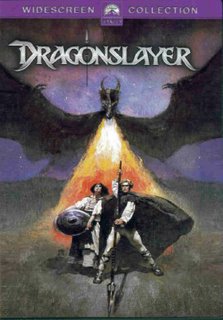

Matthew Robbins' early-1980s fantasy film, Dragonslayer, is another one of those cinematic gems that tends to get overlooked in the rush to canonize the new. Especially these days, in the shadow of the CGI Lord of the Rings saga.

Matthew Robbins' early-1980s fantasy film, Dragonslayer, is another one of those cinematic gems that tends to get overlooked in the rush to canonize the new. Especially these days, in the shadow of the CGI Lord of the Rings saga.And yet, here's another twenty-five year old genre film that remains, even today, a beautifully-crafted effort (like Outland, Hangar 18, or Dark Crystal). In toto, Dragonslayer is a film of breathtaking visuals, terrific action, and it features a great "villain" in the form of a fire-breathing dragon...an effect which still convinces, even today. So yeah, I'd say this film is a classic.

Dragonslayer dramatizes the story of young Galen (Peter MacNicol), the apprentice to a wise but aged wizard named Ulrich (Ralph Richardson). One day, a delegation from Urland arrives at Ulrich's keep, and petitions his service to dispatch a terrible dragon that is tyrannizing the village. Seems that this dragon once laid waste to Urland with unbridled wrath, but then the new King (Peter Eyre) came to an accord: Twice a year, he would conduct a town-wide lottery, and in the end, the two virgins selected would serve as both a sacrifice and appeasement to the horrible dragon (described in the film as both "pitiable" and "spiteful.") But some of the Urlanders know that this lottery is a devil's bargain, including Valerian (Caitlin Clark), a young girl who has disguised herself as a man since childhood to avoid being chosen as a human sacrifice.

When Ulrich unexpectedly dies in a test of his power, young and inexperienced Galen assumes control of his master's magical amulet and takes on Ulrich's final task himself: the matter of slaying a dragon. But he must contend with corruption in Urland, and face one of the King's more evil minions, Tyrian (John Hallam) as well as his own fears about battling the fire-breathing demon...

Dragonslayer is an exquisitely-crafted fantasy, and as such, it features many of the qualities that dominated that genre in 1980s cinema. There's the death of a wise master (also featured in Dark Crystal, Tron and Return of the Jedi), and also the ascent of an apprentice (ditto). But perhaps Dragonslayer is better for the things that it does differently than those similarities to other genre flicks. For instance, for a film in a "romantic" genre, the movie is distinctly anti-romantic. Princess Elspeth (Chloe Salaman), for instance, is a noble and beautiful character who willingly submits herself to the lottery when she learns that her father has kept her out of it all her life. What does this noble woman get for her troubles and pure morals? Well, the last we see of her, hungry baby dragons are snacking on her bloody, severed body parts. That's not the typical fate of a princess in these films...

Likewise, I admired how the film had a melancholy feel of time's passage, of an era ending as another begins. There's a recognition in Dragonslayer that the time of magic was ending and the era of Christianity was taking its place. "Magic...magicians...it's all fading out from the world," one character states, "and that means the dragon will die too." And sure enough, when the battle is won and the dragon is dead, we see a Christian priest standing over the splattered (and gooey...) corpse (on a hill), ignoring the real hero, Galen, and instead commenting that "We thank the Lord for this deliverance," as though Jesus himself had slain the winged-beast. In other words, one religion has been substituted for another.

Dragonslayer also focuses on human corruption as the second dragon that Galen must slay to ascend to true hero-dom. The King of Urland accepts bribes to keep the daughters of the wealthy (including Elspeth) from the lottery...meaning that the town's "sacrifice" falls only on the poor, the wretched, those without power. Anyway, the king is also more interested in the power of the amulet (and to holding on to his own power) than defeating the dragon, and that's why he's made a coward's bargain with it. "You can't make a shameful peace with dragons," Galen protests, but that is precisely what has occurred in Urland. It has a leader who would rather let a few suffer for the many, while he obsesses on ways to turn lead into gold.

In the final analysis, the success of any fantasy film rests on the efficacy and success of its visuals, and it is here that Dragonslayer truly excels. The ghoulish shot of the baby dragons feeding on lovely Elspeth is a magnificently grim moment in the film, and there are others of pure awe. For instance, when the the dragon's lair is revealed for the first time, the camera pans from the opening of a high cave down into a river of fire (where the dragon awaits...). There is a magnificent pullback, and then a lengthy pan across the breadth of this hellish domain, and, well -- you'll believe a man can fry. Like the beast it hides, the cave is a terrifying place, and one understands immediately Galen's jeopardy

Then there's another great shot near the climax, with the imposing dragon landing magnificently upon a high pinnacle of rock, during an eclipse...clouds racing behind him. It's a shot, I hasten to add, with no CGI elements. Instead, it's a combination of stop-motion animation, matte work and miniatures. It's really quite amazing to behold the craftsmanship of such a shot, and much of the film works because the dragon - once revealed - is a tangible and evil presence with his glistening skin, slithering tail, and cracked, scaly talons.

Dragonslayer came out of the British cinema (and Pinewood Studios) in the early 1980s, and it succeeds where so many other "sword and sorcery" flicks have failed, I believe, because the entire enterprise is vetted with such attention to detail and period design. There is a total lack of artificiality or theatricality in this film. The characters sometimes appear with mud and grime on their faces. They bleed. Chambers are literally packed with period details, and we hardly have time to take them all in.

Fantasy should be high-flying, wonderful and "unreal" in the sense that there are different rules (like magic) in these world, but really, humanity shouldn't change in a good fantasy film. Human kind can be venal and corrupt, but also heroic, noble and wonderful, and in the final analysis, Dragonslayer is a memorable fantasy film because it showcases all the colors of mankind's heart. Some of us greet tragedy and suffering with more tragedy and suffering, but some of us -- idealistic young people like Galen and Valerian -- just know that the world can be a better place, and that they can be the ones to make it so. Even amidst the boiling caves, the fiery dragon's breath and all the swirling magical forces, Dragonslayer grounds itself in the universal truths of human nature and human life.

Hey George,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the reference. I'll have to check out that review. Dragonslayer is a great film...

A rare weak review.

ReplyDeleteLet's start with Ulrich;s death. It's pretty plain that he intends to 'die'. And it further points out the generational theme. Ulrich trusts Galen enough to 'die' and have Galen transport his ashes. The King has really only comtempt for the young.

Next, let's look at Princess Elspeth. She hardly 'submits' herself to the lottery -- she rigs it so that she's the one chosen!

And why even single out the priest at the end, and competely fail to mention that it's the King who takes credit for slaying the dragon -- a problem that he arguably caused?!

Also, the young dragons point out exactly why making a deal with the devil has problems. Do we really think that the Dragon is going to be satisfied with a couple virgins wth a hungry brood?

And no mention of the spear that's good enough to cut throgh an anvil, but is just a toothpick to the Dragon? Adain, this point's out how man doesn't have a good chance against nature.

For myself, the Dragon is not the villian, vut a stand-in for natural forces. They really can't be bargained with or truly defeated. The real villian is the King, and by extension, the establishment.

As for Galen and Valerian, they may believe that they can make the world a better place, but not because of anything that happens in the film. Though they survive, like Elspeth, they've been had.