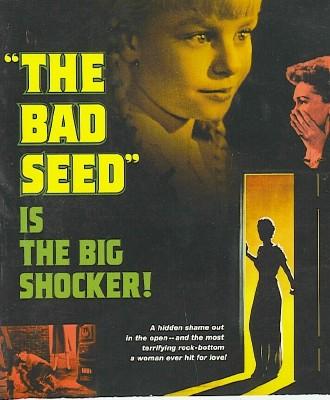

One of the best and most chilling horror films of the 1950s is Mervyn Le Roy's elegantly-directed The Bad Seed, an adaptation of the novel by William March (a best-seller) and the popular Broadway play by Maxwell Anderson. The Bad Seed not only forecasts such landmark films as Hitchcock's Psycho in its depiction of "evil" arising in an unexpected (family) setting, but such popular movies as The Exorcist for its use of a child as the fulcrum of terror.

One of the best and most chilling horror films of the 1950s is Mervyn Le Roy's elegantly-directed The Bad Seed, an adaptation of the novel by William March (a best-seller) and the popular Broadway play by Maxwell Anderson. The Bad Seed not only forecasts such landmark films as Hitchcock's Psycho in its depiction of "evil" arising in an unexpected (family) setting, but such popular movies as The Exorcist for its use of a child as the fulcrum of terror.The Bad Seed dramatizes the tale of young Rhoda Penmark (played with chilling cheeriness by Patty McCormack). This perfectly-dressed, pig-tailed little cherub, along with her doting parents, rents a nice apartment, attends a good school, and apparently comes from good stock...and yet this pre-adolescent girl is nothing less than a sociopath.

In the course of the film (while her absentee military father is away...), Rhoda's mother, Christine (Nancy Kelly) must come to terms with the fact that Rhoda has murdered a little classmate named Claude...all because he beat her out for the school's coveted penmanship medal. Rhoda lies and twists the truth, even when confronted with it by the apartment's not-so-bright handyman, Leroy, and Claude's grieving mother, the drunk "lower class" lady, Mrs. Daigle (Eileen Heckart).

When Leroy dies in a mysterious fire (set by Rhoda...) and Christine discovers the penmanship award hidden away in Rhoda's treasure drawer, Mom is forced to confront the notion that even in a so-called good family, evil can still grow. And the reason for this evil shocks her. For it concerns Nancy's own special heritage, and sparks a heated debate about nature vs. nurture. Is evil encoded in the genes? Or does it arise out of environment? These are the questions The Bad Seed tackles in frightening and memorable fashion.

Today, we still discuss The Bad Seed in regards to children who we think of as really, really "bad;" it's a kind of pop-culture shorthand. There was a 1985 TV remake of the material, and also a 1990s film called The Good Son which made the evil child a boy (played by Macaulay Culkin). Even as I write this, a remake of The Bad Seed is on its way from Hollywood, under the auspices of Cabin Fever director Eli Roth. The reason for the story's longevity? Well, children always represent our tomorrows in horror films, and when children are corrupted, so is our future. Furthermore, on a much more basic level, the idea that something so innocent-appearing could actually be so evil is, I believe, a genuine and universal human fear. Especially if you're a parent.

One of the most illuminating aspects of the film is the manner in which it covers the "nature versus nurture" debate. The movie-going public in the 1950s was becoming more and more cognizant of psychology and the writings of Sigmund Freud, and the prevailing attitude of the era came from a fellow named John Watson. His approach was called "behavioralist," and it emphasized the importance of environmental determinants in shaping human behavior. B.F. Skinner was also a (later) advocate of this notion that external events - environment - dictate the occurrence of certain behaviors. So that's the "nurture" theory.

In the film, Rhoda's grandfather, an erudite crime reporter played by Paul Fix, advocates this theory. To him (and to Skinner and Watson), there's no such thing as a bad seed, or being bad by nature (or what we would say is bad by genetics/heritage.) It's easy to understand why Fix's character might believe this; why he might prefer "the nurture" theory. He is rich, white and privileged, after all. It is convenient and easy for the "upper class" of WASP-y aristocracy to believe that criminals are made, not born. That they come out of poverty; that they come out of lack-of-education; that they come out of poor upbringing. By believing this, you can blame bad acts on people who are less fortunate, and also make excuses for them at the same time. "Oh, they don't go to the right Church." Or those people don't have the "right" values. So make no mistake, The Bad Seed is also about America as a class society; just look at how the "poor" Mrs. Daigle is treated in the film.

