Creator of the award-winning web series, Abnormal Fixation. One of the horror genre's "most widely read critics" (Rue Morgue # 68), "an accomplished film journalist" (Comic Buyer's Guide #1535), and the award-winning author of Horror Films of the 1980s (2007) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002), John Kenneth Muir, presents his blog on film, television and nostalgia, named one of the Top 100 Film Studies Blog on the Net.

Sunday, November 30, 2014

Advert Artwork: The Brady Bunch Fan Club Edition

Labels:

Advert Artwork,

The Brady Bunch

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Amazing Stories: "Lane Change" (January 12, 1987)

In

the second season Amazing Stories (1985 – 1987) episode “Lane Change” by Ali

Marie Matheson, a business-woman, Charlene (Kathy Baker) is driving on a

rain-swept highway alone at night. She picks

up an older stranger (Priscilla Pointer), who needs a lift to the next gas

station.

On

the road together, Charlene and the older woman strike up a conversation, and

talk about the fact that Charlene is leaving her husband George because he didn’t

fight for her when she announced she wanted to leave him.

As they drive and talk, Charlene sees several

strange sights on the road, including her father’s Studebaker, and the car she

and George shared on their honeymoon…

I won't pull my punches: Amazing

Stories is one of the most crushingly disappointing TV series in history.

Perhaps

expectations were too high, given Spielberg’s film pedigree and blockbuster track-record.

Or perhaps the series

simply lacked a cohesive hook, an umbrella of unity like “the Twilight Zone” or

“the Darkside,” which was immediately accessible and understandable to

audiences.

For

whatever reason, some Amazing Stories episodes are just the pits. “Fine Tuning,”

“Hell Toupee,” “Miscalculation,” and “Secret Cinema” are absolutely groan-worthy entries.

Other tales feature a brilliant build-up,

like “The Mission,” but end in ignominy with magical happenings and sharp left

turns into fantasy that negate the sense of reality so arduously-created previously.

Many of the stories seem designed simply to

show off a large budget, but have nothing to say about human nature. The stories aren't amazing so much as thin and two-dimensional.

As a kid in the eighties I watched every episode, at least in the first season, because I kept hoping the series would get something right.

It did, occasionally, like "The Amazing Farnsworth," for certain. But on a weekly basis, Amazing Stories got its clock cleaned by the new Twilight Zone, Tales from the Darkside or even The Hitchhiker.

One

episode that bucks this trend is “Lane Change,” which originally aired on January 12,

1987. The entire episode takes place

in a car, as two women talk to one another, and

discuss life, relationships, missed opportunities, and the future.

The episode has no special effects to speak

of, no tone-shattering lunges towards dumb comedy, and no schmaltzy reaches for

unearned sentimentality.

Instead, "Lane Change" is an economical story about the way that we sometimes let ourselves become

passengers in our own lives, and let someone else do the driving.

Specifically,

Charlene remembers the behavior of her father.

When her mother died when

Charlie was young, the little girl cried on the way home from the funeral. Her

father punished her for showing such weakness, and made her sit in the back of

the aforementioned Studebaker because “babies” sit in the back.

Unwittingly, and perhaps even sub-consciously,

Charlene has grown-up to live her father’s life, Now she is sacrificing her marriage because

she can’t respect a man like George...because he cries.

Subconsciously she has assumed her father's draconian, unemotional world view.

That’s

just a piece of the episode’s puzzle. As

the title indicates, it is possible, while driving, to change

lanes, to pick a new direction. We may

end up at bad places sometimes, but we can always get back out on the highway, take another

turn, and make a better choice.

“Lane

Change,” at its most basic level concerns a woman who averts a bad decision. Charlene changes lanes and arrives at a better destination for herself; a destination promised

by the presence of Priscilla Pointers’ character.

This

episode of Amazing Stories feels a lot like an entry in Rod Serling’s

Twilight Zone (1959 – 1964) and that’s because “Lane Change” remembers that

human beings, not visual effects or gimmicks, make for the best

storytelling.

