My favorite movie of all time - bar none - is Franklin J. Schaffner's Planet of the Apes, from the turbulent year 1968. I also happen to believe this movie is the finest, most artistic genre work produced in well over one hundred years of the cinema.

My favorite movie of all time - bar none - is Franklin J. Schaffner's Planet of the Apes, from the turbulent year 1968. I also happen to believe this movie is the finest, most artistic genre work produced in well over one hundred years of the cinema.Yes, I realize there are other contenders for best "sci fi" film. Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey is a great film; no doubt. And the Russian version of Solaris from the 1970s is another masterwork (and an unacknowledged well-spring of ideas for many American films and television programs). And sure, there will be those folks who champion Blade Runner (1982), or The Matrix (1999), or even Star Wars (1977). But the purpose of this post is not to argue for these films; or for that matter to put them down; rather it is to laud Planet of the Apes for what it remains almost forty years after its theatrical release: a remarkable and visually-accomplished text that functions (and excels) on a variety of thematic and narrative levels simultaneously.

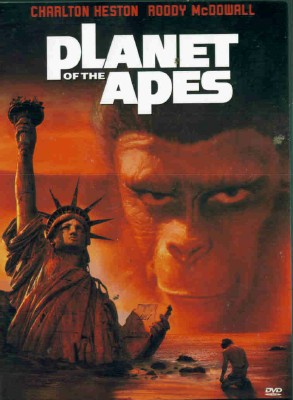

Now, mind you, I'm not writing about the 2001 abomination, the re-imagination of Planet of the Apes directed by Tim Burton. No. I'm talking about the first film adaptation of the Pierre Boulle novel, Monkey Planet. The one that starred Charlton Heston, Maurice Evans, Linda Harrison, Kim Hunter and Roddy McDowall and spawned four sequels, a TV program and an animated series. We're clear on that point, right? Okay, let's move on.

Let's re-cap the film's plot, in case you haven't watched the film recently. A spaceship carrying four human astronauts crashes on a mysterious planet after several months in deep space. The three surviving astronauts, Taylor (Charlton Heston), Dodge and Landon, believe they have traveled 300 light years from Earth, to somewhere in the constellation Orion. They also check their ship's chronometer and learn that Dr. Hasslein's theory of time travel at light speed is correct. Although they left Earth in 1972, their chronometer verifies that it is now November 25, 3978.

The humans brave an arid, seemingly endless desert as they leave the dead lake where their ship crashed, and soon discover that humans also exist on this world. But that they're mute savages...unevolved and unsophisticated.

Then comes the real shocker: the planet is ruled by intelligent, civilized simians...apes! The astronauts lose track of one another in a ferocious hunt of the savage humans (a tense, sustained action set-piece), and Taylor ends up in Ape City as a ward of a chimpanzee scientist, Dr. Zira (Kim Hunter), an expert in human behavior. She and her fiancee Cornelius (Roddy McDowall), a chimp archaeologist, soon learn that Taylor - unlike all the other humans they have encountered - can speak; can reason. They defend this specimen (whom they term "Bright Eyes") from Dr. Zaius (Evans), a self-righteous orangutan administrator who serves as both Minister of Science and Chief Defender of the Faith. Zaius, as it turns out, has very good reason to despise humans, and to fear Taylor.

Taylor and a savage (but sexy...) consort, Nova (Linda Harrison), flee Ape City with the aid of Zira and Cornelius (who have been accused of heresy for defending the human and advancing the "insidious" theory known as evolution), and head back to the Forbidden Zone to seek the truth of Taylor's heritage. The apes believe he is a missing link between primitive man and civilized ape, but Taylor wants to show them his spaceship to confirm his story of having arrived from another planet. Finally, as the ocean tides endlessly beat against a rocky shore, Taylor comes face to face with mankind's destiny. A strange rusted statue jutting out of rock and sand is mankind's ultimate epitaph...and Taylor's evidence that he has - finally - returned home. In the sand he sees it. The Statue of Liberty. "You finally did it!" He exclaims, pounding the sand at his feet. "You blew it up! You maniacs...God damn you all to Hell!"

