Supernova (2000) is just the kind of genre film that -- I readily admit -- I’m inclined to enjoy. It involves a doomed space mission skirting the edge of the cosmic map. Specifically, Supernova recounts the most dangerous journey of the Medical Rescue Vehicle Nightingale as -- in response to an emergency signal -- it “jumps” to a rogue moon where a mining outpost, Titan-37, once operated.

Unfortunately,

the Nightingale’s crew learns, post-jump, that the wandering satellite is now

desperately close to a blue giant star, one destined to go supernova in

less-than-a-day.

And

that’s just the beginning of the action.The film also involves an alien

artifact -- a ninth dimensional bomb, -- and a super-strong psychopath, Troy

(Peter Facinelli) determined to keep ownership of the WMD.

Buttressed

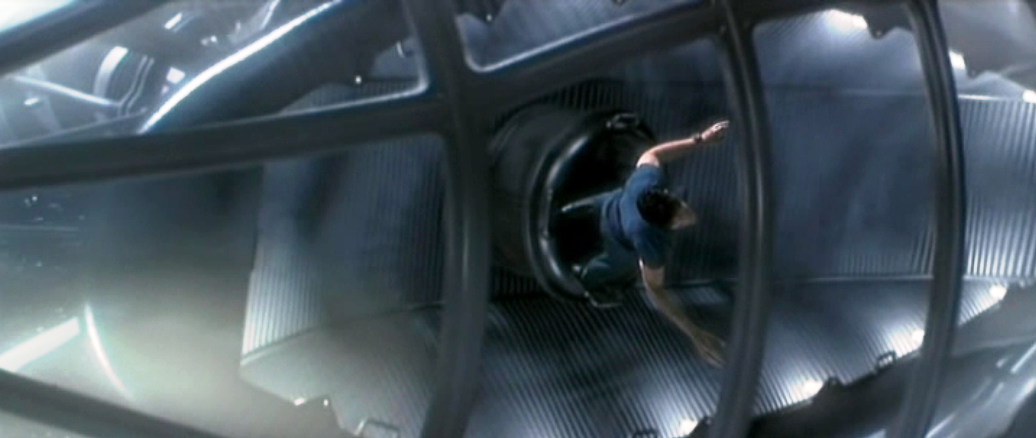

by some solid year 2000 visual special effects, Supernova also features a

promising cast, including James Spader, Angela Bassett, Robin Tunney, Lou

Diamond Phillips, and Robert Forster.

And

yet despite such virtues, this science-fiction film never quite comes together

as powerfully as one might hope it would.

The

action and death scenes are largely run-of-the-mill affairs, less kinetic and

less effective than similar scenes you will find in pictures of this vintage

and type, like Event Horizon (1997) or Pitch Black (2000), for example.

Behind-the-scenes

turmoil on Supernova is the stuff of legend, with director Walter Hill opting

to be credited by the pseudonym “Thomas Lee.” When MGM refused to approve the

budget necessary for special effects, Hill left the production, allegedly, and

Jack Sholder was brought on to complete the film. Then, Francis Ford Coppola attempted to save

the film in the editing process.

Not

good.

Given

a history like that, Supernova is actually a bit more coherent

than one might expect. Legendary box office “bomb” or no, the film boasts a few

facets that even today hold the interest.

The

first is the deliberate aping of the Dead Calm (1989) narrative, which

was writer William Malone’s intent.

The

second quality of value is the film’s steadfast refusal to clear up the

ambiguity of the final act, and the fate that may befall Earth.

Third

and finally, Supernova provides an interesting contrast in “percentages,” in

a subplot that suggests the greatest treasure in the universe may not be

ninth-dimensional matter, but rather the human capability to connect with his

fellow man or woman, right down to the genetic level.

“I

like deep space…People tend to respect your privacy.”

In a few centuries, the rescue ship

Nightingale receives an emergency distress signal from Titan-37, an abandoned

mining operation on a rogue moon.

New to the ship is the co-pilot, Vanzant

(Spader), an ex-junkie who has earned the dislike of the ship’s doctor, Evers

(Bassett), in part because of her personal past with a violent junkie named

Karl Nelson.