“Lane Change” is uniformly

well-acted, and rather emotional too. If you’ve

ever let someone else “drive” your decisions -- even unconsciously -- you’ll understand where Charlene

is coming from in this episode. So many Amazing Stories episodes are stylish with no substance...shallow, facile tales that don't amaze in the slightest.

"Lane Change" is an intimate step in the right direction.

Labels:

1980s,

Amazing Stories,

anthology,

Steven Spielberg

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Outré Intro: Amazing Stories (1985 - 1987)

The 1985-1986 television season brought the world the Great Anthology War. It was the year that CBS revived The Twilight Zone, The Ray Bradbury Theater premiered in syndication, and NBC resurrected Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Meanwhile, The Hitchhiker and Tales from the Darkside were already broadcasting their later seasons on HBO and in local syndication, too.

The most ballyhooed anthology of all, however, was Steven Spielberg's Amazing Stories, which aired on Sunday nights at 8:00 pm on NBC, and which was guaranteed for a full two seasons -- a whopping forty-four episodes -- before the first episode even premiered. Each half-hour installment was budgeted at the princely-sum of $800,000 dollars.

Amazing Stories, however, didn't quite live up to the hype.

In fact, I'll never forget my (bitter) disappointment with the series' first few installments. "Ghost Train" was a special effects-laden variation of an old One Step Beyond story called "Goodbye, Grandpa," only re-made to tug at the heart-strings, and "The Mission" -- a claustrophobic, well-shot World War II story set aboard a damaged bomber -- ended with a fantasy cartoon moment out of left field.

Critics didn't hold back.

The New York Times called the series a "spotty skein of cliches, sentimentality and ordinary hokum." Tom Shales termed the Spielberg program "one of the worst ten shows of all time, in any category...over-cute and over-produced...with primitive premises."

And at The New Leader Marvin Kitman coined the series "Appalling Stories."

Despite the bad reviews, however, the opening or introductory montage for Amazing Stories remains absolutely stirring.

Accompanied by a soaring, triumphant John Williams theme song, the introduction dramatizes -- in a short amount of time -- nothing less than the entire history of storytelling.

We begin in prehistory, as a caveman family (no, not Korg 70,000 BC...) sits around a blazing campfire, and a grandfatherly tribe leader dramatically tells a remarkable tale, his loved ones at rapt attention.

As the camera probes closer, we see, in close-up, the man's passion for his stories. At this point in our development, oral storytelling was the mode of communicating and maintaining a common or shared history.

In the next series of images, we move up through the ashes of the tribe's camp-fire, and ascend towards modernity.

First, we see an ancient Egyptian construction, a tomb perhaps, and witness a scroll unfurl, with a story inscribed upon it.

First, we see an ancient Egyptian construction, a tomb perhaps, and witness a scroll unfurl, with a story inscribed upon it.

Next, we move up and forward into the Middle Ages, and a cathedral, where a bound book flies the length of the chamber.

The CGI here may look primitive today, but it still gets the job done. The imagery reminds us of the role that the written word, and storytelling, have played in human civilization across the centuries. In this span, words on a page are a way of maintaining history, and sharing favorite tales.

The CGI here may look primitive today, but it still gets the job done. The imagery reminds us of the role that the written word, and storytelling, have played in human civilization across the centuries. In this span, words on a page are a way of maintaining history, and sharing favorite tales.

Next, the flying book promises stories of horror (represented by a painting of a haunted house) and magic (symbolized by a magician's black hat, and playing cards...).

We're not just countenancing run-of-the-mill stories then, the imagery suggests, but amazing, wondrous ones.

We're not just countenancing run-of-the-mill stories then, the imagery suggests, but amazing, wondrous ones.

