Creator of the award-winning web series, Abnormal Fixation. One of the horror genre's "most widely read critics" (Rue Morgue # 68), "an accomplished film journalist" (Comic Buyer's Guide #1535), and the award-winning author of Horror Films of the 1980s (2007) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002), John Kenneth Muir, presents his blog on film, television and nostalgia, named one of the Top 100 Film Studies Blog on the Net.

Thursday, December 31, 2009

The Year We Make Contact?

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Wednesday, December 30, 2009

Recapping 2009: Year Four of Reflections on Film and TV

We're rapidly approaching the end of 2009 and -- at least by one way of counting -- the end of the first decade of the 21st century (2000 - 2009) too.

We're rapidly approaching the end of 2009 and -- at least by one way of counting -- the end of the first decade of the 21st century (2000 - 2009) too.Accordingly, I'll be assembling my "best of" lists regarding television and film for 2009, and for the decade too. However, I still have to see Avatar, Moon and Paranormal Activity, so I'm not rushing to judgment here....

But in the meantime I wanted to look back one last time at the year that was, especially here on Reflections on Film and Television. 2009 was the blog's biggest year ever, with a whopping 41,000+ more visitors than in 2008. The last quarter of 2009 was, in fact, the biggest quarter ever on the blog. The year saw approximately 316 posts here, and covered a variety of film and TV-related topics.

Early in the year I looked back at some genre "classics" from my mis-spent youth, including Jaws (1975), Logan's Run (1976), Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), The Black Hole (1979), John Carpenter's The Thing (1982), Tron (1982), Alien Nation (1988), and Enemy Mine (1985).

This year also saw my retrospective of John Carpenter's later career span, including the director's more controversial films: Prince of Darkness (1987), Village of the Damned (1995) and Ghosts of Mars (2001).

A good portion of 2009 was also taken up with my detailed study of the career of another favorite director, the amazing Brian De Palma. I reviewed many of his films including Sisters (1973), Carrie (1976), Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981), Scarface (1983), Body Double (1984), The Untouchables (1987), Raising Cain (1992), Mission: Impossible (1996), Snake Eyes (1998), Mission to Mars (2000) and Redacted (2007).

Early in the year, I also undertook a survey of Jules Verne's Captain Nemo in the cinema, beginning with book and film reviews of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and leading into productions such as Mysterious Island, Captain Nemo and the Underwater City and even the 1978 TV mini-series The Return of Captain Nemo.

In the world of TV, I continued my investigation of the intriguing, thematically-valuable (and consistent) universe of Chris Carter and Ten Thirteen Productions, with two essays on Millennium (Enemies Within, and Snakes in the Grass and Snakes in the Open), as well as a retrospective of the late, lamented Harsh Realm (1999-2000) and "Via Negativa," a late-era X-Files installment starring Robert Patrick. The year ended with a personal and professional high point for me: an in-depth interview with Chris Carter himself.

In other TV-related posts, I dissected the first four episodes of the new V, was underwhelmed by The Vampire Diaries, The Prisoner, as well as the pilot for FlashForward. I also remembered nostalgic cult favorites including Mission: Impossible (1967), The All-New Super Friends (1977), Twin Peaks (1991), Dracula: The Series (1990), Werewolf (1987-1988), At The Movies (1982-1986), One Step Beyond (1959-1961), She-Wolf of London (1991), Automan (1983), The Man From Atlantis (1976), Monster Squad (1976), V: The Series (1986), Firefly (2002) and more.

This was also the year of new cinematic favorites including Knowing, Star Trek, District 9 and Drag Me to Hell. Additionally, 2009 was also the final year of production on my independent, dramatic web series, The House Between (to be released on soundtrack CD and DVD in 2010...). My no-budget but big-hearted show (in the third and final season) was nominated for "Best Web Production" at Airlock Alpha (formerly Sy Fy Portal).

Finally, some of my personal favorite posts this year involved in-depth, lengthy essays. I particularly enjoyed writing The Tao of Michael Myers regarding Halloween (1978), Of Men, Morality and Microwaves (concerning The Virgin Spring and the different versions of Last House on the Left), and Don't Tell Them What You Saw, which concerned the two film versions of Diabolique.

Ahead in 2010, I have two new film books in the pipeline, as well as some other exciting appearances and events coming up. More announcements on all that will follow soon. Here on the blog, I intend to launch another directorial retrospective, and will continue looking back to over 50 years of genre TV programming.

I hope that you'll stick around, and also that 2010 will be as exciting, as fun (and busy...) as 2009 turned out to be in these parts. As always, thank you for reading, thank you for commenting, and thanks for coming back to see what's new. To quote Dirk Diggler, "I'm gonna keep trying if you keep trying..."

Happy New Year!

JKM

Labels:

about John

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

CULT MOVIE REVIEW: District 9 (2009)

In 1915, Franz Kafka's now-famous novella, The Metamorphosis was first published. The narrative revolved around a character named Gregor Samsa -- an average man of little power or influence -- who felt beholden financially to his employer, a sales company called "The Firm."

In 1915, Franz Kafka's now-famous novella, The Metamorphosis was first published. The narrative revolved around a character named Gregor Samsa -- an average man of little power or influence -- who felt beholden financially to his employer, a sales company called "The Firm."Well, powerless Everyman, Gregor Samsa awoke one morning to discover that he had inexplicably transformed into an "insekt." A very large insect...but with human emotions.

Over time, Gregor began to witness his humanity (his language; his appetites; his understanding...) slip away as the insect within took over. Like famous Brundlefly, Kafka's hapless, helpless hero was an insect who dreamed he was a man.

In Kafka's literary work, Gregor Samsa was dismissed and betrayed by his family and completed his transformation to bug (or "vermin") isolated...alone in his room; a dark secret. Finally, his family did away with Gregor all together so it could move on and flourish financially. Economic welfare was prized over loyalty to family. Over human decency itself.

In short, The Metamorphosis was a parable about the human condition as Kafka viewed that condition in the early 20th century; and -- in particular -- one man's place in his nation's economy and power hierarchy.

From stories such as The Metamorphosis (and also from the novel, The Trial), scholars, literary critics and historians have derived the eponym "Kafka-esque."

Today, we all have a pretty good understanding of what that term implies (especially if you've ever stood in line at the DMV...). To be legitimately "Kafka-esque," a work of art must concern the impossibility of individual liberty or freedom inside a bloated State of enormous reach, power and influence. Kafka-esque stories are often surreal and feature bitter ironies (not to mention circular logic, especially on the part of the State's "representatives.") Finally we equate with the term Kafka-esque an impenetrable and inhuman maze of bureaucracy, one from which there is no escape or respite for the individual.

Simply stated, I have never witnessed a more imaginative, more stirring, or more dramatic Kafka-esque vision (and quasi-re-telling of Metamorphosis) than Neil Blomkamp's genre film and parable for our 21st century days, District 9 (2009).

The film concerns the arrival of a massive alien spaceship in Johannesburg, South Africa, and the manner in which the extra terrestrial passengers on that ship -- giant insects called "Prawns" --are quickly marginalized and segregated from the human population in a slum, dubbed District 9.

