Richard

Franklin (1948 – 2007) is a talent that more horror film fans ought to remember

and celebrate. A protégé of Alfred Hitchcock, Franklin created a number of

memorable genre movies in the late 1970s and early 1980s including Road

Games (1981) starring Jamie Lee Curtis, Psycho II (1983), the

vastly-underrated Link (1986) and the subject of this review: Patrick

(1978).

Like

contemporaries De Palma and Carpenter, Franklin had a very distinctive film

style. His films featured elaborate, expressive compositions of near technical

perfection, and because of his understanding of film grammar (film as a medium

for visual symbolism) many of Franklin’s cinematic works are unparalleled in terms

of their suspense.

Naturally,

Hollywood didn’t treat Franklin particularly well, and he returned home to his

native Australia in the early 1990s. I

had the good fortune to interview him for my book Horror Films of the 1980s

(2007), wherein we discussed various aspects of his work in the Reagan Decade. Today,

I recall him as a decent, well-spoken man who was generous with his time and

open about every aspect of his career.

Patrick

(1978) is not,

perhaps, Franklin’s most accomplished or consistent work or art, though it

remains intriguing in terms of its layered approach to the material. The film

was something of a phenomenon in the late 1980s (in the post-Carrie

[1976] aftermath) and was the movie that put Franklin on the map. Patrick

was also remade this year as Patrick: Evil Awakens (2014), which

I’ll review here tomorrow.

Although

Patrick could use some judicious editing (to get it down to around 95

minutes or so) -- especially in its third act -- the film is considered a

classic by many primarily because of Franklin’s slow-burn approach.

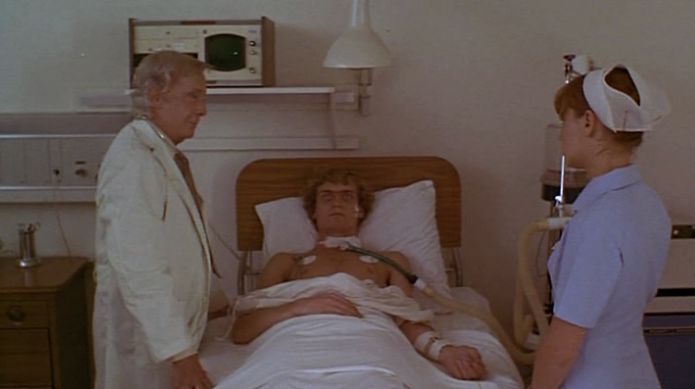

The

movie features a comatose patient, Patrick, as its antagonist. This bug-eyed

juggernaut never moves from his hospital bed and never even blinks, and yet is

on-screen and present throughout the picture.

The film features at least two jump scares of epic proportions when, at

long last, Patrick appears to break out of his standard paralysis.

One

such scare is pure simplicity. Patrick ever-so-slowly turns his head to face a

nurse who has gone to open the window by his bed. The slow-turn of his head, and the expression

on his face as he does so are more than enough to make the skin crawl.

On

a re-watch, I found other aspects of the film even more notable than I had

remembered. Everett De Roche’s script is unfailingly intelligent, and literate

too. And Franklin’s wicked sense of

humor is played out in terms of imagery, with certain sign posts forecasting

danger.

More

trenchantly, Patrick appears to be a story about what it means to be a

single, professional woman trying to make it alone in the 1970s. Susan

Penhaligon plays the likable lead character, Nurse Kathy Jacquard, a woman who

must navigate patriarchal expectations at every turn, whether from her

employer, a mad scientist (Robert Helpmann), her stalker-ish husband Ed (Rod

Mullinar), from whom she is separated, or the doctor, Brian (Bruce Barry) who

wants so desperately to bed her.

Given

the aggressive behavior of all these men and her so-called “unstable domestic situation,” it seems

natural, perhaps, that Kathy gravitates towards Patrick, a comatose patient who

doesn’t demand, only rebuffs…at least at first.