But back to the point. The nature versus nurture debate remains one of the enduring controversies in developmental psychology. I believe it was Arthur Jensen who published an article (in the 70s?) arguing the opposite point as Skinner and Watson, that intelligence is largely inheritable. And if that's the case, as human beings we must begin to question - as Christine does in the film - what other traits or qualities are also inheritable? Conscience? Empathy? This is the terrain of The Bad Seed, and Christine comes to realize that her daughter, Rhoda, is not so much evil as she is handicapped. Christine twice makes reference to a sociopath as like a "child being born blind." In other words, a critical human sense is missing from Rhoda, if not eyesight then certainly soul. We don't kill blind children, do we? We don't mistreat the deaf, right? But a child who is a sociopath is a totally different story, because - as Rhoda proves so dramatically- she's dangerous to others. Always.

Because psychology was gaining mainstream acceptance in the 1950s, The Bad Seed is obsessed with the public at large attempting to practice psychology...without a license. The movie seems to be saying "don't try this at home; leave it to the professionals." The landlady character, Monica, is a prime example of this public misunderstanding the core tenets of psychology. She offhandedly states that "analysis" broke up her marriage. More to the point, she's always going around diagnosing - or rather, misdiagnosing - the people around her. She performs Freud's "free association" process like it's some sort of social parlor game, and is ultimately completely clueless about the real nature of those closest to her, particularly Rhoda. It's strongly suggested in the film that Monica herself will be the next victim of the "bad seed" because she had promised Rhoda ownership of her love bird when she dies. So the democratic voice of the people and psychology in the film - Monica - is clueless, helpless, and in fact, endangered.

The critical skinny on The Bad Seed is usually that is a very good, very solid film, but that the very theatrical nature of the drama makes it stagey and even a bit campy by today's standards. It's probably true that some aspects of the film are campy, but I also find it genuinely terrifying. Because the film is based on the play (and features, in fact, the play's cast...) it does come off as a bit stagey at times. The film is very theatrical, yes, I agree. For example, we get a soliloquy from Leroy the gardener at one point, and that's a good stage technique, but an awkward film one. And we don't often leave the apartment interior for the great outdoors, giving the film the feeling of a stage-bound production. Finally, we even get a bizarre, reality-shattering curtain-call at the end of the film to introduce the cast and even make light of the preceding horrors. But like Shakespeare's MacBeth and the murder of King Duncan, notice how much of the important action of the film takes place off-camera. This is intentional. We never actually see Rhoda committing murder, and that's a crucial distinction. The film is much more concerned with how Rhoda covers up, how she appears normal, than with the abnormal and anti-social acts she commits.

What's more frightening, you may ask, than a child committing murder? How about the sight of a cute-as-a-button little girl making excuses, manipulating her parents, and having no sense of morality other than the fact that she wants what she wants? At one point, she coldly tells her Mother that she doesn't feel "any way at all" about the death of little Claude, and how it must make Mrs. Daigle feel. Sheesh. That's more terrifying than a girl pushing a boy into the water. Rhoda believes all along that she is "right," "justified" and "entitled" to do what is best for her, and it's all the more frightening, because the camera focuses on her dissembling and lying more than it visits the exact nature of her crimes. We are confronted with the idea that there exist human beings unable to feel remorse, pity, empathy - anything we remotely recognize as "moral" - and that they're out there; and that they sometimes hide undetected behind pig-tails and smiles. The movie would have gotten lost in psycho-killer cliches had it actually visualized Rhoda committing her "kills."

I submit that the stagey, theatrical approach of The Bad Seed actually works rather well with the material. It's an advantage, not a detriment. There's a palpable sense of claustrophobia to the film (and increasing hysteria, too...) since Christine is our protagonist and she feels helpless to resolve the crisis. Her husband is MIA most of the film, and let's face it, in 1950s Leave it to Beaver America our heroine has few options, and so therefore we stay and we stay and we stay in that damned apartment and our sense of discomfort grows exponentially. Had the film been opened up more, been made more conventionally cinematic, I feel the viewer would have lost the sense of Christine's entrapment with this monster. As it stands, we're right there in that apartment beside her. It would be much harder for us to accept Chrstine going mad at Rhoda's endless repetition of Claire de Lune on the piano if we could easily escape it for a corner cafe, a grocery store, a police station, a school, a church or the like.