The film concerns the arrival of a massive alien spaceship in Johannesburg, South Africa, and the manner in which the extra terrestrial passengers on that ship -- giant insects called "Prawns" --are quickly marginalized and segregated from the human population in a slum, dubbed District 9.That district, that ghetto, is to be torn down by global corporation MNU (think Blackwater or Haliburton...) and be replaced by Sanctuary City, a new ghetto that one MNU official readily admits is the equivalent of "a concentration camp."

District 9's central character, a human named Wikus van de Merwe (Sharlto Copley), is a true descendent of Kafka's Gregor Samsa. He is a simple, ultimately powerless man who works for the impersonal -- nay imperial -- corporation, MNU. Van der Merwe has been promoted beyond his competency level (because of cronyism/nepotism) and, on one outing to District 9 to obtain waivers for the Prawn relocation, is exposed to a strange alien "fluid" that begins to transform Wikus --just like his Kafkaesque predecessor -- into a giant insect.

The State, here represented by MNU, comes to consider van de Merwe "The most valuable business artifact on Earth" because his new alien DNA allows him to operate powerful Prawn weaponry. MNU -- commanded by van der Merwe's father-in-law -- wants to take ownership of Wikus and surgically exploit him for his Prawn/human DNA. MNU even concocts the false charge that van der Mewe is a dangerous (and infectious...) sexual deviant...and sells that lie to the gullible mass media to assure that none of van der Merwe's fellow men in Johannesburg will come to the fugitive's rescue.

So, a once "average" man has become prized possession of the State and a scapegoat of the State simultaneously, and what he wants and desires for himself no longer matters. Instead, Wikus finds himself an outcast, one separated from his wife and cut adrift from his fellow humans in the slum of District 9. In the film's haunting final shot, we see the Kafka-esque "metamorphosis" completed, and Wikus is now an overgrown insect fashioning metal flowers out of trash...a haunting reminder of his love for his wife and of his lost humanity.

When I first heard about District 9 last summer, the film's premise sounded to me uncomfortably similar to a movie I reviewed on this blog recently, Alien Nation (1988). In both films, a large extraterrestrial population emigrates to Earth aboard a vast mother ship, is treated with ugly racial prejudice (and given a slang name, whether it be "Slag" or "Prawn.") And in both stories, the aliens are assimilated into indigenous cultures with "human" names, whether it be "Sam Francisco" or "Christopher Johnson." Lastly, both films involve a substance with the capability to mutate DNA: the dangerous drug of the Newcomers in Alien Nation and the Prawn fluid in District 9.

Yet about half-way through my viewing of District 9, I understood that Blomkamp's film actually has far more in common with another celebrated sci-fi movie of the 1980s: RoboCop (1987). You may recall that RoboCop was actually a blistering satire of the Reagan Era, not merely an action film. The Verhoeven film depicted a future United States in which Big Business called all the shots; in which the mass media was insipid to the point of lunacy, and in which every public institution -- even police departments -- had been "privatized" to be run as a business (for profit). RoboCop was a nightmare vision of Reagan's laissez-faire dogma run amuck, extrapolated into the near-future. Why, RoboCop even featured gas-guzzling, over-sized vehicles the likes of which we've all seen! They weren't called SUVs though; they were SUXs. But the point, oddly enough, was that a machine -- RoboCop himself -- was more human than the corporations and avaricious, backstabbing executives of his world.

What I mean to suggest here is that the makers of RoboCop in 1987 gazed at the world around them and made -- admittedly from a standard action formula -- a parable that critiqued the American culture on virtually every front imaginable. Far from being a slavish copy of Alien Nation, District 9 undertakes the same difficult task, only for us, here...now. For the first decade of the twenty-first century, just ending. Careful writers and critics have noted the many similarities between the film's District 9 slum and Capetown during the Apartheid era, but the film's critique goes much deeper, even, than that specific historical context. The critique is...global.

For instance, District 9 aggressively takes on corporate cronyism. As I noted above, Wikus is not really competent to be dealing with alien life forms; but rather was hired because of family ties, and does a "heck of a job," just like poor old Brownie did after Katrina in 2005.

The State, here represented by MNU, comes to consider van de Merwe "The most valuable business artifact on Earth" because his new alien DNA allows him to operate powerful Prawn weaponry. MNU -- commanded by van der Merwe's father-in-law -- wants to take ownership of Wikus and surgically exploit him for his Prawn/human DNA. MNU even concocts the false charge that van der Mewe is a dangerous (and infectious...) sexual deviant...and sells that lie to the gullible mass media to assure that none of van der Merwe's fellow men in Johannesburg will come to the fugitive's rescue.

So, a once "average" man has become prized possession of the State and a scapegoat of the State simultaneously, and what he wants and desires for himself no longer matters. Instead, Wikus finds himself an outcast, one separated from his wife and cut adrift from his fellow humans in the slum of District 9. In the film's haunting final shot, we see the Kafka-esque "metamorphosis" completed, and Wikus is now an overgrown insect fashioning metal flowers out of trash...a haunting reminder of his love for his wife and of his lost humanity.

When I first heard about District 9 last summer, the film's premise sounded to me uncomfortably similar to a movie I reviewed on this blog recently, Alien Nation (1988). In both films, a large extraterrestrial population emigrates to Earth aboard a vast mother ship, is treated with ugly racial prejudice (and given a slang name, whether it be "Slag" or "Prawn.") And in both stories, the aliens are assimilated into indigenous cultures with "human" names, whether it be "Sam Francisco" or "Christopher Johnson." Lastly, both films involve a substance with the capability to mutate DNA: the dangerous drug of the Newcomers in Alien Nation and the Prawn fluid in District 9.

Yet about half-way through my viewing of District 9, I understood that Blomkamp's film actually has far more in common with another celebrated sci-fi movie of the 1980s: RoboCop (1987). You may recall that RoboCop was actually a blistering satire of the Reagan Era, not merely an action film. The Verhoeven film depicted a future United States in which Big Business called all the shots; in which the mass media was insipid to the point of lunacy, and in which every public institution -- even police departments -- had been "privatized" to be run as a business (for profit). RoboCop was a nightmare vision of Reagan's laissez-faire dogma run amuck, extrapolated into the near-future. Why, RoboCop even featured gas-guzzling, over-sized vehicles the likes of which we've all seen! They weren't called SUVs though; they were SUXs. But the point, oddly enough, was that a machine -- RoboCop himself -- was more human than the corporations and avaricious, backstabbing executives of his world.

What I mean to suggest here is that the makers of RoboCop in 1987 gazed at the world around them and made -- admittedly from a standard action formula -- a parable that critiqued the American culture on virtually every front imaginable. Far from being a slavish copy of Alien Nation, District 9 undertakes the same difficult task, only for us, here...now. For the first decade of the twenty-first century, just ending. Careful writers and critics have noted the many similarities between the film's District 9 slum and Capetown during the Apartheid era, but the film's critique goes much deeper, even, than that specific historical context. The critique is...global.

