity. In the earlier Die

Hard movies, John accepts the limits of gravity, and works within those

limits to achieve his desired ends. He

sends C4 explosives strapped to a chair down an elevator shaft to blow up

terrorists with an RPG. Gravity is his

friend. The chair drops eighty or so

floors via the auspices of gravity. John delivers a bomb, in other words, with

gravity’s help.

The

set-pieces in Live Free or Die Hard, by contrast, are all about John defying

gravity. Jon surfs the back of a jet

fighter -- standing on two feet -- as it accelerates and spins high in the air.

When at last he is thrown off the jet,

he is flung a great distance, and his bones don’t shatter when he lands.

See

the difference? Here, he is not a man

working with gravity, he is a man somehow defying it…until he doesn’t. Look at

how he drives a several-ton truck up a steep incline, and it doesn’t tumble

down, towards the Earth. At least not immediately.

Here,

it is clear, we have moved into the terrain of outright fantasy. Die Hard becomes a stunt-filled

comic book instead of a film series about a guy who is so stubborn, so thorny

that he will just not give up.

It’s

a huge shift in the paradigm, and one that doesn’t fit well with series

history.

Some

of the outrageous stunts here would be more forgivable, perhaps, if we felt

more in touch with the characters.

Timothy

Olyphant’s character, Thomas Gabriel, is the Marco Rubio of Die

Hard villains. He’s young, he’s attractive, and he’s hip, but…on close

analysis, he’s nothing more than acceptable.

Like

the villains in all the Die Hard movies, Gabriel is supposed

to be a cunning and brilliant thief, who cloaks his venal love of money behind

some act of apparent terrorism, in this case one that reveals to the U.S.

government how vulnerable it is to cyber-attack.

But

ask yourself a question: do you ever once believe that Olyphant’s Gabriel is a

thief? Pulling a con? Does he ever get a

truly memorable scene, or even a memorable line of dialogue?

Mostly,

he’s just a handsome bad guy who fits the template of action movie

villain. Now, this isn’t an attack on

Olyphant, who is a great actor and has delivered remarkable performances in TV

series such as Deadwood (2004-2006) and Justified (2010 – 2015). Even

Olyphant has reported that the character of Gabriel is undeveloped.

Gabriel

looks good, provides some generic menace, but never shows off any real

humanity. The best two villains in the Die Hard series -- played by Alan

Rickman and Jeremy Irons, respectively -- ably convey humanity. We get the sense that they are particularly clever

robbers, ones engineering the greatest cons (and robberies) of all time. There’s no sense of joy or accomplishment

from Gabriel. He’s an off-the-shelf, generic villain to go with the

off-the-shelf, generic action scenes.

I

appreciate aspects of the film. I appreciate that John is now world weary;

beaten down by life. He sees very clearly that fighting bad guys has not made

him happy, or held his family together. He has many regrets. This is all conveyed in a powerful scene, and

the moment demonstrates why Willis is so great for this role. He boasts great range as an actor.

But

that’s the thing. The screenplay must

make use of that range. Not just here or there.

All the time.

We

should be encountering a John McClane who is in danger, on the edge,

half-crazy, running on adrenaline. The

movie rarely uses him in that way. Like

a real person. Like a person we will

wish we could be.

Except

for a flash of humanity here or there, McClane might as well be played by

Schwarzenegger this time out.

So

no, this movie doesn’t “die hard.”

But it doesn’t exactly “live free”

either.

It

lives, instead according to the sanctified rules of homogenized movie-making in

the 21st century. The key rule

of that style of movie-making is: be as broad-based in your appeal as possible,

no matter the subject matter of your film.

It’s

all… “Yippy-kay-yay…you (gender neutral, PG

rated put-down).”

And

that’s a disappointment.

I was skeptical when I went to see this, but I went mainly because parts of the film were shot in my hometown of Baltimore. I walked away enjoying the movie, but feeling like it was something other than a Die Hard movie. Mission: Impossible III had come out the year before, and it reminded me a lot of those Tom Cruise vehicles. You have an underdeveloped hero, and underdeveloped villain, a nerdy tech sidekick for comic relief, and lots of other-the-top action. Great fun, but not Die Hard.

ReplyDelete"Gravity defying" seems to be the defining nature of action in the 21st century. CGI allows filmmakers to create stunts that could never happen in the real world. That's okay in superhero movies, but for characters that are supposed to be rooted in the real world, it's jarring and unsatisfying. At least Tom Cruise actually does some of the crazy stunts for real, but most action films today look no better than Frankie Avalon standing in front of a rear projection rig pretending to surf.