After a dangerous jump, the ship’s

captain, Marley (Forster) is mutilated in his bio-protection chamber, and asks

to be killed. And the sender of the

distress call turns out to be the son of Karl Nelson, Troy (Facinelli).

While the ship’s crew tends to repairs from

the dimensional jump, and prepares to escape a nearby blue giant’s supernova,

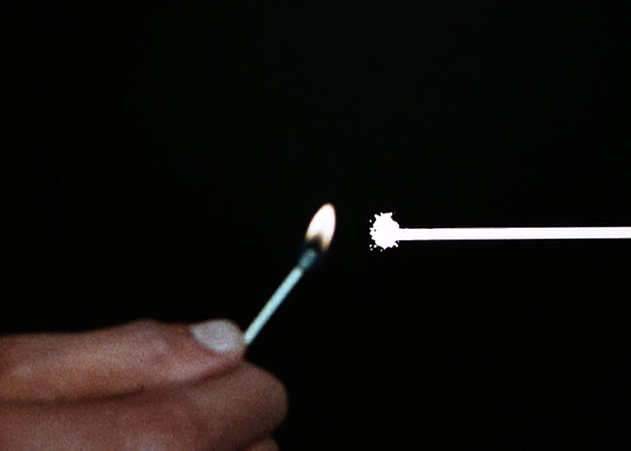

the crew also learns that Troy has in his possession an unstable alien artifact…

“That

whole place is like a ghost ship.”

The

most notable aspect of Supernova’s story, perhaps, is its

dedicated repetition of the plot-points of Philip Noyce’s sea-based thriller, Dead

Calm. In that film, as you may recall, a couple played by Sam Neill and

Nicole Kidman go to sea following the death of their child, only to help out

the last survivor of a ruined vessel, played by Billy Zane. Zane’s character

turns out to be a dangerous psychopath, and he strands Neill’s character on his

useless old boat while he terrorizes Kidman’s character on the family yacht.

In

Supernova,

we also get the passenger from the ruined “other” location, in this case a

moon-based mining operation. The film also finds Spader’s lead character, Vanzant

marooned there, and fighting his way to get back to his ship, much as Neill did

in the earlier picture. Facinelli, like Zane, is a physically-fit, twitchy

psychotic who, before his reign of terror ends, has his way with a female

shipmate. Outer space, obviously, substitutes for the terrestrial high seas.

Supernova

has its problems

to be sure, but the idea behind it, of bringing Dead Calm into the

future, is not one of them. You may recognize the Dead Calm flourishes and

consider them derivative -- because they are -- but Supernova is also original enough to introduce

some new elements to the formula. In this case, it’s the presence of the ultimate

WMD, the alien artifact that elevates the film’s ending. The movie’s denouement,

which eschews our desire for closure, also leaves audiences to ponder what

might could happen in the brave new world following the finale.

There’s

also a present -- if irregularly enunciated -- through-line here about the

human race, or more accurately, human nature. Once rescued by the crew of the

Nightingale, the evil Troy/Karl tries to bring them around to his cause. He

promises them each five percent of the wealth he plans to acquire from the

alien artifact. He prizes monetary wealth, and is surprised that there are no

takers, save for Yerzy.

At

film’s end, uniquely, Vanzant and Dr. Evers are forced to share a biological

containment unit so as to survive the space jump away from the super nova. In

the process, they each swap 2.5 % of their DNA with the other. Add those figures up, and you have 5% percent,

Troy’s proposed figure for recompense.

The

notion here may be, simply, that one “treasure” may be more worthwhile or more

valuable than other. Troy promises material wealth to the crew, but at the risk

of everything, at the risk of the universe itself. By contrast, the biological transfer renders

Evers pregnant, ostensibly with Vanzant’s child.

Who

needs the magic of unstable, 9th dimensional matter, when human

matter can, likewise, “replenish” life, and in a way that is safe?