For instance, District 9 aggressively takes on corporate cronyism. As I noted above, Wikus is not really competent to be dealing with alien life forms; but rather was hired because of family ties, and does a "heck of a job," just like poor old Brownie did after Katrina in 2005.

Racism is also a major issue. The Prawns are essentially termed lazy by employees at MNU. We are actually told they possess "no initiative," a common (and racist) refrain against Africans and African-Americans. Accordingly, humans treat the aliens shabbily, allowing them to be exploited by Nigerian profiteers who sell food (cat food...) to them at exorbitant prices. Even Prawn children are deemed less worthy than human children, and there is a disturbing scene in the film during which Wikus and his MNU team thoughtlessly (and with great amusement...) knowingly abort several Prawn hatchlings. Because the Prawns aren't human in appearance (read: non-white;), it is easier to disregard and destroy them.

District 9 also takes on the corporate media and the abundantly false memes it often pushes at the expense of truth. Specifically, the JHB Network terms Wikus a sex criminal, and a firefight in District 9 miraculously becomes "a terrorist bombing!" In real life, we've had reports of death panels, FEMA camps, terrorist fist bumps, the War on Christmas, the trenchcoat mafia, "she said yes!"(Cassie Bernall) and other proven falsehoods propagated on 24-hour news channels without a lot by way of official retraction. Why this week, Mary Matalin went on TV and said that George Bush inherited the 9/11 attacks from Bill Clinton, when in reality the attacks occured after Bush had been Commander-in-Chief for more than eight months. The media's mission in many such instances: to frighten us; to tell us who are "enemies" are so we can fear them. So we can destroy them (and then take their resources with impunity and not feel bad about it...)

We also get commentary in District 9 about the questionable policy of governments outsourcing military jobs to corporations and private security firms (again, think about unaccountable Blackwater and the company's history of abuse in the occupation of Iraq). Many Americans believe Blackwater was forced out of Iraq following a massacre of 17 Iraqi civilians in Baghdad's Nisour Square in 2007. Guess what? Blackwater just changed names to Xe Services and is still operating there. In District 9, MNU is the iron-hand forcing segregation, relocation, genocide...and secret weapons research.

And of course, there is commentary on absurd bureaucracy in Blomkamp'sfilm as well: Wikus must acquire Prawn signatures before evicting the aliens from District 9, a ridiculous notion given that the Prawns are incredibly strong, nine-foot-tall insectoids. Basically, he's asking creatures from another planet permission to put them in concentration camps. It is patently absurd. And, in the tradition of Kafka, utterly surreal.

A blazing, incendiary film, District 9 takes a long hard look at the world we've built in the new millennium and concludes that it is, finally, in the truest sense...Kafkaesque. Wikus -- who was no more than an insect to MNU to begin with -- literally transforms into an insect. Our species, the film seems to acknowledge, has truly jumped the shark.

Accordingly, District 9 implicitly asks the question: how can we expect humans to be decent to aliens when humans are so rotten to each other? When they keep their neighbor's children starving? When they send businesses to foreign lands to exploit resources? When the truth is lost and partisanship and "spin" replaces it? When the bottom line is more important than morality? Make no mistake, District 9 concerns segregation and the circumstances in South Africa in the 1980s, but the film is also about much more than that: it is a universal critique of humanity on the precipice; of global humanity as it exists today.

By pointed contrast -- as we see -- the Prawns at least seem to believe in traditional "human" virtues such as family...and loyalty. Even patience, actually. Christopher Johnson loves his young son and has toiled for twenty years to escape the slum in District 9 by repairing a buried spaceship. When he learns that his people are being subjected to Nazi-like medical experiments by MNU, Christopher's first thought is to bring help; of saving his people. Wikus's first thought when transformed into an insect is for himself: for getting cured so he can resume his life. And when Wikus seems to finally develop loyalty for Christopher Johnson and his son, we must ask an important question: is it because his humanity has vanished? Is it because he has become more "Prawn" now -- and thus more noble -- than man?

In terms of visuals, District 9 is a highly dynamic film. The aliens aren't what I could "realistic," per se (kind of hoary in concept, actually...), but how they appear in the frame, in the compositions themselves, is incredibly realistic. The camera doesn't make a big deal of the Prawns; doesn't focus on them, or even center them.

In terms of visuals, District 9 is a highly dynamic film. The aliens aren't what I could "realistic," per se (kind of hoary in concept, actually...), but how they appear in the frame, in the compositions themselves, is incredibly realistic. The camera doesn't make a big deal of the Prawns; doesn't focus on them, or even center them.Instead, the aliens appear in the background of shots; in a soup line behind the main character, for instance; almost as part of the landscape itself. The effect is stunning; our eyes take the creatures for completely "real." I haven't seen Avatar yet, but I can state with confidence that the visual integration of the Prawns into the real life (live action...) settings of District 9 is jaw-dropping.

I also enjoyed the fact that director Blomkamp encodes his critique of modern, globalized humanity in many of the visuals he crafts. For instance, during a military raid by MNU, Blomkamp cuts to a "gun cam," a first-person-shooter-style perspective that closely resembles contemporary video games like Call to Duty: Modern Warfare 2. That's what this raid really is to the hired guns of MNU: a game in which they get to kill Prawns. One character (the villain of the piece) even rants about how he loves to kill Prawns, and the video-game-style action sequences reflect this lack of humanity on the part of the soldiers.

The mockumentary approach utilized often by District 9 -- consisting of "B-roll" footage of interviewees, fake archive footage of the mothership's arrival 20 years earlier, and "live" newsfeeds --

also contributes to the film's critique of modern man. We know what is happening to Wikus; even as interviewees make blatantly false statements, or news feeds pop-up with BREAKING NEWS ALERTS of the most dramatic (and incorrect) variety.

also contributes to the film's critique of modern man. We know what is happening to Wikus; even as interviewees make blatantly false statements, or news feeds pop-up with BREAKING NEWS ALERTS of the most dramatic (and incorrect) variety.In some corners, District 9 has been criticized because of the film's final act. Basically, the climax involves a sustained (and dramatic) shoot-out between Wikus (in an armed, Prawn robot suit...) and the forces of MNU. The problem, according to some reviewers, is that all of the interesting satire and social commentary goes away, and the film degenerates into mere "action."

Personally, I didn't feel this was the case, and I can point precisely to the reason why: emotional investment. By the time of the final, lengthy gun battle in District 9, I felt heavily invested in the survival of Christopher Johnson and his son. The gunfight was about their survival; about their escape, and -- at least for me -- there was real suspense in that equation. Up to that point, District 9 had been so hardcore, so viciously true to its critiques of human nature, that I expected something terrible to happen. And in the vicious gunfight -- where Prawns are just inhuman targets to be blown apart -- tragedy was certainly a possibility. And the final shots of the film: involving Wikus and the metal/trash flower sculpture, are positively lyrical (and on point, thematically).