There are a number of reasons why I admire Planet of the Apes, and I hope to enumerate them all here, although frankly, it could take days. Many of the reasons for my admiration concern the nature and disposition of the film's protagonist, George Taylor and his "hero's journey." In particular, this astronaut (and the leader of the expedition to the stars), is an avowed cynic. Taylor boasts no faith in man or mankind when he leaves Earth for space. "Tell me," he rhetorically asks in the equivalent of a Captain's log, "does man - that marvel of the universe, that glorious paradox who sent me to the stars - still make war against his brothers? Keep his neighbor's children starving?" (The answer, by the way, to these interrogatives - with my evidence being the Iraq War and the situation in Darfur - is yes, absolutely).

Anyway, after landing in the wasteland of the Forbidden Zone, Landon and Taylor bicker about their predicament. Taylor has poked fun of his companion for displaying an American flag on the shore line of the dead lake. The absurdity of patriotism (and hence jingoism...a reflection of Taylor's earlier comments about man making war on his brothers...) in this place and time is not lost on a bitter Taylor. Angry, Landon asks him what makes him tick then, if not patriotism or nationalism. "You're negative; you despise people," Landon accurately summarizes his skipper's attitude. Taylor doesn't disagree. His reply is: "I just can't help thinking in the universe there has to be something better than man..."

As you can guess from the film's title, Taylor's quest for something in the universe better than man will soon turn into a cosmic joke...

So, these early scenes establish Taylor's character in a clever and artistic way. He's a cynic, a misanthrope. And suddenly, he finds him the only intelligent human on a planet of apes. The man who hates mankind is thus forced into the position of being the defender of the species. Ironic, huh? Taylor knows all of mankind's flaws too well (he calls our culture one in which there is plenty of love-making but precious little love...). He has searched the stars for something better, but now must be man's advocate and champion. What a rich and (ironic) set-up for the film's central debate, and one which fits the production's overriding conceit: that of a world turned upside down; of somebody who boasts one rigid agenda yet is forced by circumstance to countenance another.

I hasten to add, this character arc works even more splendidly because it is the self-same "from my cold, dead hands," Charlton Heston who essays the role of Taylor. Heston is far right-wing ideologue, and yet here he is...starring in a paranoid left-wing dystopic fantasy about what could happen if man does not curb his predilection for war and conquest. Having Heston - a virile and robust figure representing American strength and beauty - beaten, bruised, and literally stripped naked before the superior apes - works fiendishly upon the subconscious of the viewer. This is Ben Hur! This is Moses! And how the mighty has fallen...

Taylor's fascinating journey - from hater of mankind to last defender of the species - would mean little were he not faced with a powerful nemesis. Fortunately, the screenplay for Planet of the Apes (by Michael Wilson and Rod Serling) provides him a terrific opponent in Dr. Zaius (Evans). Zaius, like Taylor, is a man divided by two thoughts. On one hand, he is honor bound and professionally responsible for the advancement of science (and science by nature, is impartial). On the other hand, he serves as Chief Defender of the Faith, which means he must rigorously maintain the apes' belief in their own superiority, transmitted through the auspices of organized religion. "There is no contradiction between faith and science," he asserts to Taylor at one point in the film; but clearly...there is. Although Ape Culture is rife with commentary that asserts the simian as the supreme creature of the land ("The Almighty created the ape in his own image," is one very telling ape proverb), Zaius knows the dark truth: that apes rose because man fell; that the return of intelligent man would inevitably spell the end of the ape dominion.

What I love about Dr. Zaius is this fact: by some point of view - perhaps another "upside down" or "inverted" one, in fact - he is the film's unlikely hero. Yes, he hates man and is ruthless to mankind. He performs lobotomies on man and wants to see the species exterminated. Yet as we learn at the end of the film, he has good, nay valid reasons for his fear and loathing of humanity. After all, It was the humans, not the apes, who turned their cities into deserts (in a nuclear war). The 29th Scroll - part of the ape religion, thus warns: "beware the beast man. For he is the devil's pawn." Zaius understands the meaning behind the flowery prose and tells Taylor. "The Forbidden Zone was once a paradise. Your breed made a desert of it ages ago." In some sense, by preventing the new ascendancy of man, Zaius is saving the planet Earth for future generations (as he tells young Lucius). Or thinks he is, anyway.

