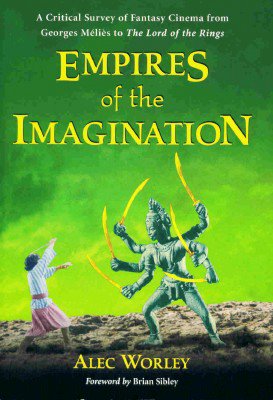

Recently, I had the great pleasure of discovering Empires of the Imagination: A Critical Survey of Fantasy Cinema from Georges Melies to The Lord of the Rings, a new reference book published by McFarland.

Recently, I had the great pleasure of discovering Empires of the Imagination: A Critical Survey of Fantasy Cinema from Georges Melies to The Lord of the Rings, a new reference book published by McFarland. Written by Alec Worley, this book is a scholarly text devoted to the study of fantasy film. I noted in my review of the book for NCFLIX that the author undertook a difficult task, because even the very definition of "fantasy" is not settled. Yet what I discovered upon reading is that Mr. Worley had more than done his homework. In fact, he had worked carefully not only to succinctly define cinematic fantasy, but also provide a fascinating, dispassionate discourse on the subject. Empires of the Imagination is thus a stimulating and worthwhile read (and I recommend it.)

I recently had the opportunity to conduct an interview with Alec Worley on the subject of his book, and fantasy in film.

MUIR: Let's start at the beginning. How and when did you become motivated to write Empires of the Imagination?

WORLEY: Well, I was writing for a British horror magazine called Shivers, and the editor cautiously suggested that we might write a film-book together. He came up with the idea of a book about fantasy films, one that didn't include horror and science-fiction as part of its remit, as is usually the case. The only problem was coming up with a workable definition of fantasy that would encompass everything from The Grinch to Clash of the Titans. So I did a bit of brainstorming myself. Luckily I owned the only three serious books that seemed to exist on the subject (Peter Nicholls' Fantastic Cinema, John Clute and John Grant's Encyclopaedia of Fantasy and David Pringle's The Definitive Illustrated Guide to Fantasy), so I built on what I agreed with from each and came up with a theory that at least made sense to me. I then whaled on it with every argument and example I could think of, trying to tear it apart from every angle. Once I was satisfied the idea was still in one piece and would therefore carry an entire book, I pitched it to David who generously let me run off with it on my own.

MUIR: Let's cover some vital stats. How many films did you ultimately watch to write the book? How long did creating the book take from start to finish? And how difficult was it finding a publisher interested in the topic?

WORLEY: If I didn't have to watch all those movies, if I'd had a heftier reviews file to hand when I started, I probably would have finished the book within a year. But I must have gone through about 600 films or more, and had to be very selective about what I watched since by then I was working to a contract and time was now a factor. In the end it took about three years from start to finish, about one-and-a-half of which I was working nights at a reel assembly plant, splicing together those commercials you see at the start of a movie.

As for the publisher, I'd tried pretty much everyone in the UK, most of whom I'm still waiting to hear back from. The general feeling was the project was too whimsical for the academics and too thoughtful for everyone else. Then I approached editor Stephen Jones (of Best New Horror-fame) at a convention and asked if he could recommend a publisher. He asked if I wanted to make money, or if I wanted a proper book. I sensibly chose the latter and he put me onto McFarland, who have been magnificently supportive and professional throughout the whole thing. I really can't sing their praises enough.

MUIR: Discuss, if you will, some of the reasons why fantasy films as a genre have, for much of their 100 year history, been "ghettoized," as you put it? How has that changed today, or has it?

WORLEY: Fantasy always seems to have been taboo in western culture. In eastern cinema, fantasy has always been regarded as serious subject matter, from Germany's Die Nibelungen to Indian "mythologicals" like DG Phalke's Raja Harischandra. In the west we tend to see the genre more as a vehicle for whimsy, special effects and escapism, although some filmmakers have worked this to their advantage. Soviet filmmakers in the 40s, for example, utilized fairy tale to smuggle political satire past the Communist censors.

Here in the UK, the BBC ran a televised literary survey a few years back called The Big Read, which was won by Lord of the Rings (not surprisingly, since the book had topped a similar contest a few years before, and the publicity machine for the Return of the King movie was in full flight before the final result was televised). The response from the critics just about made my head explode with rage, the utter ignorance of these learned intellectuals as to just what fantasy is, what it can do, and what it has done. For a similar reason I find it difficult to understand Philip Pullman when he says he doesn't write fantasy.