Way back in 1915, Franz Kafka worried about how the individual could possibly survive -- let alone flourish -- within an aggressive, overreaching establishment. He feared governments, judiciaries, and yes, corporations. District 9 is a clever realization and updating of Kafka's vision; one created with the very symbols Kafka himself deployed (particularly the metamorphosis of man into insect...). The result is a film that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with genre landrmarks such as Planet of the Apes (1968) and RoboCop (1987). All these films (popular entertainments, miraculously...) hold up a mirror to the audience. All of them ask us to look at the world we've made; and what might become of that world if we don't change trajectory. District 9 is pretty hard on the human race (but then, Planet of the Apes didn't exactly let us off the hook, either...) but maybe Blomkamp's film also serves as a wake-up call.

Are you a man? Or just a bug underfoot, ready to be stamped out by agendas much larger than your own?

Labels:

2000s,

cult movie review

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Friday, December 25, 2009

Happy Holidays!

To all my readers and friends,

I hope each and every one of you has a joyous and safe holiday. If you're out there driving -- be safe. If you're inside over-eating, or discussing politics -- be safe.

I hope each and every one of you has a joyous and safe holiday. If you're out there driving -- be safe. If you're inside over-eating, or discussing politics -- be safe.

Have a great time with your families; and may Santa be good to you...

Warmest wishes,

JKM

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

CULT TV FLASHBACK #96: Mission: Impossible: "The Seal" (1967)

Although this Bruce Geller series is mostly devoid of character development (at least as it is understood in today's television milieu), Mission: Impossible (1966-1973) nonetheless remains one of the most dynamically visual TV series ever created.

Although this Bruce Geller series is mostly devoid of character development (at least as it is understood in today's television milieu), Mission: Impossible (1966-1973) nonetheless remains one of the most dynamically visual TV series ever created.Not only that, but many episodes of the espionage classic are damn near perfectly-executed in terms of generating suspense and thrills.

One good example of this "perfection" is the second season episode, "The Seal," which aired originally in 1967. IMF leader Jim Phelps (Peter Graves) is assigned another crazy mission by his unseen government superior. As usual, if he, or any of his IMF Team "are "caught or killed, the Secretary will disavow any knowledge of his action."

The mission: arrogant American Industrialist J. Richard Taggart (Darren McGavin) has unscrupulously purchased the highly-prized "Jade Seal" statue, the mascot of the small but strategically-vital nation Kuala Rokat, on the Chinese/Indian border. This "priceless, 2000-year old statue" must be returned to the country, or the American government feels the small nation could be driven "into the communist camp."

With Cinnamon Carter (Barbara Bain), Barney Collier (Greg Morris), Willy Armitage (Peter Lupus), Rollin Hand (Martin Landau) and a cat named Rusty (!) as his partners in crime on this impossible mission, Jim sets out to recover the the Jade Seal from Taggart.

But it isn't going to be easy.

The Jade Seal has been locked up in Taggart's personal gallery, which is equipped with a "sonic alarm system," not to mention a pressure-alarm system in the floor, calculated to be tripped at any weight over four ounces. And the doors leading to the gallery are electrified. 500 volts.

Negotiation is out of the picture, naturally. Tagga

rt is a smarmy, self-important bastard. He arrogantly recounts the entire history of the Jade Seal. It was once owned by both Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan, and now Taggart likes that he's in the same club at those hisotrical figures. He openly acknowledges that the item was probably stolen, but all that matters to him is that he purchased it legally. He even ignores pleas from the State Department that he return the Jade Seal. "It happens to belong to whoever happens to have it," he says, calling the treasure "fair game."

rt is a smarmy, self-important bastard. He arrogantly recounts the entire history of the Jade Seal. It was once owned by both Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan, and now Taggart likes that he's in the same club at those hisotrical figures. He openly acknowledges that the item was probably stolen, but all that matters to him is that he purchased it legally. He even ignores pleas from the State Department that he return the Jade Seal. "It happens to belong to whoever happens to have it," he says, calling the treasure "fair game."And then Taggart really lays down the gauntlet. "If someone can steal it from me, it's theirs," he tells Cinnamon, who is masquerading as a newswoman, Mrs. Burton. "If they can steal it from me..."

The remainder of the episode involves an absolutely-inspired, complex strategy to retrieve that statue. The plot involves disguises, magnets, drills, personal trickery (Rollin's expertise; masquerading as an expert in comparative religions and a possible psychic...), and -- of course -- Rusty the Cat.

Rusty's part of the operation is particularly hair-raising. The feline must traverse a narrow bridge -- suspended from wall-to-wall in the gallery -- then open the Jade Seal's glass case. Finally, at Barney's coaching, Rusty must fetch the item (in his mouth...) and bring it back to Jim and Barney.

This scene with the cute orange tabby

cat playing fetch with a 2000-year old treasure -- with life and limb in the balance for the IMF team -- is truly something of a masterpiece of suspense. The cat pauses on the bridge. It drops the Seal at one point. Then it picks it up. We watch the cat navigate the narrow bridge in extreme close-up; each footfall a nail-biter. The progress of the cat is inter-cut with close-ups of Jim and Barney as they perspire. Profusely.

cat playing fetch with a 2000-year old treasure -- with life and limb in the balance for the IMF team -- is truly something of a masterpiece of suspense. The cat pauses on the bridge. It drops the Seal at one point. Then it picks it up. We watch the cat navigate the narrow bridge in extreme close-up; each footfall a nail-biter. The progress of the cat is inter-cut with close-ups of Jim and Barney as they perspire. Profusely.The cat causes other problems too. The whole mission almost goes awry when Rusty breaks out of Jim's grasp and, unnoticed, makes a dash for the aquarium housing Taggart's prized fish. The fish begin to get jittery at the cat's proximity, and soon Taggart is paying attention to the fish, when his focus should be elsewhere if the con is to work. Cinnamon sweeps in, just in time...

"The Seal" finds Mission: Impossible in fine, unimpeachable form. The camera prowls, pans, tracks, zooms (and even acquires objects through the filter of the aquarium for a time...). Impressively, there's a minimum of dialogue (and explanation) to accompany what's happening on-screen. Instead, screenwriters William Reed Woodfield and Allan Balter, along with director Alexander Singer, trust the audience to keep up. Meanwhile, Lalo Schifrin's score creates mood, and serves as a drum-line beat right into your

pulse.

pulse.One impressive sequence -- employing only extreme close-ups -- reveals Cinnamon (face only...) utilizing non-verbal, physical gestures (extremely small gestures, actually...) to relate critical and specific information to Rollin in real-time, as he pretends to be psychic. She does so right under Taggart's nose, and it's masterful.

I also love the "tech" in Mission: Impossible. It's all 1960s, space-race-style futurism. You know what I mean: computer punch cards and over-sized reel-to-reel computers. In fact, one computer in "The Seal" is so large that Barney and Rusty hide inside it for a while. But the focus on the technology -- and also on good old-fashioned American know-how and ingenuity-- recalls an age of optimism when we believed we could achieve anything, and more so, that we were the good guys.

