Creator of the award-winning web series, Abnormal Fixation. One of the horror genre's "most widely read critics" (Rue Morgue # 68), "an accomplished film journalist" (Comic Buyer's Guide #1535), and the award-winning author of Horror Films of the 1980s (2007) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002), John Kenneth Muir, presents his blog on film, television and nostalgia, named one of the Top 100 Film Studies Blog on the Net.

Monday, December 12, 2022

50 Years Ago Today: The Poseidon Adventure (1972)

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Sunday, December 11, 2022

40 Years Ago Today: Timerider: The Adventure of Lyle Swann

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Friday, December 09, 2022

20 Years Ago: Star Trek: Nemesis (2002)

People age.

They grow old, they grow apart, and they move on with their lives. Chekov changed jobs for The Motion Picture (1979), took a posting on Reliant in The Wrath of Khan (1982), and Sulu assumed command of the Excelsior in The Undiscovered Country, for example. The universe didn’t remain static, like a TV show...which hopes never to end.

The film’s opening wedding scene -- while generally horrendous in terms of dialogue, tone, editing and overall execution -- reminds us that we have known these characters for fifteen years, and that the times are indeed changing. Riker and Troi are finally getting married, and Riker is headed off to command the Titan…after a decade-and-a-half serving in Picard's shadow. Data is moving up to the role of first officer. Worf is just visiting (conveniently, again…).

Fucking wheels?

Certainly, by the 24th century, cars would be out-of-fashion, and wheels wouldn’t be employed when a hover-craft would so, so this vehicle looks and feels terribly out-of-place in terms of the franchise continuity and history.

The result is that the Argo sticks out like a sore thumb.

Disregarding the Prime Directive entirely, Picard, Data and Worf utilize their advanced phaser technology to fight back, and also deploy their advanced shuttle craft. The scene evokes the Road Warrior (1982) in a kind of bad way, but primarily raises so many questions. Why does Picard ignore the Prime Directive? Why are the inhabitants hostile to our heroes? If Data can scan for positronic life signs, why can’t he also scan for the aliens ahead of time, and avoid contact with them? Why can't the Enterprise just beam everyone (and all the tech...) up quickly, and minimize the cultural interference?

If Shinzon had wanted to bring the Enterprise and Picard to Romulus for peace negotiations, he would have had to merely request Picard and his ship. He is now a recognized Head of State, after all. He can pretty much negotiate with anyone he chooses. Instead, the excuse seems to be that Picard was in the area (Kolarus III), and thus the closest ship available for peace talks. It’s all terribly trite and poorly-written, and worse, unnecessarily trite and poorly-written.

It is set on 24th century Romulus, but doesn't make even a passing comment about Amabassador Spock and his unification movement, which we remember from the series.

In 1982, fans had to wait for two whole years for Spock’s return in The Search for Spock. There was no instant gratification at all in that case. By the end of Nemesis, B4 is already whistling Irving Berlin tunes, and there is no doubt that Data lives. This short-period of mourning manages to take away from Data’s noble sacrifice. We have a replacement right here, for the beloved crew member who died...

This is a strong idea, and one that augments the relationships between the crew. Yet the idea fails somewhat because the film’s form doesn’t reflect the narrative's conclusions about the brothers and sisters "you chose." Nemesis focuses on Picard and Data to the exclusion of almost all other characters. Though Troi gets a larger role than usual here, Riker, Worf, Crusher, and La Forge all feel like after-thoughts. A chubby, Shatner-esque Riker battling the Viceroy mano-e-mano is hardly a substitute for meaningful time spent with the character.

Today, the Next Generation crew is arguably just as beloved as the original crew, and it deserves a proper send-off too. Nemesis just isn’t that movie.

