Gazing back upon 1983’s TV-movie, Starflight One: The Plane that Couldn’t Land, the most significant question it raises involves timing.

How -- years after the theatrical releases of spoofs such as Airplane (1980) and Airplane II: The Sequel (1982) -- did filmmakers believe they could produce a serious version of the same tired premise that had informed films such as Airport (1970), Airport’ 75 (1975), Airport ’77 (1977) and Concorde: Airport ’79 (1979)?

You remember that premise of the Airport (and Airplane) franchise right? A group of diverse passengers and a stalwart plane crew, including a heroic pilot, are jeopardized mid-flight, by some kind of disaster, whether a terrorist bomb, a design flaw, or a ground attack.

Worse, by 1983, the year of Starflight One's premiere, the disaster film in general had pretty much run its course thanks to theatrical misfires such as Irwin Allen’s The Swarm (1978). Airport ’79 had also proven a giant flop at the box office, failing to earn back, even, its production budget.

Unfortunately, Starflight One: The Plane that Couldn’t Land slavishly resurrects all the tired old character clichés of the Airport films (which were based on the 1968 best seller by Arthur Hailey).

There’s a love-affair going on between a pilot and a passenger (here Lee Majors and Lauren Hutton); there’s an elderly woman on her first plane flight (though not Helen Hayes), and an untrustworthy passenger whose actions jeopardize the survival of the plane (Terry Kiser).

Meanwhile, resourceful personnel on the ground and in the air (here including Hal Linden -- in both places!) struggle to pull a rabbit out of a hat and save the imperiled plane from fiery disaster.

Such roles, through their sheer repetition in the disaster genre, are largely thankless here, and the cast can't do much to make them memorable.

So, who thought Starflight One could have been a good idea, coming along in 1983, at the end of the

Airport and disaster film cycle?

Well, historically speaking, the TV-movie’s premiere in February of 1983 on ABC followed-up on another ABC event of great importance.

Nine months earlier -- in May of 1982 -- ABC had broadcast an extended, three-hour version of Concorde: Airport 79 for sweeps, and it earned big ratings, regardless of its earlier failure at the box office. It ranked in tenth place the week of its airing.

So, to accountants at ABC no doubt, Starflight One seemed like it could plausibly repeat the same magic in the Nielsen ratings.

Add to the mix the special effects creations of Star Wars (1977) guru, John Dykstra, and Starflight One must have seemed like a slam dunk right?

Well, not exactly. The movie finished second in its time-slot, but it was victorious, at least over one of its prime-time competitors: Cocaine: One Man's Seduction (1983).

And artistically? How does Starflight One rank?

Well, to my surprise, there are indeed aspects of this film -- about an hour or so in -- that succeed far better than I expected they would have.

There are, for example two extremely creative and tense “rescue” scenes set in space during the TV-movie's second act. These moments in Starflight One are far more effective than they should be, especially given that so much of the film seems to run on auto-pilot and on tired, stock situations and characters.

These scenes succeed, and more than that, actually qualify as nail-biting. It’s just a shame that the rest of the movie can’t sustain the pace and interest of these inventive sequences.

Instead, one leaves a viewing of Starflight One considering how much, truly, the filmmakers get wrong, particularly about the workings and capabilities of the space shuttle Columbia.

“The eyes of the world will be on Starflight One.”

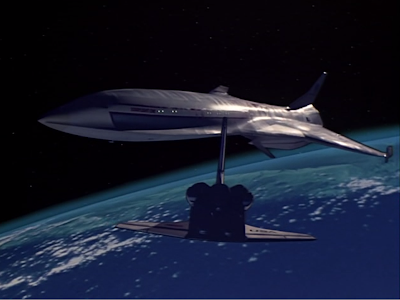

The world's first hypersonic plane -- Thornwell’s Starflight One -- is scheduled for its historic maiden flight from the U.S. to Australia, with pilot Cody Briggs (Lee Majors) at the controls.

Also aboard for the flight are the plane’s designer, Josh Gilliam (Hal Linden), who would prefer the flight be delayed while he irons out some final details, and Brody’s mistress, Erica Hansen (Lauren Hutton).

Other passengers include a man, Freddie Barrett (Terry Kiser), who is attempting to get a new satellite into orbit, and rushing the rocket launch in Australia.

Once Starflight One is in the air, Barrett’s rocket explodes, and debris from it strikes the hypersonic plane. A rocket engine on Starflight One continues to burn, out-of-control -- its instrumentation short-circuited -- and it ascends to orbit…to space itself.

Now, Josh Gilliam must find a way to get the craft back down to Earth.

The problem is that the hypersonic plane possesses no heat shields, and will burn up in re-entry. The shuttle Columbia joins Starflight One in space and makes a handful of dedicated attempts to transfer passengers from the damaged craft to the shuttle.

Meanwhile, Starflight One’s orbit is decaying, and the clock is ticking down towards death and destruction...