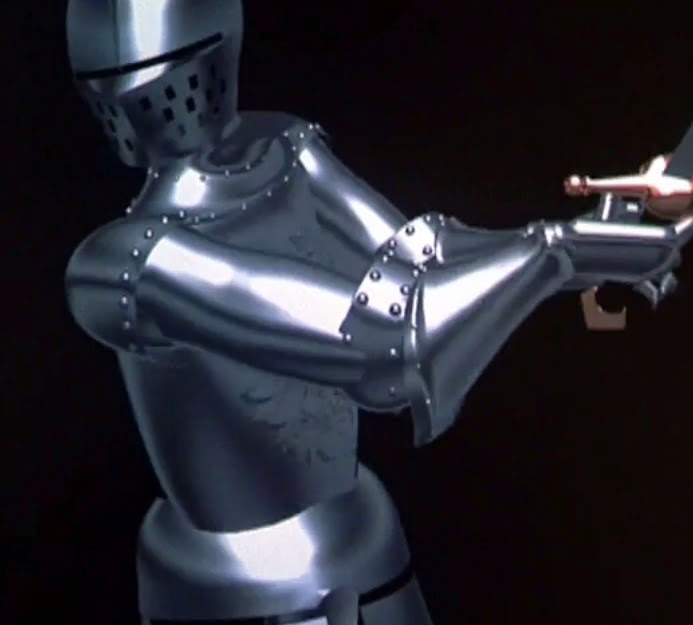

Next, a book is opened, and on the page an illustration of a knight comes to life, suggesting that stories serve a wonderful purpose: They ignite the imagination.

The knight transforms, next, into a spaceship, and so we consider the idea that when we broach the stars in our future, we will continue to tell stories, and take our cherished stories with us.

The spaceship veers off and we turn our attention back to planet Earth. We move toward the planet, and careen down towards a 20th century city in America...

The lights of the city at night become, intriguingly, a circuit-board on a TV or computer, suggesting that in our age, technology -- not the voice of the prehistoric cave leader, or the bound scrolls and books of antiquity -- bring us our favorite tales. Once more, the mode of transmission has been altered, but not man's love of stories and storytelling.

The montage ends with that same cave-man from the opening imagery. Only now, we are watching his story on our TV set, an act which completes the tradition and history of human storytelling. The cave man's story, with us since the very beginning, is now transmitted to millions on television, as a middle-class, 20th century family watches.

Next our series title forms.

Say what you want about the quality of the actual stories depicted on this Steven Spielberg TV series, the introduction remains an inspiration, and a wonderful journey through the history of storytelling.

Perhaps the stories themselves felt so lacking, in part, because this introduction (and John Williams theme...) raised expectations to a near impossible level.

Here's the intro to Amazing Stories in living color:

Labels:

1980s,

Amazing Stories,

Outré Intro,

Steven Spielberg

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Saturday, November 29, 2014

Saturday Morning Cult-TV Blogging: Korg 70,000 BC: "The Running Fight"

In

“The Running Fight,” Bok (Bill Ewing) is bitten by a large spider while out hunting,

and begins to act erratically and violently, threatening the family.

Korg

(Jim Malinda) understands that the spider bite can do “strange things” to men,

and uses himself as a distraction, allowing Bok to hunt him rather than the

family until the venom in Bok’s blood stream weakens.

But

Bok has “super human strength” brought on by the bite, and is the better hunter

of the two brothers…

Penned

by frequent Star Trek (1966 – 1969) author Oliver Crawford (1917 – 2008), “The

Running Fight” is a solid episode of Korg 70,000 BC, except for the

technical matter of a very fake looking spider.

The installment opens in picturesque fashion at Vasquez Rocks, but never

quite recovers from the appearance of the furry, immobile arachnid, which bites

Bok on the face, over his eye. Bok’s

red, swollen face looks much more convincing than the spider itself.

This

is also the first episode, I believe, that has explicitly noted Bok is actually

Korg’s brother, although I suppose it could be surmised from earlier

segments. Clearly, Bok’s importance to

the family -- as brother, uncle, and hunter -- means that he must survive the

crisis more or less intact.

This means

Korg can’t harm him, and must risk being his quarry while he is in a deranged

state. One nice element of this final chase is Korg’s decision to change

directions so that the sun is in Bok’s eyes, slowing hi down during his

pursuit.