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Monday, December 05, 2022

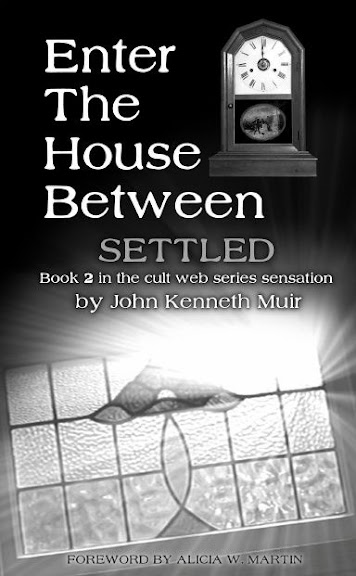

Enter The House Between Novellas #1 and #2 NOW FOR SALE

For longtime fans of this blog and my writing, my 2007-2009 web-series The House Between (which was nominated for Sy-Fy Portal Awards back in the day....), is on the verge of an exciting new re-birth in the weeks and months ahead.

A new audio drama series is due to premiere in Spring of 2023 with original stories (more info to come), and Powys Media is publishing novellas based on the original program as well

The first two novellas, "Arrived" and "Settled" are now available for purchase at the Powys Media web-site!

Now available to order here.

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Saturday, December 03, 2022

MOVIES MADE ME: Book Review: Horror Films of 2000-2009

MOVIES MADE ME: Book Review: Horror Films of 2000-2009:

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Sunday, November 27, 2022

20 Years Ago Today: Solaris (2002)

Yet that’s precisely the case with Steven Soderbergh’s remake of Solaris (2002) starring George Clooney. Although this remake diverges from both the Stanislaw Lem novel and the 1972 Tarkovsky film, the director’s post-millennial iteration of the tale nonetheless succeeds as a consistent and imaginative work of art.

Thematically, Solaris can be interpreted on two tracks.

In the near future, mourning widower and renowned psychologist Chris Kelvin (Clooney) is sent by the DBA Corporation to investigate a dangerous situation on Space Station Prometheus, a facility orbiting the mysterious world called Solaris.

“Are we alive or dead? We don’t have to think like that anymore…”

Unlike the source material created by Stanislaw Lem, the 2002 version of Solaris --- at least from a certain perspective -- offers something of a religious, Christian parable.

|

| The Hand of God |

|

| The Hand of God? |

|

| The Hand of God |

|

| The Hand of God? |

Ensconced in that afterlife, Kelvin soon finds himself back in his apartment on Earth. But he is not alone this time. He is with Rheya…forever. And his guilt over her death is now assuaged. For her part, Rheya informs Chris that this is a place of eternal peace:

At the heart of Solaris is this crucial character, the nihilist, Chris Kelvin. He goes on a mission that makes him re-examine his beliefs and feelings, and runs square up against the human concept of identity. He comes to realize that the Visitor version of “Rheya” is created exclusively from his memory, from his mind.

Or, if one chooses to consider the image symbolically, these composition choices represent Soderbergh’s reminder that even Kelvin – our protagonist – is a man of layers and contradictions. Ultimately, we can’t understand more of his identity than what he reveals to us. This interpretation fits in with the notion I described above, of Kelvin as both firm nihilist/atheist and Kelvin as secret “believer” (or want-to-be-believer, if you will). Can we really know him? Can he really know himself?

|

| What's denied us in this image? |

|

| Trapped in the prison (notice the bars?) of his own beliefs? |

|

| Separated from the world outside. |

|

| Lost in a blur of unimportant faces. |

|

| Finally, Unknowable. |

How can we know anybody, in fact, if “nobody can even agree [about] what’s happening” as one character describes the central mystery in the film. The issue: We are all victims of and slaves to our own unique perspectives.

|

| Who is looking at us from behind those eyes? |

|

| Rheya? |

|

| An imitation? |

|

| Solaris? |

|

| God? |

|

| Forgiveness? |

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

90 Years Ago: Things to Come (February 20, 1936)

One of the pioneering "fathers of science fiction," author H.G. Wells (1866-1946) published a visionary chronicle of the future in...

-

Last year at around this time (or a month earlier, perhaps), I posted galleries of cinematic and TV spaceships from the 1970s, 1980s, 1...

-

The robots of the 1950s cinema were generally imposing, huge, terrifying, and of humanoid build. If you encountered these metal men,...