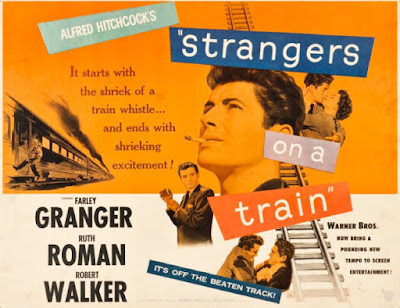

Lives and deaths "crisscross" in master-of-suspense Alfred Hitchcock's taut Strangers on a Train (1951), a classic black-and-white thriller that unfolds like an extended tennis match between evenly matched and opposite contenders.

On one side of the court, we have Guy Haines (Farley Granger), a likable if deadly-serious up-and-coming tennis star. He's unhappily married, and his cheating wife, Miriam (Kasey Rogers) is pregnant with another man's child. Guy wants a divorce so he can escape Miriam, as well as his unhappy life in small-town Metcalf; but also so he can be with his beautiful Washington D.C. girlfriend, Anne Morton (Ruth Roman). She's a Senator's eldest daughter, and Guy wants a career in politics.

On the other side of the court, we have Guy's nemesis, Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker), a flamboyant playboy-type who "sometimes goes too far" in his obsessions (according to his dithering, clueless mother.) Bruno dreams of murdering his overbearing, disapproving father, a wealthy local aristocrat. Anthony is everything Guy is not: frivolous, un-serious, and deeply, deeply unstable. He's also brash, and seemingly unafraid of legal or social consequences for his actions. Life (and death) seems like nothing but a game to Bruno.

The "court" on which these diametrically opposed strangers first meet is, as the film's title announces, a train. To set up the ensuing "match" between these players, Hitchcock determinedly cuts (after views of "crisscrossing" railroad tracks), to opposing shots of the players' feet heading in clashing directions. In fact, it is their feet that make the inaugural contact between the two men, a would-be Larry Craig moment with homo-erotic undertones. The somewhat antiquated British term "cottaging" concerns foot signals among gay or bisexual men indicating sexual desire (often in public places like train stations), so Hitchcock's choice to focus on feet touching in public on a train as mode of initial contact between Guy and Anthony is significant and provocative.

After their feet collide in a train passenger car, Bruno strikes up a probing, flirtatious conversation with Guy. "I have a theory. You should do everything before you die," he says.

Then - aware of Guy's problem with Miriam from the newspaper gossip pages - Bruno offers his theory of the perfect murder. It comes down to this simple plan: two fellows -- with no connection -- meet and swap something...intimate. No, not fluids, but rather murders. It is specifically, as Bruno describes the strategy, a "crisscross." Bruno will murder Miriam for Guy, thus leaving no trail back to Guy for the police to follow. And Guy will murder Anthony's father, doing the same for him. This makes sense because, as Anthony points out, it's always "the motive" that trips up a murderer. In this case, there is no motive.

Weirded out by this overly friendly stranger, Guy excuses himself from Bruno's presence, but Bruno manages to pocket Guy's engraved lighter, which reads: "From A to G." (Meaning from Anne to Guy). As many critics have also pointed out, this inscription might also mean, sub-textually, from Anthony to Guy, another indicator of the under-the-surface, homosexual relationship between the men. Also branded on the cigarette lighter is a significant image: two tennis racquets are "criss-crossed." Just like the lives of these two players.

Bruno then takes it upon himself, without any encouragement from Guy whatsoever, to go forward with his plan; to kill Miriam. Bruno hops a train to Metcalf, and stalks Miriam at a local amusement park. In one clever scene, Bruno boards a boat called "Pluto" and pilots it through the tunnel of love, following Miriam out to an isolated island with her two-would-be-suitors/lovers. The name of the boat, Pluto, is significant since in Roman lore, Pluto was the god of the underworld, one technically associated with the grave or with death. The name of his boat thus associates Bruno with the act of murder. Similarly, the Pluto of myth was a son of the child-eating Saturn/Cronus, a character who symbolizes a domineering father. Again, this is a perfect connection to Bruno, since he desires to purge himself of his father. Like mythic Pluto, Bruno is a vengeful son.

Throughout the scene at the carnival, leading up to the violent strangulation of Miriam, the sexual imagery crafted by Hitchcock proves quite potent. The "loose" Miriam immediately sends non-verbal signals to Bruno that she wants to have sex with him. She seductively licks an ice cream cone, her eyes never leaving Bruno's. In return, he reveals his strength and prowess, wielding a hammer to pound a weight all the way to the top of a marker tower (a clear phallic symbol). Then, in a wickedly edited series of shots equaling foreplay, Hitchcock's camera equates the riding of horses on a merry-go-round with the riding act of intercourse. Bruno, atop one horse, is leaning forward aggressively, in the superior or dominant position. In the very next shot, Miriam (who is shot slightly from behind), seems to be presenting or receiving. These two shots -- in combination -- indicate the desire Miriam and Bruno apparently share.