"The Seal" features so many great moments,

it's tough to enunciate them all. Barbara Bain (who won three consecutive Emmy awards for her performances on Mission: Impossible) is absolutely terrific here, feigning innocence throughout the con, and then delivering a final, derisive facial expression that serves as the episode's emotional punctuation. She delivers that metaphorical death blow to Taggart, saunters out a door (accompanied by Schifrin's theme...) and if you don't get goosebumps at the sight of this mission accomplished -- in such style -- you should go see a physician.

it's tough to enunciate them all. Barbara Bain (who won three consecutive Emmy awards for her performances on Mission: Impossible) is absolutely terrific here, feigning innocence throughout the con, and then delivering a final, derisive facial expression that serves as the episode's emotional punctuation. She delivers that metaphorical death blow to Taggart, saunters out a door (accompanied by Schifrin's theme...) and if you don't get goosebumps at the sight of this mission accomplished -- in such style -- you should go see a physician.A boastful villain (courtesy of the charismatic McGavin), a brilliant "con," some terrific camera-work; and at least two scenes of jaw-dropping suspense (particularly in regards to herding that damn cat...): These are the elements that make "The Seal" an impeccable installment of Mission: Impossible.

If you love a good caper, this is one TV show that will keep you literally on the edge of your seat for 50 minutes. Rather than self-destructing (like Jim's instruction cassette), Mission: Impossible has survived for forty years by being damn ingenious.

Labels:

1960s,

cult tv flashback,

Mission: Impossible

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

BOOK REVIEW: The Christmas TV Companion (2009)

So, for a while now I'd been contemplating a blog post here about all the sci-fi and horror television episodes over the years that involve the holiday and holiday season. Then I received in the mail a fun book on that very topic entitled The Christmas TV Companion: A Guide to Cult Classics, Strange Specials and Outrageous Oddities by Joanna Wilson. I realized that someone else had already done all the hard work, so why re-invent the wheel?

Available from 1701 Press, The Christmas TV Companion is a dedicated survey of Christmas TV specials and episodes across the decades, and the book features chapters on both Christmas horror ("Have Yourself an Eerie Little Christmas") and Christmas sci-fi ("Christmas Stars and Men From Mars").

In the horror section, author Wilson digs pretty deep, remembering a 1949 made-for-TV production hosted by the late, great Vincent Price, Charles Dickens' The Christmas Carol. She also discusses one of my all-time favorite Night Gallery installments, "Silent Snow, Secret Snow," and remembers prominent X-Files ("How the Ghosts Stole Christmas") and Buffy the Vampire Slayer ("Amends") episodes. My only disappointment here: no mention of the outstanding (and really, really emotional...) Millennium Christmas episode: "Midnight of the Century." On the plus side, Wilson does feature some words on another Millennium holiday segment, "Omerta."

In the science fiction category, Wilson starts with the most notorious production of the lot: The Star Wars Holiday Special of 1978, set on the planet Kashyyk. Wilson is commendably even-handed and balanced in her criticism of this George Lucas show. She notes that it was our first introduction to Boba Fett, for instance, even if the low quality of the show was "a disappointing shock." In the rest of this chapter, the author remembers ALF ("Oh Tannerbaum!"), Mork and Mindy ("Mork's First Christmas") and Doctor Who's 2005 "The Christmas Invasion."

Additional chapters gaze at Variety Shows and animation (including South Park...), and there's even a chapter on "dark" Christmas specials. Here, Wilson discusses Peace on Earth (1939), a "stunning antiwar MGM Cartoon in technicolor" from animator Hugh Harmon.

A fun and fast read, The Christmas TV Companion is a good recap of Christmas television over the years. It's clear the author boasts a real passion for the topic, and has researched it thoroughly. The book brings up some great (and some terrible...) holiday-themed TV memories. After reading it -- or just flipping through - you'll want to make a beeline to your VHS collection (or DVDs...) to catch the holiday mood with Frank Black, Angel, Mulder and Scully, Alfred Hitchcock, or even the cast of Supernatural. This author is currently working on a Christmas-themed TV/film encyclopedia, and the Christmas TV Companion just whet my appetite...

Available from 1701 Press, The Christmas TV Companion is a dedicated survey of Christmas TV specials and episodes across the decades, and the book features chapters on both Christmas horror ("Have Yourself an Eerie Little Christmas") and Christmas sci-fi ("Christmas Stars and Men From Mars").

In the horror section, author Wilson digs pretty deep, remembering a 1949 made-for-TV production hosted by the late, great Vincent Price, Charles Dickens' The Christmas Carol. She also discusses one of my all-time favorite Night Gallery installments, "Silent Snow, Secret Snow," and remembers prominent X-Files ("How the Ghosts Stole Christmas") and Buffy the Vampire Slayer ("Amends") episodes. My only disappointment here: no mention of the outstanding (and really, really emotional...) Millennium Christmas episode: "Midnight of the Century." On the plus side, Wilson does feature some words on another Millennium holiday segment, "Omerta."

In the science fiction category, Wilson starts with the most notorious production of the lot: The Star Wars Holiday Special of 1978, set on the planet Kashyyk. Wilson is commendably even-handed and balanced in her criticism of this George Lucas show. She notes that it was our first introduction to Boba Fett, for instance, even if the low quality of the show was "a disappointing shock." In the rest of this chapter, the author remembers ALF ("Oh Tannerbaum!"), Mork and Mindy ("Mork's First Christmas") and Doctor Who's 2005 "The Christmas Invasion."

Additional chapters gaze at Variety Shows and animation (including South Park...), and there's even a chapter on "dark" Christmas specials. Here, Wilson discusses Peace on Earth (1939), a "stunning antiwar MGM Cartoon in technicolor" from animator Hugh Harmon.

A fun and fast read, The Christmas TV Companion is a good recap of Christmas television over the years. It's clear the author boasts a real passion for the topic, and has researched it thoroughly. The book brings up some great (and some terrible...) holiday-themed TV memories. After reading it -- or just flipping through - you'll want to make a beeline to your VHS collection (or DVDs...) to catch the holiday mood with Frank Black, Angel, Mulder and Scully, Alfred Hitchcock, or even the cast of Supernatural. This author is currently working on a Christmas-themed TV/film encyclopedia, and the Christmas TV Companion just whet my appetite...

Labels:

book review

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Monday, December 21, 2009

30 Years Ago Today: Where Every Journey Ended; This One Began...

On December 21st, 1979, Walt Disney's The Black Hole was released theatrically in the United States. Critics immediately disliked it, for the most part, and the 25-million dollar space epic was considered a box office bomb.

Yet a generation of kids (this one included) grew up with the film...and never forgot it. Disney's first "PG" rated movie, The Black Hole was an one-of-a-kind combination of disparate styles and moods. It was a swashbuckling space adventure in the mold of Star Wars (1977), down to two cute robots (V.I.N.Cent and Old B.O.B) and mock heroics, but it was also oddly -- and thoroughly -- dark. Creepy even.

On an Earth spaceship in a dark corner of the universe, a mad Captain Nemo-type, Reinhardt, had transformed his human crew into drones; into slaves. He controlled his vast, cathedral-like ship via the massive, red robotic terror, Maximillian (who was equipped with propeller blades as a weapon and wasn't afraid to use them). At one point, Reinhardt even cryptically begged "save me from Maximillian..."