Kathy

-- a character termed “frigid” by her

husband -- must negotiate the modern world alone (a new home, a new job, and a

new social designation as single). Yet every man in her life seems to demand an

“electric” connection with her. Patrick is all the more insidious, because he

doesn’t encroach on her space, he invites her, essentially, into his own dark,

malevolent world.

Patrick artfully touches on many good ideas,

including the inhumanity of modern science, but the film is most successful if

one considers it a chronicle of Kathy’s personal journey as she contends with a

boogeyman whom the dialogue deliberately describes as a “creature from the Id.”

“Medicine

can prolong death much more effectively than it can prolong life.”

A

recently separated woman, Kathy Jacquard (Susan Penhaligan) moves to her own

apartment, away from her estranged husband, Ed (Mullinar), and seeks employment

at the private hospital for comatose patients, the Roget Clinic.

After

an interview with the stern Matron Cassidy (Julia Blake), Kathy is hired and immediately

taken to her new ward, the patient in Room 15: Patrick (Robert Thompson).

Patrick,

a young man (and murderer), has been comatose for three years, and shows no

signs of interface with the outside world. Sometimes, however, he spits when

nurses approach him, but Dr. Roget (Helpmann) dismisses this behavior as a mere

reflex action. Using a dead frog as an example, Roget describes for Kathy how electrical

impulses can travel through a body -- even appearing to animate it -- when life

and consciousness are gone.

Kathy

is intrigued by Patrick, and begins to show him a kindness not matched by the

facility at the institute.

When

Ed burns his hands mysteriously, however, and Brian -- an on-the-make doctor --

nearly drowns, Kathy begins to suspect that Patrick is somehow leaving his body

and terrorizing the men in her life.

“How

is our creature from the Id this morning?”

A

recurring motif in Richard Franklin’s Patrick is electricity.

In

the film’s “crime in the past” prologue, the audience sees Patrick toss an

electric heater into a bath-tub where his mother and her lover are canoodling. This

is the first example of electricity being related to passion, and murder.

After

the opening credits, and before we first see Kathy enter the Roget Clinic, we

are treated to a close-up of electric sparks emanating from a moving cable car.

This might be interpreted as indicator that the terror exemplified by Patrick

is about to return, and enter Kathy’s life, specifically.

A

neon entrance signs sparks as well (changing the word “entrance” to “trance,”

importantly), and when Patrick attacks Brian in his swimming pool, the pool

lights malfunction too. The film even opens with the sound effects of

electrical sparking (against a black screen), and Matron Cassidy is

electrocuted in the film’s last act.

The

implication, on a literal level, is that Patrick is able to move his

consciousness beyond the confines of his useless physical body via electrical

impulses.

On

a more metaphorical level, the leitmotif of electricity, or “sparks” seems

crucial to Kathy’s story, and her sense of ennui with her life. She has been designated by that terrible word “frigid,”

and both Brian and Ed assiduously pursue her, hoping to spark some kind of

romantic or sexual activity in return. She largely resists these efforts, not

because she is a cold fish (a male term for her condition), one feels, but

because neither man seems interested in her on anything beyond a surface of

physical level. She is clearly unhappy in her marriage, and seeks happiness and

fulfillment outside it, in the professional realm, at the Roget Institute.

Ironically,

Kathy is immediately drawn there to a man who cannot impose his physical wishes

upon her, or even make the first move.

In fact, any attempt to be intimate with Patrick is rebuffed instantly by

his reflexive spitting.

But

Kathy breaks down that wall, that barrier, and is able to show Patrick the kind

of physical attention that she can’t apparently, show Ed. She brings Patrick

back to life by touching him, all over his body, and asking him if he can “feel”

it. For once, she is in the driver’s

seat, she is the one leading the dance, so-to-speak.