The other critical slam against The Bad Seed involves the ending. Don't read any further if you want to be surprised. Okay? Still here? Fine. Here's the deal, the movie changed the play's original ending. In the movie, Rhoda goes to the pier where she killed Claude and tries to fish out her penmanship medal from the water (where her Mom dumped it.) A storm has rolled in, and Rhoda is carrying a big metal net on a stick. Well, she's struck by lightning and that's the end of the Bad Seed. Problem solved.

In the book and the play, things were different. Little Rhoda got away with her crimes, and society was unable to recognize her for what she clearly was, a monster. But, in America in 1956, we had the "The Motion Picture Production Code" to contend with and it stated something along the lines of "crime shall never be presented in such a way to throw sympathy with the criminal against law and order." This edict meant that The Bad Seed could not be dramatized on film as it had been on stage. Rhoda couldn't escape some form of justice.

So the ending of the film had to be altered. Critics complained because they saw the new ending (a lightning strike against Rhoda) as divine intervention, a Deus ex Machina answer. Well, I beg to differ with that assessment. I would argue that the new ending of the film works rather well, and furthermore, that director Le Roy builds it into the film with a sense of grace.

For example, the film opens with a shot of the pier where the murder of Claude (and ultimately, Rhoda's death...) takes place. Off in the horizon, hanging low in the black-and-white sky, we see thunder clouds gathering, and even lightning flares. So we are reminded of "nature" first off in the film, rendering the climax not something out of the blue, but rather a book end: a return-to-nature (and the scene of the crime).

Then, handyman Leroy taunts little Rhoda later in the film. He says that dying in the electric chair is like being "hit by lightning," again foreshadowing Rhoda's particular fate. So when the lightning finally strikes Rhoda, it has been adequately set-up. It's consistent with the opening shot of a storm, and Leroy's foreshadowing.

Also, I would say that any critical analysis of the film must consider that the core conflict of the film is what I discussed above: the nature vs. nurture debate. Rhoda is a "bad seed," a bad person by nature (by her heritage; since her real, biological mother was a murderer...). In the end, it is only correct then that Mother Nature (i.e. the lightning strike), not Mother Nurture (Christine herself) is the one to ultimately deal with Rhoda. This is not divine intervention, this is not God. This is Nature destroying that which is corrupt, that which is wrong. It is nature taking care of its own.

Lasting a mesmerizing 129 minutes, The Bad Seed should be at the top of every horror fan's list of "must see" films. It is a product of its time in that there is very little on-screen violence. It's also a pioneer in the way that it plumbs the depths and breadth of human psychology. In addition to presenting the nature vs. nurture debate in entertaining and provocative terms, I think it's also only fair to state that the movie gives us some of the most chilling dialogue to come out of 1950s horror cinema. You'll definitely catch a case of the chills from Rhoda's constant refrain, "What would you give me for a basket of kisses?", or Monica's unknowing comment to her father, "You still have Rhoda."

Like that is somehow comforting. To quote Leroy the handyman: "I've seen some mean little girls in my time...but you're the meanest."

i saw this movie couple of times between ages 10 and 17. i question my mother's sanity for allowing me to see this. at age 56now, i will not ever watch this again. nor would i have ever allowed my childen. adults now, i would still caution them. this is one freaky movie. the scene where the gardener passes will keep you up nites for days.

ReplyDeleteThis is one of the best, spot on reviews I have read on this movie, and one of the only ones to explain the ending difference with the book. While Nancy Kelly's over the top melodrama and poor timing reminded me of Gracyn Hall from Dark Shadows, it was duly pointed out that she was primarily a stage actress and it was 1956 after all. I agree with many critics that this would make a great remake in capable hands, but this original is a classic in it's own right.

ReplyDeleteYeah...nature for real doesn't work that way actually.

ReplyDelete(The part about Rhoda's death)

Nature isn't conscious of ideas that humans manage to come up with just to deal with threatening people. People who want to kill killers and killers who want to kill people is just another part of the animal kingdom doing it's cycle-of-life thing.

Good review though 0.0/~

The Bad Seed is one of the best Thrillers I have ever seen. It sends chills up your spine when Monica tells Rhoda's Father: "You still have Rhoda!"

ReplyDeleteSPOILER

ReplyDelete"Rhoda is a 'bad seed,' a bad person by nature (by her heritage; since her real, biological mother was a murderer...)."

Great article, but Christine _is_ Rhoda's biological mother; it's Rhoda's grandmother who was a killer.

Most informative piece I've read on one of the most fascinating movies of the era. I agree it is more effective than the kiddie slasher films. Hunting Violets is right about the grandmother being the psycho. The song Rhoda plays is Au Claire de la Lune not Debussey's Claire de Lune.

ReplyDelete