And the film's startling, do-or-die conclusion was a literal odyssey through Hell. Another of The Black Hole's unforgettable images: Reinhardt shunted inside the beast, Maximillian; his desperate human eyes entrapped inside a robotic shell.

Itself inspired by 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, The Black Hole seems to have been the inspiration for films such modern efforts as Event Horizon (1997). And, of course, we're due for a remake in the years ahead; though I doubt a new film can capture the pure, unique creepiness of the original. Hopefully, it can improve some of the film's dopier scientific flaws and dialogue.

In terms of look, The Black Hole was also something special. Outer space itself looked different (bluer...); the spaceship Cygnus resembled a vast haunted house; and the goose-stepping robots had a menacing but realistic air about them. Thematically, the film concerned how humans (and robots) faced the specter of the unknown: with madness (Reinhardt); with cowardice (Harry Booth); with blind devotion (Durant) and - thankfully - with heroism (Holland and the others). This was not an unimportant thing, since beyond the black hole laid a Manichean afterlife of sorts; a binary choice of Heaven or Hell for all souls going beyond the event horizon.

I can't believe it's been thirty years since I first saw The Black Hole. I was in the fourth grade...and I was stunned (especially by the violent death of Dr. Durant). Time flies. Anyway, here's a snippet of my detailed review of the film, from earlier this year:

...in The Black Hole, viewers can detect a number of Manichean ideas expressed in the dramatis personae and the narrative situations. This is especially so during the metaphysical journey through the black hole in the finale, a strange religious twist on the trippy denouement of Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Mani believed that Evil had many faces...but that at all those faces were part and parcel of the same Evil, not different ones.

In The Black Hole, we see Maximillian and Hans Reinhardt as two faces of Evil (mechanical and human, respectively) and in their nightmarish last scene, these two evils literally join to become one: Reinhardt is subsumed inside the robot demon Maximillian. Hauntingly, we see Reinhardt's frightened human eyes peering out from the machine's mechanical shell. This is our last close-up view of the characters, of twin evils welded together.

This strange inhuman union occurs inside the black hole, in a realm that resembles a Boschean vision of Hell, with hopeless souls (the spirit-less humanoids) trudging across a Tartarus-like underworld of sorts as flames lick at the bottom of the frame. High atop a hellish, craggy mountain, the Maximillian/Reinhardt Hybrid rules, like Milton's Lucifer. In keeping with Manichean beliefs, this is visibly the realm of physical things: bodies, mountains, fire...materialism. It is no coincidence either that the production design of the film has colored Maximillian, Dr. Hans Reinhardt and Hell itself in crimson tones. This bond of red -- whether Reinhardt's uniform, Maximillian's coat of paint, or the strange illuminating light of Hell itself -- connects all of them as "the One Evil," not separate evils, conceived by the ancient philosophy.

Contrarily, the four survivors of the Palomino expedition (Holland, McCrae, Pizer and V.I.N.C.ent) find not Hell in at the event horizon, but rather a celestial cathedral of sorts. Their vessel, the probe ship, is guided through this realm of the spirit (not the body), by another soul...a white guardian angel of sorts. The protagonists temporarily seem to exit the world of the body, and the film reveals their thoughts -- past and present -- "merging" during a brief, strange scene involving slow-motion photography.

What this scene appears to portend is that the three humans -- and robot (!) -- have been judged by the cosmic, Manichean forces inside the black hole and found to be above "sin," hence their journey through the long, Near Death Experience-style "light at the end of the tunnel" and subsequent safe re-emergence back into space. Instead of remaining trapped in a physical Hell (like the Reinhardt/Maximillian hybrid), the probe ship and those aboard pass through the gauntlet of "spirituality" where nothing -- not even sin -- can escape, and arrive safely in what appears to be a new universe. The closing shot of the film finds the probe ship on course for a giant white sun...a beacon of light and hope, and perhaps even a new beginning for the human race (and again, robot-kind...).

Yet a generation of kids (this one included) grew up with the film...and never forgot it. Disney's first "PG" rated movie, The Black Hole was an one-of-a-kind combination of disparate styles and moods. It was a swashbuckling space adventure in the mold of Star Wars (1977), down to two cute robots (V.I.N.Cent and Old B.O.B) and mock heroics, but it was also oddly -- and thoroughly -- dark. Creepy even.

On an Earth spaceship in a dark corner of the universe, a mad Captain Nemo-type, Reinhardt, had transformed his human crew into drones; into slaves. He controlled his vast, cathedral-like ship via the massive, red robotic terror, Maximillian (who was equipped with propeller blades as a weapon and wasn't afraid to use them). At one point, Reinhardt even cryptically begged "save me from Maximillian..."

And the film's startling, do-or-die conclusion was a literal odyssey through Hell. Another of The Black Hole's unforgettable images: Reinhardt shunted inside the beast, Maximillian; his desperate human eyes entrapped inside a robotic shell.

Itself inspired by 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, The Black Hole seems to have been the inspiration for films such modern efforts as Event Horizon (1997). And, of course, we're due for a remake in the years ahead; though I doubt a new film can capture the pure, unique creepiness of the original. Hopefully, it can improve some of the film's dopier scientific flaws and dialogue.

In terms of look, The Black Hole was also something special. Outer space itself looked different (bluer...); the spaceship Cygnus resembled a vast haunted house; and the goose-stepping robots had a menacing but realistic air about them. Thematically, the film concerned how humans (and robots) faced the specter of the unknown: with madness (Reinhardt); with cowardice (Harry Booth); with blind devotion (Durant) and - thankfully - with heroism (Holland and the others). This was not an unimportant thing, since beyond the black hole laid a Manichean afterlife of sorts; a binary choice of Heaven or Hell for all souls going beyond the event horizon.

I can't believe it's been thirty years since I first saw The Black Hole. I was in the fourth grade...and I was stunned (especially by the violent death of Dr. Durant). Time flies. Anyway, here's a snippet of my detailed review of the film, from earlier this year:

...in The Black Hole, viewers can detect a number of Manichean ideas expressed in the dramatis personae and the narrative situations. This is especially so during the metaphysical journey through the black hole in the finale, a strange religious twist on the trippy denouement of Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Mani believed that Evil had many faces...but that at all those faces were part and parcel of the same Evil, not different ones.

In The Black Hole, we see Maximillian and Hans Reinhardt as two faces of Evil (mechanical and human, respectively) and in their nightmarish last scene, these two evils literally join to become one: Reinhardt is subsumed inside the robot demon Maximillian. Hauntingly, we see Reinhardt's frightened human eyes peering out from the machine's mechanical shell. This is our last close-up view of the characters, of twin evils welded together.

This strange inhuman union occurs inside the black hole, in a realm that resembles a Boschean vision of Hell, with hopeless souls (the spirit-less humanoids) trudging across a Tartarus-like underworld of sorts as flames lick at the bottom of the frame. High atop a hellish, craggy mountain, the Maximillian/Reinhardt Hybrid rules, like Milton's Lucifer. In keeping with Manichean beliefs, this is visibly the realm of physical things: bodies, mountains, fire...materialism. It is no coincidence either that the production design of the film has colored Maximillian, Dr. Hans Reinhardt and Hell itself in crimson tones. This bond of red -- whether Reinhardt's uniform, Maximillian's coat of paint, or the strange illuminating light of Hell itself -- connects all of them as "the One Evil," not separate evils, conceived by the ancient philosophy.