Whereas

the aggressive, bordering-on-inappropriate attention of Ed only pushes Kathy

further away, Patrick’s inability to relate or perform at all draws her closer,

and brings her into his world. Where Ed stupidly attempts to force Kathy into

sexual intercourse she doesn’t want (“so

much for a woman’s rape fantasies,” he insensitively quips…), Patrick

cannot, apparently, make any advances whatsoever. Dr. Roget even describes him in

physically and sexually unthreatening

terms, calling Patrick “160 pounds of

limp flesh.” The word limp has a

pretty obvious connotation in terms of sexuality.

Finally,

of course, Kathy realizes that this isn’t precisely so, that Patrick is ultimately

no different than either Ed or Brian, and that he too makes aggressive demands

on her. The film’s most infamous line,

perhaps, is “Patrick wants his hand job,”

a statement that again forces an overt sexual demand upon Kathy that she finds

uncomfortable. The film’s last act sees

Kathy, rather than being acted upon, taking dynamic action to end Patrick’s

influence. But in a sense, she also rescues Ed and Brian, a turnaround of the

relationship status quo that empowers her.

Intriguingly,

Matron Cassidy, though emotionally distant, is also a strong female character.

For a long stretch of the film she acts only according to Dr. Roget’s bizarre

and draconian wishes and orders, but finally -- reckoning with her own morality

– she takes a stand to end Patrick’s so-called “life.” Patrick kills her before she can turn the

power off on him, but in terms of the character, Cassidy undergoes the same

sort of journey towards independence that we see in Kathy. She ultimately finds

the confidence to live according to her own moral code, and not by the edicts

of the domineering man in her life. She sees Patrick’s life as a cruel one that

should not be prolonged, and she no longer ignores her own voice.

Above,

I noted director Franklin’s sense of humor, and many visuals in the film humorously

spell out warnings or codes to the characters.

Early on, when Kathy first visits the hospital, for instance, she walks

across a painted warning on the street: Do Not Enter. She crosses that threshold blindly, and the

horror in her life commences. But she

literally ignores a giant sign, under her feet, warning her to consider her

path.

Later,

the sign at the Roget Clinic which reads “Emergency Entrance” shorts out and comes

to read “Emergency Trance.”

The

pertinent question here is, whose trance is the sign referring to? Is Patrick in a trance, in his comatose

state?

Perhaps

so, but the overall structure of the film suggests that Kathy has lived her

adult life in a trance as well, and that only by breaking out of it (as Patrick

breaks out of his, leaping out of his bed…) can she find happiness, or at least

satisfaction.

Patrick’s

sub-plot about irresponsible science and its prolongation of death, not life,

raises some interesting questions vis-à-vis Kathy as well. She and Dr. Roget

discuss, at length, the point of death, the point at which the soul or

life-force leave the body. Roget also -- using that frog demonstration -- suggests

that a soul may have nothing whatsoever to do with the appearance of life. He report that a simple burst of electricity

mimics the appearance of true life.

Kathy, who has struck out on her own, suffers from an amorphous,

existential problem in the film. She is not satisfied in marriage, or her life

in general. Like that frog (or by extension, Patrick), she has the appearance

of a real life, but it is just a show, a façade.

There’s

a school of thought regarding John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) that

Laurie Strode and Michael Myers are psychologically connected. He is, some say,

a manifestation of her Id, or her “hang-ups” to use a seventies colloquialism. Patrick

rather directly forges a similar dynamic. Kathy and Patrick are both stuck in a

trance, both not really living, both trying to find the spark that can make

existence meaningful. Both find

asymmetric ways to assert independence and power.

Halloween

is a better

horror film, for certain, but Patrick is smart, well-rendered, and

wholly deserving of its reputation as a kind of mini-classic. As I noted above,

the film loses steam some in the third act, and could do with some trimming,

but the clever screenplay, the great central performance by Penhaligon and

Franklin’s crisp, knowing, technically-adroit direction all make the film worth

a re-evaluation.

No comments:

Post a Comment