So Planet of the Apes offers two very strong characters in dynamic opposition. It sends each of them on a journey in which their faith is tested by each other, and ultimately their prejudices are reinforced. Zaius believes man is a primitive destroyer of all things, and after dealing with Taylor, believes that more strongly than ever. Taylor leaves Earth believing man is a war-like barbarian who would destroy his brother for his brother's land, and when faced with the Statue of Liberty, realizes that he was absolutely right. Man's hunger for territory, for war, did ultimately destroy him. Made the apes supreme and turned the world "upside down."

But the character dynamics are only a part of the reason why Planet of the Apes is a great film. I believe that any science fiction film deserving of the moniker "great" must - after some fashion - carry audiences to a different and fantastic reality or world. Accordingly, another rewarding aspect of the Schaffner film involves the multi-layered depiction of Ape Culture. The full breadth of this "alien" world is often revealed in a most clever (and often funny...) way. Without ever seeming like either a travelogue or a half-assed parody, the film cleverly reveals the details of this upside-down world. We see an ape funeral (which includes the eulogy: "I never met an ape I didn't like...); we visit ape medicine (in the hospital) and learn about ape affirmative action ("the quota system was abolished..." says a disenfranchised chimp); take a trip to a natural museum (where humans - including astronaut Dodge - are stuffed and posed in little dioramas that mimic their "natural" environment), and even head full bore into the byzantine Ape legal system.

On the latter front, we witness an ape tribunal in which the notion of see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil, is dramatized in funny visual terms (with the three orangutan panel acting it out). We also see Ape maps, ape markets, ape buildings, ape hunts, and so forth. The scope of this world is absolutely remarkable given production limitations of the time. We even learn that there's an animal (or in this case, human...) rights group, "An Anti-Vivisectionist Society." In other worlds, the "ape culture" is a twisted, inverted reflection of our own.

The apes and their society are depicted in glorious, believable terms thanks to the exquisite make-up of John Chambers and the glorious production design, but this is a film, in the last analysis, about man, not apes nor special effects. The ape society exists as a mirrorof our own; as an indictment of our world. Therefore, the ape proverbs which we laugh at, like "human see, human do," reveal the arrogance that comes with a species' assumed superiority over the world and his other species.

"Why do men have no souls?," asks one ape of Taylor during the tribunal. "What is the proof that a divine spark exists in simian minds?" Remarks like this make viewers laugh with recognition. How can apes believe they are God's chosen ones? And then viewers step back and realize the uncomfortable truth. Ummm...that's what we believe, isn't it, as human beings? That we are superior to animals like cats and dogs (oh, they have no souls, right?) and that we're created in God's image. Suddenly, the film makes us realize that we are as misguided and silly as the self-righteous apes.

"All men look alike to most apes," Zira notes at another point, touching on racism, and so on, thus furthering the social commentary. Basically, the ape society is structured in Planet of the Apes to make us realize the insanity and "upside down" quality of our own religious precepts. As long as we cling to such arrogant and egotistic notions - such irrational notions that the world is ours to do with as we please because we're God's "select" - we are at risk of destroying ourselves.

Zaius has a good motive. He wants to preserve his people. Ye he is also a scripture-quoting racist who believes in the supremacy of his kind, even as he is "guardian of the terrible secret" about man. He is, like man himself, a hypocrite. He offers religious platitudes ("Have you forgotten your scripture?") in the place of science, and attempts to keep the truth hidden from his culture. And that truth is, simply put, that the supremacy of a species - any species - is fragile. Apes did not always rule the world; and man was not always cursed. And the tables could turn again at any time...

Planet of the Apes is also fervently anti-war, which is important since the film was released at the height of the Vietnam "police action." Here, the screenwriters imagine a world wherein man's predilection to "kill his neighbors for his neighbor's land" is taken to its logical conclusion: the destruction of civilization together. The Forbidden Zone is what's left of New York after a deadly nuclear war. The film's final image, of the Statue of Liberty half-buried in the sand - says it all. Mankind has forsaken his spoken ideals of peace and love for wars of conquest. He has destroyed himself and his world over ideology (capitalism vs. communism, we assume...). Consequently, the beliefs we hold now about freedom, liberty and God's will will ultimately prove nothing but ruined artifacts for future archaeologists to puzzle over.