Contrarily, the four survivors of the Palomino expedition (Holland, McCrae, Pizer and V.I.N.C.ent) find not Hell in at the event horizon, but rather a celestial cathedral of sorts. Their vessel, the probe ship, is guided through this realm of the spirit (not the body), by another soul...a white guardian angel of sorts. The protagonists temporarily seem to exit the world of the body, and the film reveals their thoughts -- past and present -- "merging" during a brief, strange scene involving slow-motion photography.

What this scene appears to portend is that the three humans -- and robot (!) -- have been judged by the cosmic, Manichean forces inside the black hole and found to be above "sin," hence their journey through the long, Near Death Experience-style "light at the end of the tunnel" and subsequent safe re-emergence back into space. Instead of remaining trapped in a physical Hell (like the Reinhardt/Maximillian hybrid), the probe ship and those aboard pass through the gauntlet of "spirituality" where nothing -- not even sin -- can escape, and arrive safely in what appears to be a new universe. The closing shot of the film finds the probe ship on course for a giant white sun...a beacon of light and hope, and perhaps even a new beginning for the human race (and again, robot-kind...).

Reinhardt's final utterance before entering the crucible of the black hole is simply a mumbled..."all light." This might be an allusion to William Wordsworth's poem, An Evening Walk Addressed to A Young Lady: "all light is mute amid the gloom," It may be Reinhardt's (too late...) recognition of the fact that just as he has squelched out all light in the souls of his crew; so will the black hole mute out his spiritual light...sending him into utter, eternal darkness.

The climactic and symbolic final moments of The Black Hole -- long a subject of debate among the movie's detractors and admirers -- fits the tenets of Manicheism perfectly, positing for us the metaphor of devouring black hole as a spiritual testing ground or judgement day: one where humans understand that the secret of creation...is man's spirituality; his sense of morality. So the use the movie ultimately puts the black hole to is not scientific at all, but rather spiritual, religious. For some viewers, that may simply be a bridge too far in belief. For other's, it's a recognition, perhaps, that man must ultimately reckon with himself, especially when facing the Mind of God.

Labels:

The Black Hole,

tribute

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Sunday, December 20, 2009

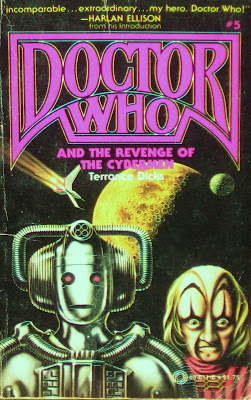

Pop Art: Doctor Who/Pinnacle Edition (1979 - 1982)

Labels:

books,

Doctor Who,

pop art

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Saturday, December 19, 2009

CULT MOVIE REVIEW: The Reflecting Skin (1991)

Every now and then, a movie catches you by surprise...even as you're experiencing it.

Every now and then, a movie catches you by surprise...even as you're experiencing it.Sometimes, a movie even seems to coalesce suddenly before your very eyes (and in your heart). And as it reaches that final, human crescendo, you're left unexpectedly breathless, overcome emotionally by the movie's impact.

Such a movie is Philip Ridley's bizarre 1991 effort, The Reflecting Skin. It's not an easy film to watch -- or even process -- and often it has been attacked for visual and thematic elements that some critics perceive as pretentious.

Writing in The Austin Chronicle, Steve Davis noted "The Reflecting Skin may befuddle you by what it's all about, but like a vivid dream, you'll have a difficult time forgetting it."

Time Out opined: "The complex, non-linear narrative is almost operatic in its visual and emotional excess, employing exaggerated camera angles, saturated colours and an ultra-loud soundtrack to create a heightened, sometimes dangerously portentous reality."

Most often, The Reflecting Skin is compared with David Lynch's films, and it has even been termed "Blue Velvet with Children" on occasion.

Many of the comparisons to Lynch's work are likely apt, but The Reflecting Skin is no mere imitator. It casts a singular, hypnotic spell. The film is legitimately haunting and affecting, and it's one of the few cinematic efforts I've seen (besides Menzies' Invaders from Mars [1953]) that visually captures the essence of childhood: the anticipation; the boredom; the excitement...the terror. Even the inescapable end of chidhood: the death of innocence.

Set in a lonely prairie town in post World War II Idaho, The Reflecting Skin tells the story of a boy named Seth Dove (Jeremy Cooper). He's going to be nine years old soon, and life is...strange and mysterious.

Set in a lonely prairie town in post World War II Idaho, The Reflecting Skin tells the story of a boy named Seth Dove (Jeremy Cooper). He's going to be nine years old soon, and life is...strange and mysterious.For one thing, Seth's mother is brutal and draconian in her punishments (she force feeds Seth water until his bladder is literally ready to burst...).

For another thing, there's a strange but lovely new neighbor in town, the Widow Dolphin Blue (Lindsay Duncan). After reading a comic book called "Vampire Blood," Seth becomes convinced that she's actually a vampire. Dolphin even confides in the boy that she's two hundred years old.

But then a mysterious black cadillac begins haunting the wind-swept, endless country roads, and Seth's young friends begin to turn up dead...murdered.

Seth's father, a closeted, repressed gay who was once caught kissing a 17-year old man, is linked to the crimes because of his past history, branded a pedophile by the police, and soon commits suicide (by swallowing gasoline and immolating himself). Life goes on for Seth and the murders continue too, exonerating his father too late.

Seth's older brother, the handsome Cameron (Viggo Mortenson) returns home from the war, the Pacific Theater specifically, to care for the troubled Dove famly. The troubled veteran (who has witnessed atrocities...) promptly falls in love with the Widow Dolphin. Seth tries to warn his brother about her: she's a vampire and will kill him. Bafflingly, Cameron is already losing his hair, and his gums have begun to bleed...

Cameron can't be dissauded in his passion for Dolphin. He and the Widow Blue plan to escape the isolation of the prairie town, and Seth grows ever more desperate to stop their flight from his life. But then the black cadillac returns and claims one finatl victim.

This time, because of the identity of that corpse, Seth can't deny "reality." There are no easy vampire myths to hide behind. No more easily-explainable monsters. Alone, he runs into a golden wheat field and screams at the blue, wide-open sky. Innocence is hell. Innocence is dead.

This synopsis only covers a portion of Reflecting Skin's unusual tapestry. I didn't mention the aborted fetus that Seth discovers...and mistakes for an angel. I didn't mention the man in the eye patch. Or the fact that all the corpses "returned" by the mysterious black cadillac are strangely immaculate...ivory white, but with no sign of wounds.