Narrator

Meredith notes in this episode that “Neanderthal Man does not venture by himself

except in extraordinary circumstances,” and it’s a sound byte that gets reused

throughout the series.

In terms of the threat of the week,

the furry spiders which live in Vasquez Rocks, Korg 70,000 wasn’t on too fanciful ground.

In 2011,

a prehistoric spider fossil was discovered in Mongolia in 2011.The weird impact

of the spider venom, however, causing Bok to forget his family and act

violently, is all fiction.

Next week: “Magic Claws.”

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Saturday Morning Cult-TV Blogging: BraveStarr: "Who am I?"

In

the

BraveStarr episode “Who am I?,” Tex-Hex’s minion Vipra steals the Lost

Book of the Ancients, and uses its magic spells to embark on a reign of

terror. She manifests giant snakes to

trap Jamie, uses a spell to make herself fly, and renders BraveStarr an amnesiac.

BraveStarr

learns from the Shaman at Star Peak that his memories are still there,” but

they are “locked behind a door” and only he can find the key to unlock them.

Meanwhile,

Vipra attacks Fort Kerium, steals the keys to the city and renders herself both

marshal and mayor of the frontier town.

One of the

great TV clichés is the amnesia story.

Captain

Kirk suffered from amnesia and went native as Kirok in Star Trek’s “The Paradise

Syndrome.” Buffy the Vampire Slayer

suffered amnesia in “Tabula Rasa” and imagined herself a regular girl. Even Superman forget his identity for a spell

in “Panic in the Sky.

BraveStarr takes a stab at the trope this

week, with “Who am I?,” a story that suggests -- in the tradition of the

earlier amnesia tales – that even without memories, we are destined to be true

to our identities.

“Who

am I” is a more action-packed episode than some earlier installments of BraveStarr,

and pits the friendly marshal against the evil Vipra, a powerful villainess

equipped with a spell book of “The Ancients.”

She is virtually invincible with the tome in hand, but BraveStarr

summons his feelings of love and friendship to restore his identity and defeat

her.

What could have made the story feel a little less familiar was more background on the Lost Book of the Ancients. Before it is stolen by Tex Hex and Vipra, it arrives on New Texas in a top-scret space cruiser, under protection from Galaxy soldiers. It is termed "the most dangerous book in all the galaxy."

But why is it being brought to BraveStarr, and who are the Ancients?

Next

week: “The Vigilantes.”

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Friday, November 28, 2014

Godzilla: 1985

Godzilla:

1985, or Return

of Godzilla (1985) is the first and only Godzilla movie I was fortunate

enough to see theatrically before 1998.

The

film showed at the Center Theater in Bloomfield, New Jersey, close to my home

in Glen Ridge, and my best friend Bob and I went to see it together. I don’t believe I liked the film very much at

the time. It seemed cheap and overly-sentimental.

All

I knew was that I really liked Godzilla himself.

Always

did.

I

can write definitively, today -- after a

re-watch and almost three decades

later -- that I admire Godzilla: 1985 and now consider it

to be one of the most underrated films in the entire Godzilla canon. Many

critics and audiences at the time were only able to view the film in terms of its

special effects, which in America were considered primitive.

Like

my teenage self, those critics missed the forest for the trees.

Godzilla:

1985 kicks

off the Heisei period of Godzilla film history, a deliberate un-writing all

Godzilla movies post-1954. And while I

don’t think it was necessary to reboot the franchise quite so aggressively, I

certainly understand the desire to get back to basics, or to tweak beloved

material so it remains current, and vital.

In

terms of metaphor, Godzilla: 1985 works very effectively indeed because it was

produced at a time that might be considered a corollary for the 1950s, the era

that shaped King of Monsters.

In

the eighties, the Cold War was burning hot following the Soviet invasion of

Afghanistan in 1980, and President Reagan was a right-wing hawk who called the

Soviet Union “the Evil Empire” and joked on an open mic about “bombing” Russia

in five minutes.