Other reasons why Planet of the Apes is tremendously successful:

On the latter front, we witness an ape tribunal in which the notion of see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil, is dramatized in funny visual terms (with the three orangutan panel acting it out). We also see Ape maps, ape markets, ape buildings, ape hunts, and so forth. The scope of this world is absolutely remarkable given production limitations of the time. We even learn that there's an animal (or in this case, human...) rights group, "An Anti-Vivisectionist Society." In other worlds, the "ape culture" is a twisted, inverted reflection of our own.

The apes and their society are depicted in glorious, believable terms thanks to the exquisite make-up of John Chambers and the glorious production design, but this is a film, in the last analysis, about man, not apes nor special effects. The ape society exists as a mirrorof our own; as an indictment of our world. Therefore, the ape proverbs which we laugh at, like "human see, human do," reveal the arrogance that comes with a species' assumed superiority over the world and his other species.

"Why do men have no souls?," asks one ape of Taylor during the tribunal. "What is the proof that a divine spark exists in simian minds?" Remarks like this make viewers laugh with recognition. How can apes believe they are God's chosen ones? And then viewers step back and realize the uncomfortable truth. Ummm...that's what we believe, isn't it, as human beings? That we are superior to animals like cats and dogs (oh, they have no souls, right?) and that we're created in God's image. Suddenly, the film makes us realize that we are as misguided and silly as the self-righteous apes.

"All men look alike to most apes," Zira notes at another point, touching on racism, and so on, thus furthering the social commentary. Basically, the ape society is structured in Planet of the Apes to make us realize the insanity and "upside down" quality of our own religious precepts. As long as we cling to such arrogant and egotistic notions - such irrational notions that the world is ours to do with as we please because we're God's "select" - we are at risk of destroying ourselves.

Zaius has a good motive. He wants to preserve his people. Ye he is also a scripture-quoting racist who believes in the supremacy of his kind, even as he is "guardian of the terrible secret" about man. He is, like man himself, a hypocrite. He offers religious platitudes ("Have you forgotten your scripture?") in the place of science, and attempts to keep the truth hidden from his culture. And that truth is, simply put, that the supremacy of a species - any species - is fragile. Apes did not always rule the world; and man was not always cursed. And the tables could turn again at any time...

Planet of the Apes is also fervently anti-war, which is important since the film was released at the height of the Vietnam "police action." Here, the screenwriters imagine a world wherein man's predilection to "kill his neighbors for his neighbor's land" is taken to its logical conclusion: the destruction of civilization together. The Forbidden Zone is what's left of New York after a deadly nuclear war. The film's final image, of the Statue of Liberty half-buried in the sand - says it all. Mankind has forsaken his spoken ideals of peace and love for wars of conquest. He has destroyed himself and his world over ideology (capitalism vs. communism, we assume...). Consequently, the beliefs we hold now about freedom, liberty and God's will will ultimately prove nothing but ruined artifacts for future archaeologists to puzzle over.

Other reasons why Planet of the Apes is tremendously successful:

* It functions both as a satire and allegory and as an action film. It is possible to enjoy the film simply as a rip-roaring action piece, if you're so inclined. From Taylor's opening hunt in the jungle, to Taylor's attempted escape from Ape City, to the final shoot out in the Forbidden Zone, the film's pace never lets up.

* This film boasts more quotable lines than any movie this side of Spinal Tap. "Take your stinking' paws off me, you damn dirty ape," is one example, but there are others. "It's a mad house, a mad house!" is a personal favorite; one which I find myself using here every day...

* Planet of the Apes is beautifully filmed; which gives it an additional sense of authenticity. Remember, Planet of the Apes was crafted well before the days of CGI. This means that filmmakers actually had to be clever rather than merely rely on digital imagery to make things look cool. The film's opening crash sequence is a prime example. There are no conventional modern special effects to speak of here. Instead, the film adopts dizzying P.O.V. camerawork, as if we're riding the nose of the rocket. The footage has been tweaked to make it more dramatic - sped up and turned upside down at points - to register the speed and angle of the crash. Even without contemporary visuals, however, the sequence is edited brilliantly. The terror of the crash is palpable.

A corollary: the film's location work is nothing short of stunning. So much of this movie's plot is "sold" to us in dramatic long shot, using the odd rock outcroppings of Death Valley and "big sky" of Arizona to represent the otherworldly Forbidden Zone.