“They’re talking. But they’re not saying much.”

Starflight One is mostly slow and rote, with sleepy performances from the likes of Lee Majors and Hal Linden. But in its superior second act, the TV-movie unexpectedly turns riveting for about a half-hour.

Here’s the situation: NASA needs Josh Gilliam (Linden) -- the hypersonic plane’s architect -- on the ground. But he is aboard the plane and must be transferred to the shuttle. Fortunately, the plane is carrying the body of a recently-deceased Australian ambassador in its cargo hold. The bright idea is struck upon that the shuttle astronauts can transfer Gilliam from the plane to the shuttle in the ambassador’s coffin!

As Josh settles into the casket, it is checked for any signs of air leaks and then closed…with him inside.

We see a view of the nervous Josh, inside the sealed coffin, as the transfer across several hundred meters -- in orbit -- is broached. Josh’s fear and discomfort are palpable, and the special effects, which have often been criticized by critics as sub-par, do a good job of revealing the risky and vulnerable nature of this transfer.

Suspense ratchets up to a high-point when Josh detects an air-leak in the coffin, his mode of transport, and realizes that unless he does something soon, he will run out of air before the transfer is complete.

There's a commendable if ghoulish kind of gallows humor about this sequence, especially since it follows another involving the death of a co-pilot in the airlock. One realizes that Josh's transport, his coffin, is an appropriate final resting place, should the mission fail.

The second suspenseful scene in the film is even more disturbing.

With Josh safely on the ground, the decision is made to transfer twenty of the stranded passengers from the hypersonic plane to the space shuttle.

A thin, wobbly “air tube” is connected between the vessels’ airlocks, and five passengers traverse the long, unsteady tunnel at a time. The film shows the audience every step of that long, arduous trip, as the first five passengers make their way successfully across the passageway. Their progress is recorded with a torturous, methodical camera. Again, the desired effect of suspense is achieved.

Then, the second five passengers -- including Kiser’s character and the kindly old lady -- begin making their transfer.

The sparking, damaged hull of Starflight One, however, impacts with the travel tube, and fiery, horrible disaster ensues.

Again, I can give the film no higher compliment than to suggest that it has reached a Poseidon Adventure (1972) threshold of suspense and horror at this juncture. Had I caught this film on TV in '83, when I was thirteen, I would have no doubt been riveted, and the space scenes (and death scenes set in that venue) are not only imaginative, but the stuff of nightmares.

Alas, the last act of Starflight One, including the climactic re-entry scene, fails entirely to live up to the early moments of nail-biting drama and suspense. And, knowing what we do of the space shuttle’s capabilities, the film loses much of its sense of plausibility in the last hour too.

In Starflight One, for instance, the space shuttle launches, meets the hypersonic plane in flight, and brings Josh back to terra firma. Within a 17 hour window, it then re-launches, vets the aforementioned passenger tube debacle, and lands with its five rescued passengers. Then, in the same window of time, it launches a third time, picks-up all remaining passengers inside an empty fuel container, and lands again.

In real life, it would take a shuttle a minimum of two weeks between launches. Here, it makes three journeys in less than a day’s time.

Then, at the end of the film, and quite miraculously, a second shuttle (also bafflingly named Columbia) -- the XU-5 -- appears, already in orbit, and guides Starflight One through safe re-entry.

Basically this second shuttle, of which the audience had no prior knowledge, acts as the heat shield that brings the hypersonic flight home.

Okay, I will buy all that.

But, all the going back and forth with Columbia (on the ground and in space) -- not to mention the death of five passengers and one crew-member -- could have been prevented since the XU-5 was already in orbit.

And since it was already in orbit, why not come up with this safe re-entry gambit right out the gate, five hours earlier?

Many lives (and much rocket fuel...) would have been spared.

Poetic license, I suppose.

Yet when Starflight One was over, I felt that it had all been for nothing. The moments that hooked me were powerful and well-vetted, but buried and suffocated by many routine elements.

Which brings me back to my original point.

It’s really, really difficult to tell this particular story in a serious way, after the likes of Airplane or Airplane II: The Sequel.

Those films are so perfect, so relentless in their chiseling away at the tropes of the disaster/Airport formula, that it’s nearly impossible to take the idea seriously again in their aftermath.

The saddest thing about Starflight One, however, is that, in the moments I described in my review above, the TV-movie actually comes close to climbing that seemingly insurmountable mountain.

In the final analysis, however Starflight One: The Plane that Couldn’t Land is the movie that just couldn’t stick its landing.

I noticed that when Variety reviewed it back in 1983 they commented that it was a 3 hour movie...or, more specifically, a movie in a 3 hour slot with a chunk of that taken out for commercials. The version on DVD etc. appears to be a 103 minute version, and I strongly suspect it's a hacked-down version for theatrical release, which would explain a lot of the very incoherent editing the version I saw. For instance, Robert England's credited in the cast but he's barely visible and I think has no dialog.

ReplyDelete