These

points are important because the fears that had given rise to

Godzilla in the first place were so blatantly rearing their heads again

as the Cold War grew hot. Other genre films from this era including The

Day After (1983), Dreamscape (1984), Testament

(1984) and Threads (1984), and they all obsessed on nuclear war and the

environmental fall-out that would follow.

Accordingly,

Godzilla returns in Godzilla: 1985 to threaten Japan at this important historical

juncture, when nuclear tensions were as high as they had been since the early

1960s and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

A

key character in the film is Japan’s Prime Minister, a man who must balance the

aggression/agendas of the United States and the U.S.S.R. as they pertain to

Japan and its involvement in its own defense.

He must decide if he should stand by a principle -- no nuclear weapons to be used on Japanese soil, ever -- or kowtow

to the demands of international partners.

I

have read that some fans consider Godzilla: 1985 too “political” an

entry in the series because of this plot l, but I believe the Godzilla

films always work best when they play

off of specific real life fears or dreads, and react meaningfully to the

dangers of their era. Godzilla:

1985 certainly qualifies on that front.

Boasting

surprisingly artful compositions and a screenplay that explicitly understands

why Godzilla is “tragic” and “innocent,” but not evil, Godzilla: 1985 is actually

a smart, well-crafted entry in the franchise.

Raymond

Burr returns to his role of Steve Martin from the Americanized film, Godzilla:

King of Monsters, and his character notes trenchantly here that “when mankind falls into conflict with nature,

monsters are born.”

Those

portentous words not only define the spirit and purpose of the kaiju films in

general, they comment on the 1980s Cold War period, a period that threatened to

very quickly spiral out of control if tempers were not controlled.

“One

lizard is down for the count.”

The

great monster Godzilla, not seen in Japan for thirty years, is learned to be near

the beleaguered country once more.

Godzilla attacks a fishing boat, Yahata Maru, and also a Russian

submarine, precipitating a nuclear stand-off between Cold War enemies East and

West.

Armed

with evidence that Godzilla is responsible for the sunken submarine, the

Japanese Prime Minister, Seiki Mitamura (Keiju Kobayashi) announces the truth

to the world. Before long, both the

Americans and the Russians are eager to destroy Godzilla using nuclear weapons,

but Prime Minister Mitamura is unequivocal. There will be no nuclear weapons

used on Japanese soil, no matter Godzilla’s destruction.

After

absorbing the energy from a nuclear reactor, Godzilla lands in Tokyo Bay, and

is confronted by the new military weapon, Super X. The plane’s cadmium missiles

knock Godzilla out, but an accidental detonation high in the atmosphere of a

Russian nuke soon brings him back to life.

While

American Steve Martin (Raymond Burr), the “only

American to survive” the disaster of 1954 consults with the American

military, a scientist in Japan, Dr. Hayashida (Yasuke Natsuki) realizes that Godzilla

-- whose brain is apparently like that of a bird -- responds to bird

calls.

Hayashida plans to lead Godzilla to the lip of a volcano, where controlled explosions

will destroy the ground beneath him, and send the monster careening into the

magma below…

“Sayonara,

sucker…”

In

Godzilla:

1985, Godzilla destroys a Russian nuclear submarine, and tensions

between Cold War enemies escalate. The

Japanese Prime Minister, Mitamura, quickly makes a statement affirming Godzilla’s

responsibility in the matter.

After

doing this -- to defuse nuclear war -- the prime minister, however, must deal

with two nations that want him to act in a specific way. Specifically, the matter of using nuclear

weapons on Japanese soil is raised, and the prime minister expressly forbids

it.

Impressively,

Godzilla:

1985 sets up a nice visual framework here, suggesting the nature of the

pressure the prime minister faces.

In

two separate compositions, we see the fluttering flags of the U.S.S.R. and the

U.S.A. on diplomatic cars as they speed their representatives to a diplomatic conference.

The impression is that these two states are rushing to an answer, but not

really considering the problem. Nationalism is the overriding concern, as

represented by the flags, and the issue is accelerating towards a boiling

point, as represented by the fluttering, wavy flags.