* The best "surprise" ending in film history. This should be no shocker, since Rod Serling was a co-author of the screenplay and many of his Twilight Zone episodes featured dramatic, O'Henry-style endings. Here, the discovery of the Statue of Liberty is (on first viewing...) shocking, and on ensuing viewings remains chilling. It perfectly encapsulates the film's theme of a world-overturned. Man's ideals: buried.

On a similar note, the film is rife with other powerful symbols too. The small American flag in the sand of the Forbidden Zone; the strange scarecrows in the desert, like giant "X's" blotting the landscape; the human doll from ages past which lets out the cry of "Maaa-maaa."

Also: the shore line.ocean is a powerful symbol too, in a sense. The waves just keep rolling in from the ocean. Rolling in and washing away everything...for all time. The ocean and the waves are cleansing on one hand, and impartial on the other. No matter what man (or ape) does, the tides just keep coming and ages pass. Civilizations rise and fall unmourned, and the tides take no notice.

* The film's timelessness and continued relevance. Hmm, let's see. In 1968, there was the war in Vietnam. Today we're at war in Iraq, another quagmire. In 1968, America feared a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union, today, it is North Korea and Iran. In 1968, Planet of the Apes took well-conceived and pointed shots at the American religious right, dramatizing the ape culture as a theocracy in which science and new ideas were anathema; and only perpetuation of "faith" and legend mattered. Evolution in the film is called "an insidious theory," and Zira and Cornelius are indicted for advancing it...even though they appear to have proof. Hmmm, look around at new movies like Jesus Camp, or at school boards in Kansas; which wanted to outlaw teaching evolution in the public classroom. Why, just last year there was a serious debate in this country(which included President Bush...) about teaching intelligent design ("the ape was created in God's image...") in the classroom. Clearly, all of the ideas in Planet of the Apes are as relevant (if not more so) today than they were forty year agos. The war on science, the killing of brothers to own our brother's land...all this continues (alas...) today. So Apes has translated well to the "next generation." The worries that dominate the film are still our worries, almost half a century later.

In closing, Planet of the Apes is, in some senses, a ruthless and brutal bit of business. It doesn't play games. It reveals to us a new world where man - because of his arrogance and hypocrisy - has been brought low before a new master race. The humor (seen in many ape proverbs...) is chilling. The hero is a misanthrope forced to defend mankind out of necessity, and that makes him unlikeable...but our only shot at survival. The ending is...startling, terrifying, the ultimate statement about mankind's predilection to destroy himself. I can't think of another science fiction film that so effortlessly creates a total world; adheres to a central theme...and which enlightens and terrifies.

I always thought Planet of the Apes was so much more than just a sci-fi flick with a great story; thanks for such a great post about why.

ReplyDeleteWOW! What a great commentary on truly the best Sci-Fi movie ever made. I think that this is Rod's crowning achievement. Watching it for the first time when I was 8 years old, it left an indelible mark in my imagination. To this day I am still learning from this movie, the shoreline symbolism is brilliant. Thank you Mr. Muir for your insight and great narrative on this classic.

ReplyDeleteThe racism is driven home even further by the divisions in Ape society. Chimps vs. Orangs vs. Gorillas, none really trusting each other. I can envision the scene where Ursus's gorilla son brings home his chimp girlfriend...

ReplyDeleteGreat review. I'd like to add that I saw the movie in 1968 with my father at a drive-in when I was only seven years old, and it scared the crap out of me. You see, my dad always used to watch the evening news and the reporting was always about the Vietnam war, where the Americans were fighting GUERILLAS in the jungle that you'd never see. So when I processed this movie through my child's mind, I actually thought it WAS REALLY DEPICTING a war between humans and apes that was happening in the jungles of Vietnam! I thought it was a kind of documentary.

ReplyDeleteI loved your analysis. I have used this movie in Science and World History classes to talk about several things going on in the 1960s:

ReplyDelete1. Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" and the notion that animals are in fact intelligent and need be respected.

2. Jane Goodall's discoveries on chimp intelligence, as well as Dian Fossey's work with gorillas.

3. The Cold War, obviously, and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

4. Man going to the Moon, the Space race.

Thanks.