John's note: I conducted this interview with comedian Paul Dooley in 2003, while I was researching my book, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company. The subject of the interview was the cult kid's show, The Electric Company.

Interview with Paul Dooley

Paul Dooley may be best-known to contemporary audiences as the cantankerous father-in-law of Larry David on HBO's Curb Your Enthusiasm, or perhaps as a semi-regular in director Christopher Guest's repertory company, in comedies such as Waiting for Guffman (1997) and A Mighty Wind (2003). However, three decades ago, the acclaimed actor, talented improviser, and respected graduate of Second City played another important role: he "turned on" a generation of American kids to the joys and rewards of reading as the head-writer of the PBS education series The Electric Company during its initial season.

Recently, Dooley, who has guest-starred on TV series as diverse as Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (as a Cardassian!), Seinfeld, Tales from the Darkside, Grace Under Fire and Millennium ("The Well Worn Lock"), shared his recollections about The Electric Company, and his behind-the-scenes effort to promote literacy while entertaining the youth of the 1970s.

Muir: How did you come to be involved writing The Electric Company?

Dooley: Well, I didn't know it until years later, but Carl Reiner recommended me for the job. Carl appeared on Sesame Street, as many celebrities did during the first year or two, like my friend, Carol Burnett. They would come on and recite the alphabet or count to ten, just a little short thing they could film in a half-hour and then leave. So when Carl was there, he was asked by the producers if he knew any good writers in New York, because they were trying to put together a new show. He said, 'Paul Dooley's a funny guy, and he lives here.' And I never knew this until the job was over! Twenty-five years later, I finally got to say 'thanks.' I met Carl at a writer's guild screening of a movie and stopped him and said 'I heard you recommended me for The Electric Company years ago.'

Muir: Why do a follow-up TV series to Sesame Street?

Dooley: The producers wanted to address actual reading problems, not just A B C, 1 2 3. They began to realize from Sesame Street that kids were learning from it and wanted more. They were doing it so well after one season of Sesame Street that they had the alphabet; they had their numbers. They also learned things like fairness and morality. The producers started to go further and began to do short words and syllables, and then realized there was a need for another show. Sesame Street was for ages three to six, and our show was from six to nine or ten, just when you are learning to read. Research showed them that this was something that kids were ready for, and could make a difference.

Muir: How did work on the series begin?

Dooley: They had funding of seven million dollars for the first season. They didn't know what would be the title, the format, the cast, or the writing. They didn't know how any of that would work. So they made a decision to have some experimental writing done. They brought in seven writers to work on it, and I was one of them. I thought when they asked me to do it that it was a six week job, and that they got a hold of me because I was known in New York as a writer of radio commercials. I spent a great deal of time in the advertising business right out of Second City. First, I was hired to take copy and make it better. Then I'd spike it up with humor or character or even timing. And after a while I realized they were only paying me as an actor when I was writing the whole thing!

Muir: So your experience in writing and performing in radio ads was a plus on a childrens' show?

Dooley: Well, with children you tend to do short segments because of the attention span, which was why Sesame Street had short pieces, animation and songs. So it was similar to commercials in some important ways.

Muir: So the group of seven began imagining the new series...

Dooley: Well, we all wrote in this kind of limbo for six weeks. Then, at the end of that time, the producers came to me and said they'd like me to sign a contract and be the head writer for the first season and supervise the material and be in charge of the shape of it. Which immediately made the other six guys hate me, because we had been peers. The reason that the producer told me he thought I was the guy to do it was that the other folks had written sketches that just seemed to be in limbo and could be used or not used, and had no cohesion or shape to them. They didn't mean anything in aggregate. But totally unconsciously, what I created was a scene with a character who could be brought back once a week.

Muir: In fact, you created several of that series' most memorable and colorful characters. How did Fargo North, Decoder come about?

Dooley: I have a penchant for names, particularly pun names, so I named a guy Fargo North, Decoder. I was in a meeting with several reading experts who were giving a crash course in reading techniques, and we had to teach reading to the audience, so we had a lot to learn. The experts used a lot of twenty-five dollar words like"encode" for reading and "decode" for reading. So I was sitting next to another writer who was a friend of mine and I wrote in the margin of my notes, "Fargo North, Decoder." Just a little riff, you know. He told the producer about it the next day and he said to me, 'That's a funny idea, let's do something with it.' So I figured he [Fargo] could be a word detective and I kind of based him on Inspector Clouseau, a guy who was tripping over his feet all the time. And then it turned out that almost every sketch I thought of could be used as a running character.