A

few minutes later, Prime Minister Mitamura is lobbied by both an American and

Russian representative at the conference.

The very shots here reveal the kind of pressure he faces. His face is seen in the corner of the frame, edged-out,

virtually, as the representative in question makes his point, literally taking center

stage. Then we see the same shot, but with the other nationalist.

Taken

together, these two compositions suggest that the Japanese official is actually

caught between a rock and a hard place. If he doesn’t satisfy both suitors, as

it were, nuclear war could be the terrifying outcome.

Godzilla:

1985 also

suggests that, born of nuclear or atomic power, Godzilla craves it as a form of nourishment or energy. He absorbs a Japanese nuclear reactor and

goes on his merry way, but the metaphorical implication is that once nuclear

power is used, the door on its use can’t be easily closed.

Godzilla

isn’t a one time “event.”

Instead,

he constantly craves the nourishment that reactors provide, and we can parse

that idea to mean that once we incorporate nuclear energy into our regular

usage patterns, it is impossible to remove it easily.

Godzilla -- and the civilized world – is “addicted”

to the power that nuclear weapons and nuclear energy provide. And nuclear energy is, by its mere nature,

dangerous.

The

nuclear tensions between the Russians and Americans actually strengthen

Godzilla, as we see in the film. A detonation over Tokyo -- caused by the

Soviets -- provides the energy the goliath needs to overcome the cadmium missiles

of Japan’s flying weapon, the Super X.

I

also admire the subplot in Godzilla: 1985, largely brought forward

in the American version by Raymond Burr’s character, Martin. It states, essentially, that to conquer

Godzilla, one must not use weapons of war.

Instead,

one must seek to understand his nature. “He’s looking for something…searching,”

Martin tells the military. “If we can find out what it is before too

late…”

That

line may sound silly in the cold light of day, but it’s an important expression

about understanding – and listening -- to nature.

Although

I am a big fan of the colorful and mostly kid-friendly Godzilla movies of the

1970s, I also admire how Godzilla: 1985 attempts to maintain

the menace and mystery of Godzilla.

Almost

every scene involving the big green lizard is set at night, in darkness. Somehow, under an impenetrable, ebony sky,

Godzilla looks all the more real, and terrifying. His landing in Tokyo Bay is a great set-piece,

and the miniature work of his destructive stomp through the city is a great

improvement over similar scenes in the 1970s.

I

also dig the moment at the reactor when a guard spots Godzilla, and the camera

pans up and up and up and up, to his roaring mouth. This moment does a fine job of suggesting

Godzilla’s sheer size.

Similarly,

there are more moments here than in previous Godzilla films wherein

the camera is tilted up, gazing at the beast from a low angle, thus demonstrating

his massive scale. In many cases,

Godzilla really looks “huge” and not just like a man on a suit, stomping through

a miniature sound-stage. The right angle

and the right point of view matter.

Finally,

Godzilla:

1985 does a terrific job of walking the line about the monster’s

contradictions. Godzilla is a terror, to

be certain, and yet he is also in Martin’s words “strangely innocent and tragic.”

This

description is a knowing and sympathetic way of acknowledging that Godzilla is

both a monster, and, in a weird way, a beloved character to the audience. My biggest complaint about the American Godzilla

(1998) is that it never decides how the audience should feel about the

monster. Should we love him or hate him?

Godzilla:

1985 makes a

choice in that regard, and a good one.

It reminds us that Godzilla is a terrible natural threat -- a hurricane

or a volcano with thunderous thighs, essentially -- but that we can still feel

sorry for him as a living being out of his time, and out of his place. We can have empathy or him, because we made

him what he is…

Labels:

From the Archive,

Godzilla

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

-

Last year at around this time (or a month earlier, perhaps), I posted galleries of cinematic and TV spaceships from the 1970s, 1980s, 1...

-

The robots of the 1950s cinema were generally imposing, huge, terrifying, and of humanoid build. If you encountered these metal men,...

.png)