Finally, as Bruno strangles Miriam, we watch the murder through one lens of Miriam's fallen glasses. Why just one?

Because Strangers on a Train is a story vetted through two perspectives, two worldviews, two lenses. Guy's and Bruno's. Here, in the case of the choking death of Miriam, we are seeing exclusively through Bruno's eyes. It's a view (or vision...) that also comes to haunt him, as he equates eye-glasses with the murderous act he conducted in lover's lane.

Bruno soon ends up at Guy's house in Arlington, and tells him what he's done. Throughout the scene, Guy and Bruno are both positioned (physically) behind the bars of a gate, a visual cue to the possibly consequences of their relationship (prison bars), and an indicator that Guy has become trapped by his "chance" encounter on the train with Bruno. He cannot simply report Bruno to the police for Miriam's murder, because Bruno promises he will name Guy as a co-conspirator. Finally, Bruno gives Guy an ultimatum: kill Bruno's father, or face the consequences. In this section of the film, with Bruno stalking Guy, Hitchcock utilizes another great visual touch that lends new meaning to the tale.

Bruno, in essence, becomes an immovable object. And as we see, an immovable object holds all the power (just like Bruno does). Watch how Bruno is carefully positioned in the frame of several shots. He is absolutely still, unmoving, like a statue. In one extreme long shot, we see Bruno standing silently on the steps of a Federal-style building (between pillars), just watching Guy...from an extreme distance. He is a menace at a distance; a storm-cloud on the horizon. Threatening...

In another shot, Bruno is positioned amongst a large audience watching a tennis match. Everyone in the audience is following the match, except Bruno...who is looking right at Guy. Making eye contact. The "heads" of the audience members ping-pong back and forth comically (left to right; left to right;) avidly tracking the back-and-forth of the tennis match, but Guy is totally and completely still. By keeping Bruno immobile, centered, Hitchcock visually expresses the notion that he is strong, unaffected by what is around him; a singular force to be reckoned with.

And that's exactly the right approach to take, because it is indeed Bruno who now holds all the power in the relationship with Guy. One word from Bruno and Guy is "outed." Fingered. Guy, like Bruno will be labeled a deviant, a criminal. And again, it doesn't take much to understand the sexual or social subtext here. How Guy wants to keep his "relationship" with Bruno a secret, in terms of 1950's social mores and culture.

In the climactic portion of the film, Bruno realizes that Guy will never "follow through" with their relationship (!) and complete the crisscross, killing his father. So, Bruno decides to drop Guy's monogrammed lighter at the scene of the crime (the lover's lane where he killed Miriam) to implicate him. As Bruno hops a train to Metcalf, Hitchcock cuts to an increasingly tense, increasingly fast-cut tennis match between Guy and an opponent. Guy wants to finish off his competitor quickly so he can get to Metcalf and stop Bruno, but there are reverses, surprises and delays.

The entire scene becomes an exercise in generating suspense. Hitchcock perfectly deploys the art of cross-cutting here, and there is one brilliant moment - a surprise - that finds Bruno accidentally dropping the lighter down a grate under a sidewalk. Almost immediately after this stunning accident, the film cuts back to Guy and we hear the words "game, set, match." We think it's over. Fate has intervened on Guy's behalf. But then there's another reverse...a physical feat from Bruno as impressive in dexterity as Guy's tennis. And it's here - watching the ball go from Guy's court to Bruno's and back - that you fully realize how Hitchcock has structured the entire film as a visual tennis match, a fierce competition in which Guy and Bruno hurl the initiative back and forth at one another.

From the tennis match and cross-cutting to the stirring denouement of the film (culminating with an exploding merry-go-round) you will find yourself riveted, unable to look away, unable to disengage or even truly intellectualize what you are seeing. This scene serves as a remarkable example of Hitchcock's oft-noted capacity to play the audience like a piano. The characters have gone from crisscross to deadly, fast-moving circle (as represented by the runaway merry-go-round, spinning in fast motion). That too seems appropriate. At this point the dance between Guy and Bruno (a battle of opposites; a battle of lovers; a battle of doppelgangers, a battle of reflections) is so intricate, so complex, that it can't be untangled. So the two men spin and spin, locked in combat, until the spinning itself can't be sustained either and there's a massive...er...explosion.

Strangers on a Train more than lives up to its reputation as a compelling thriller. Robert Walker is the stand-out in the cast here, portraying an early screen stalker who diabolically straddles the line of charming-obnoxious-creepy without missing a beat. Yet -- as is universally the case when Hitchcock is involved -- the director is the real star of the picture. Hitchcock has cleverly taken the story of two strangers "criss-crossing" and transformed it into something much deeper; and much more disturbing. Murder is the game Anthony plays, one suspects, when he'd rather be playing...something else. After his last bluff, the lighter with those letters on it slips out of Bruno's clutched hand, finally, and the contest of wills is over.

From Anthony to Guy. Game. Set. Match.

No comments:

Post a Comment