Muir: Tell me about another of your characters, J. Arthur Crank.

Dooley: He was a guy who calls up to complain. I named him J. Arthur Crank based on J. Arthur Rank. And of course, no kid is going to know J. Arthur Rank, and most of their parents - if they were under thirty - weren't going to know him either. But I think it didn't hurt anything, and had a ring to it. And the few people who did hear it and knew Rank would think it was cute. He was a crank caller and instead of just calling him Crank, I called him J. Arthur Crank.

Muir: You've hit on one of the delights of The Electric Company. It was educational and funny for the kids, but there were also little jokes in there that only the adults would get.

Dooley: we did things for the adults that kids might not get, but it didn't cost us anything. The Electric Company had a hip-ness about it. We were told never to look or sound anything like Sesame Street. We didn't want some six-year-old kid to say, 'I'm not going to watch that, that's just like Sesame Street! That's for little kids!'

Muir: You also created a very famous character -- played by the actor Morgan Freeman, before he was a star.

Dooley: Easy Reader. He was based on Easy Rider, but he was a junkie for reading, and that was Morgan Freeman. And the counterpoint of the junkie for reading is the Count on Sesame Street. He could not stop counting. To a fault. So I made a guy who would not stop reading to a fault, and that was Easy Reader.

Muir: Where did the idea come from to call the series The Electric Company?

Dooley: The reason we called it The Electric Company is that the first name we made for it had the word eclectic in it. The producers kept saying that were were going to be very eclectic in our reading techniques, phonics, all these different things, so we would kid around with the word eclectic. Like, 'did you pay the eclectic bill?' And eventually, somehow, we called it The Eclectic Company, and then The Electric Company.

Muir: And the theme song took it from there.

Dooley: Joe Raposa wrote this wonderful opening song. I said 'Let's suppose it is The Electric Company, what would you write? What kind of song would you have? And he wrote some great lyrics. 'We're going to turn you on, we're going to give you the power'...And it was terrific.

Muir: Other elements of the show also utilized the motif of electricity

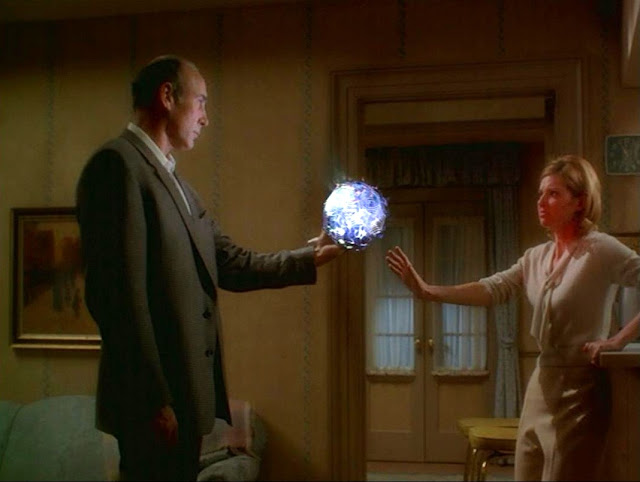

Dooley: A lot of those things I thought of -- like having a hand come in at the end of the show and turn on the light bulb -- because we called it The Electric Company, and that tied it together. I created the line which said: 'Electric Company gets its power from the Children's Television Workshop,' based on Sesame Street, which said things like 'brought to you by the letter A.' I found a bunch of things to hang it on, which made it seem unified.

Muir: Do you ever feel like you've covertly educated a generation?

Dooley: We had this charge that if you make the show entertaining for the parents as well as the kids - if they sit with the kids - not only will the kids learn something about reading, but the parents might learn something they don't know either. Plus, if they sit with the kids, the kids are more likely to watch, and it becomes a family thing.

Muir: You left The Electric Company after one year as head writer...

Dooley: Yes. I worked on the first season and then went back to my real career. I was doing a lot better [financially] when I didn't work for them, because they had a pretty low salary. I was making four or five times as much by working on commercials. I did enjoy it, and it was challenging and rewarding. I said to my wife at the time, 'Finally, I'm doing something with comedy techniques for good instead of evil!'"