On first glimpse, Seth seems to live a beautiful, repetitive life. He plays among golden wheat fields, draped in an American flag...spending his days with his friends. At one point, Ridley orchestrates a low-angle shot of Seth running towards the camera, through the fields; the sky unmoving and permanent behind him. The effect of the shot is that Seth appears to running as fast as he can, but going nowhere. It's a perfect metaphor for childhood as it is lived: it seems to last forever. All one giant game.

But this perfect childhood existence is punctured by inexplicable invasions from adulthoood. Seth's Mother and Father are awash in secrets; alienated and judgmental. And Dolphin Blue sits by herself in her lonely house surrounded by artifacts belonging to her dead husband...even strands of his hair. "Nothing but dreams and decay," she tells the boy with glazed indifference. Then, Seth and his friends catch Dolphin masturbating...another strange, inexplicable "adult" thing.

As the movie points out (particularly with images), Seth attempts to process the murders, the mayhem, the sorrow and secrets of the adultt universe in a way a child legitimately would. Dolphin affects him in a strange way -- disturbs his young mind -- and so he interprets the unfamiliar in a familiar way: as a vampire. When this creature of the night threatens to "steal" his brother, that interpretation becomes all the more powerful. Seth must save his brother from an imaginary monster; a phantasm of youth....a fairy tale. But a vampire, at least, is something that a child can comprehend. Vampires have rules; and there are ways to kill vampires. Real life isn't like that.

Then, in a scorching, heart-wrenching moment, Seth's world crumbles around him. He is forced, by circumstance and violence, to learn that there are no vampires. This discovery, leading up to the film's climax, totally annihilates what remains of his innocent perception. At the end, there are no monsters, just other people.

So -- cast in shadow and silhouette -- Seth weeps and screams at his involuntary initiation into adulthood. This valedictory shot -- a lonely boy crying heavenward in a pastoral setting -- has been charged to be cliched or pretentious by some, but that's a cynical and unsentimental reading of an artistic composition. The final shot is a primal scream against forcibly growing up. Seth's realization that he has been thrust into a world without monsters and without magic is utterly heart-rending, especially if you have ever observed up close the innocence and wonder of a trusting, believing child.

At one point in The Reflecting Skin, The Widow Blue tells Seth that childhood is a nightmare and that "innocence is hell." But she goes on to tell him that "it only gets worse." She enunciates the humiliations and degradations of growing old. Losing hair; losing memory; succumbing to arthritis, senile dementia, and more. She ends the litany with a warning: "Just pray you have someone to love you."

Seth doesn't understand her warning at the time. In the magical cocoon of childhood, he can invent friends (the fetus angel for instance...), rely on others to care for him (even his brittle mother), and hope for the future. But when he crosses the threshold into adulthood, however, he starts to understand the lonely, spiritually-wounded Cameron, and the need to connect to someone real; something tangible.

"Sometimes, terrible things happen quite naturally," The Reflecting Skin informs us, and Ridley's movie contrasts views of beautiful (if overwhelming...) nature with images of human ugliness. So much of what occurs in The Reflecting Skin happens between the lines. We ask questions but don't get answers. With his hair falling out and gums bleeding (and history in the Pacific...), was Cameron exposed to the atomic bomb and suffering from radiation sickness? If so, the movie concerns the death of innocence on a much grander, even global scale.

The Reflecting Skin is a grim movie, one that charts the death of innocence as an inevitable but sad rite of passage. The movie is dark in a real way (not a faux, Hollywood way,) immensely powerful in emotional terms...and once you've seen it -- I promise you -- you'll never, ever forget it...

Labels:

cult movie review

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Interview with Chris Carter

If you boast any familiarity with my blog, you probably already know that -- across the last five years -- I have written frequently abut the TV and film productions of Chris Carter and Ten Thirteen Productions.

If you boast any familiarity with my blog, you probably already know that -- across the last five years -- I have written frequently abut the TV and film productions of Chris Carter and Ten Thirteen Productions.There are many reasons why I find myself continually drawn back to Carter's oeuvre. In broad terms, these reasons involve television history, the artistry of the particular programs, philosophy, and of course, personal taste.

Historically speaking, The X-Files and Millennium have grown virtually synonymous with the decade of the 1990s. Carter's programs captured the Zeitgeist of that epoch in sometimes challenging, sometimes stunning fashion.

By the end of the decade, various Ten Thirteen productions had gazed at the teen culture ("Syzygy,") pondered the Human Genome Project ("Sense and Anti-Sense,") skewered nineties tabloid culture ("The Post-Modern Prometheus"), satirized Scientology ("Jose Chung's Doomsday Defense"), peeked behind the closed-door mores of our affluent gated, McMansion communities ("Arcadia," "Weeds"), considered domestic terrorism ("52266"), dissected the mentality of cults ("The Field Where I Died"), and much more. This is Who We Were.

In terms of my continued appreciation of these series, I find myself again relying on Roger Ebert's insightful and useful refrain -- that it isn't what a movie (or TV program) is about that's important; it's how that production is about the narrative that truly matters.

And the "how" of Chris Carter's genre programs -- The X-Files, Millennium, Harsh Realm, and The Lone Gunmen -- is also the thing that perpetually intrigues and fascinates me. Specifically, I enjoy that these productions invariably deploy symbolism and literary allusion to further their themes. I've written about that facet in regards to Millennium, specifically, in my essays: "Enemies Within: Chris Carter's Millennium and America's Suburban Apocalypse, and "Snakes in the Grass and Snakes in the Open: Animal Symbolism in Millennium's Second Season."

I also admire the unconventional and cinematic visuals forged on these series, which stand apart from the majority of dramatic programs in television history. Television tends be...visual radio.

But not The X-Files, Millennium or Ten Thirteen's other works. They regularly utilize expressive, unconventional camera-work and always seem to find a way for the image to marry theme. If you have any doubt of this fact, just go back and watch The X-Files episode "Triangle," a dizzying, audacious balancing of "real space and time" with "fantasy space and time" in the Bermuda Triangle. It's Alfred Hitchcock's Rope meets the split-screen climax of De Palma's Carrie meets The Wizard of Oz. And that's just one example.

Notably, Carter's programs were also at the vanguard of the movement in dramatic television towards multi-episode, multi-season story arcs. And gazing across nearly 300 hours of filmed entertainment, I find myself fascinated by the connections between Ten Thirteen's many works; and the consistency of world view I see across the spectrum of Carter's universe.

For shorthand, you might call this "the Chris Carter mystique," or his "brand." It's the same thing with Joss Whedon (another artist I deeply admire): the alert viewer will be aware within minutes that he has stepped into Chris Carter's world.

So, after I received a happy birthday note from Chris Carter last week (!), I decided this was a great opportunity to open a dialogue with him regarding some of these ideas. To my delight, he agreed to a wide-ranging interview, and that's what you see transcribed below. I re-arranged the interview to group my questions by themes to present, hopefully, a cohesive picture.

The Building Blocks: Symbolism, Story Arcs, and "The Chris Carter Man"

JKM: One of the threads I've noticed running throughout your work is your use of symbolism.

For example, the Yellow House as paradise and then paradise lost in Millennium. Or the Arthurian Chair in Harsh Realm. I guess my question is simply, why?