A

reader, David, writes:

“Here’s an Ask JKM a

Question for you.

All the entertainment

in the world is being systematically destroyed and you get to save only one

episode of Star Trek for future

generations.

Which episode do you

save?”

Yikes!

Now that’s a tough question, David.

I’m

going to narrow it down a little. Since

you didn’t specify any sub-title, I’m going to assume I can only choose an episode

of the original series, not the follow-ups. (If I could pick a Next

Gen episode, it would be “The Inner Light.”)

But

let me walk you through my thought-process in terms of my selection. If only one episode of Star Trek is to survive

for future viewings, I must consider which episode in the canon highlights best

the core elements of the series; which best represents everything Star Trek

stands (or stood…) for.

Some

of my favorite episodes, like “Space Seed,” or “The Trouble with Tribbles”wouldn’t necessarily make the cut. They

are great shows, but I wouldn’t want either to be my representative Trek.

I’d

have to drill-down here a little and answer a key question, I suppose: what does Star Trek

mean to me?

Well,

it’s about friendship. (Kirk, Spock and Bones).

It’s

about the idea of man going out into the unknown and taking his humanity with

him.

It’s

about confronting alien life.

It’s

about learning to see others (aliens, etc.) in a new and different light.

It’s

about resourcefulness on the frontier, on the edge of civilization, when no one

is around to back you up. You have great technology, but that technology is no

guarantee of survival, or victory in battle.

I’ve

been poring over the episode list and I believe have one episode that hits all

those hot spots.

It’s

not my favorite show, though it’s a good one. It’s not even in my top twenty

favorite Treks. (Among my favorites: “This Side of Paradise,” “Amok

Time,” “Metamorphosis,” “Journey to Babel,” “Charlie X,” “The Doomsday Machine,”

and “The Enterprise Incident.”)

But

I would choose “The Corbomite Maneuver.”

This

episode from early in the first season finds the Enterprise encountering a

giant cube in space (no, not the Borg).

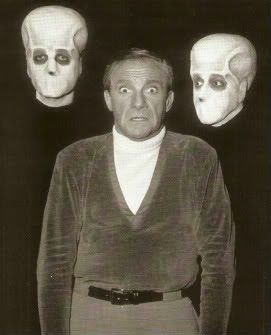

Captain

Kirk reluctantly orders it destroyed when it emits dangerous radiation. Before long, a much larger alien ship -- the

Fesarius -- arrives and threatens the Enterprise. Its captain is the fearsome and very alien

Balok.

Now

Kirk must figure out a way to escape from the technologically-superior ship,

and the merciless Balok.

I

would choose this episode, first, because there’s a clear surrogate for the

audience in the narrative. We meet young

Lt. Bailey (Anthony Call), who is anxious and scared, having never encountered

anything alien. He’s nervous and

burdened by responsibility.

Dr.

McCoy thinks Bailey was promoted (by Kirk) too soon, but Kirk sees something of

himself in the green officer. He sees a man who can learn and grow. This

character -- who voices audience fears and concerns -- helps us to understand

the nature of the Star Trek universe, and the nature of the choices Kirk must

make.

The

episode also features some good back-and-forth in the heroic triumvirate, with

McCoy needling Kirk about his weight, and Spock and Kirk discussing poker and

chess.

Furthermore,

“The Cormobite Maneuver” involves humanity encountering alien life, and not

knowing what to expect from it. In that vacuum, tension rises.

Man brings with

him to the encounter both his inexperience (Bailey) and his experience (Kirk),

which makes for a nice balance, and a nice complete picture of man as a

species.

And

the episode’s finale involves a reveal about the true nature of Balok, and the

way that “fear” is a universal constant. Kirk, Bailey and McCoy board Balok’s ship only to find that the “alien”

is a puppet, and that the real Balok is a child-like alien. He

only presented that other face because he was as fearful as Bailey was about the unknown.

But,

optimistically, this means that man and alien are alike. They feel the same things; they fear the same things. This is a basis for

friendship.

Kirk

is up against the wall in this episode, matched against a superior ship and

superior powers. But he uses a bluff -- from the game of poker -- to find a path to survival. He could easily fail, but he doesn’t.

And when he “wins,” Kirk shows mercy to his

enemy, and curiosity about his enemy too.

This act shows that mankind has truly grown-up. That given the chance, he can choose not to kill,

or hurt another life form.

It

was tough to make this call, but “The Corbomite Maneuver” is representative of Star Trek’s

best ethos, and I think the presence of the rookie, Bailey, makes the episode

easier for newbies to identify with.

I'd love to read choices by readers of the blog...