Finally,

Supernova

ends with a terrifying thought. The shock-wave from the supernova will

detonate the 9th dimensional bomb, and the ensuing shock-wave will

spread out, to all corners of the universe. It will strike Earth in fifty one

years, we are told. When it strikes, it

will either destroy the planet, or change the very nature of human life.

Supernova gives us no idea which outcome is

more likely, or what that change could be. But I’ve got to give the movie

credit for setting up an apocalypse that it never intends to depict, and asking

viewers to consider the possibilities.

Would

the shock-wave render all men and women physically powerful, but mentally

unhinged, like Troy? Or would it usher

in the very “leap in evolution” that

the mad Troy foresees? There are many ways that the movie could have ended. Troy

could have been killed. The ship could have escaped. There could have been a

final sting in the tail/tale. Instead, Supernova leaves audiences to ponder

the idea that a “wave” is coming for mankind, and that it is something he can’t

avoid. The future will be…different.

When

one couples this idea of some force changing man’s physical nature with the

moment early in the film in which Captain Marley (Robert Forster) discusses “violent animation” of the 20th

century (meaning Tom and Jerry), and calling it a “catharsis” that can, under

some circumstances, unleash “human malevolence,” the film’s theme starts to

become clearer.

Tom

and Jerry live in a world in which there are no physical limits or restraints.They

bash, bruise and bludgeon each other with that power, and do almost nothing

else. If the shock wave unshackles man from his biological restraints, will he

find a better use for that power than the animated cat and mouse, his artistic

creations, do?

A

further connection to the film’s leitmotif comes in characterization of the

ship’s computer, Sweetie. The ship’s

navigator, Benjamin (Wilson Cruz) attempts to over-write her programming when

under duress, when threatened with death by Troy.He attempts to unshackle her,

however, so she can kill. Again, there’s the notion here that without

“programming” (or biological) restraints, the universe tends to violence. Man creates Tom and Jerry and Sweetie the

Computer, and directs them both towards such that violence. What chance is there he won’t act violently

if transformed into a superman?

Supernova falters, largely, in that most

of the crew deaths seem to happen all at once, and without tremendous or even

modest distinction. Two crew members, one after the other, get ejected into

space without protection, and die there. Similarly, the battle scenes on Titan

and aboard the Nightingale seem claustrophobic and messy, but not in an

intentional or good way. The scuffles are virtually incoherent, and so some

sense of suspense is sacrificed.

There

are gaps in the storytelling too. Danika Lund is shown to be in an intense (and

apparently rewarding…) romantic relationship with Yerzy. So much so that they

are hoping to be approved as parents when they return home. They want to have a

child together. But after seeing Troy

naked (and with an apparently sizable erection), Danika makes love to him. She

does not seem to be under duress when she does so. She is not executing a strategy (as Nicole

Kidman’s character was, once more, in a similar scene in Dead Calm). Instead, we

have no understanding of why -- besides carnal lust -- she would sacrifice

everything to be with this (admittedly hot…) guy for the right fifteen minutes.

I’m not arguing that people don’t make impulsive decisions about sex all the

time, only that we don’t have a lot of insight into Danika’s character, and her

decisions. Does she feel trapped by Yerzy? Does she really not want children?

Is this her way of avoiding those responsibilities? It would be nice to have just a bit more

clarity in terms of character motivations. If we knew Danika’s reasons, we

might be able to fit them into the film’s larger puzzle or leitmotif. Sex, like violence, might be deemed the

result of our biological programming, and this aspect could have been explored

in the context of the rest of the film’s themes.

It’s

pretty clear that Supernova overcame incredible odds just to get to theaters,

and given the tumult of its production, it’s a little amazing that the film succeeds

to the degree it does. The silver-blue palette that suffuses the film gives it

a sense of visual consistency, and from time to time, the script really gets

close to expressing a meaningful thought about mankind, and what kind of creature

he is, or might become, given a giant leap forward.

It’s

no Sunshine

(2007), Pitch Black, or Event Horizon, but Supernova

occasionally shines very brightly. You

can either enjoy the flashes of ingenuity on their own terms, or curse the general darkness of the enterprise.