The general consensus here was that fantasy begins and ends with Tolkien, anything like it that's any good has to go by another name. (One critic imaginatively defined His Dark Materials as "metaphysical fabulism.") The idea that fantasy equals mere escapism is crucially - only half the story. Many fantasy narratives begin with a character motivated by a wish to escape the pressures of the real world, but what the hero learns (in intelligent fantasy films like Wizard of Oz and Labyrinth) is that escape from reality is actually impossible. The point of embarking upon fantasy is to return to reality with a change in one's perception, so that you may live more in accord with the irresistible flow of life.

However, with the success of Lord of the Rings and given the response to movies like Narnia and Harry Potter, I believe these will probably only cement the negative view, unless both sides of the court, both fans and critics, achieve some kind of wider recognition of what the genre is and does. Tastes need to broaden on both sides, I think.

MUIR: You discuss the narrative strategies of the fantasy film in the book. Without giving too much away, could you delineate a few of those strategies here for our readers, with an example of each? (I think this is fascinating stuff.)

WORLEY: Well the way I see it fantasy cinema can be placed along a line spanning from documentary realism to avant-garde expressionism (by the way, I make absolutely no claims that literature or oral storytelling can be understood in the same way). It's an idea I borrowed from Louis Gianetti's book Understanding Movies. Basically I would place expressionistic types of story at one end of the scale and realistic stories at the other. As I put it in the book, the closer a film falls towards realism, the more its fantasy elements will be depicted realistically; the closer a film falls towards expressionism, the more its realistic elements will be distorted fantastically.

And here lies the four (well, five really) kinds of fantasy film. At the furthest reaches of expressionism lies pure surrealism (movies such as Bunuel's L'Age d'or), in which reality as we know it holds no more sway than it would in a dream. Fairy Tale (think Edward Scissorhands) sits the next step up towards realism. Here events are organised into a proper narrative but take place in a protean world shaped by the dictates of a God-like storyteller. Sitting dead centre in the realism/expressionism scale there's earthbound fantasy (It's a Wonderful Life), where the worlds of fantasy and reality invade each other. As we move away towards realism the forces of magic (the defining stuff of fantasy itself) becomes regimented more and more by the kinds of laws that affect our own world. Here we find Heroic Fantasy (Conan the Barbarian that's Barbarian, guys, not Destroyer, the crappy sequel everyone mistakes it for). This genre covers the exploits of superheroes like Hercules, Sinbad and Indiana Jones. Lastly, at the furthest reaches of realism, we have Epic Fantasy (Lord of the Rings). This is the most "realistic" breed of fantasy, realistic in that the magic within it is carefully disciplined to create the illusion of a living breathing world.

The theory's rather more involved than this, and there is a great deal of cross-pollination. The Harry Potter movies, for example, are part Fairy Tale, part Earthbound and part Epic. The important thing is not to see this as a set of pigeon holes, rather a sort of "spotter's guide to fantasy motifs," helping viewers and (it would be my fondest wish) writers and filmmakers to identify and understand the genre's components.

It's not about me trying to force my opinion upon everyone else, it's about (hopefully) generating some kind of serious debate on the subject.

MUIR: I thought that "Locating Fantasy" was a brilliant introduction to the book, and that you very carefully and thoughtfully defined fantasy in this section. How difficult was it to come up with that particular definition, and how would you say it eventually came to serve your survey? Were you constantly tweaking, or did you always have a destination in mind?

WORLEY: My definition of fantasy has always been that magic has to be responsible for all the weird stuff in a story as opposed to science. I really donÂ’t mean to be glib, but it's always seemed obvious to me, ever since I was a kid. It was the difference between Jason and the Argonauts and Godzilla. The moment you introduce science into what is essentially a fantasy story you change its entire outlook. Just look at how Lucas destroyed Star Wars with the revelation that the spiritual centre of the original trilogy (the Force) is actually nothing more than a rare blood group. Way to go, George.

Anyway, as I said before, I defined my argument and then tried to beat the crap out of it, reading everything I could, trying to find a chink, trying to contradict my theory. I don't know if you guys are familiar with Blackadder, a historical comedy Richard Curtis and Ben Elton wrote for the BBC in the 80s, but in one episode Robbie Coltrane plays Dr Johnson (author of the first English dictionary), who has a breakdown when someone mentions the word sausage, the one word he forgot to include in his book. Well, a friend of mine dedicated his life to finding what he calls "the Blackadder Sausage," the one example or movie that will bring my argument crashing down. Thankfully, he's still looking.

I wrote the Locating Fantasy chapter first and pretty much didn't touch it again. It was really quite spooky how fluently Empires came together after that, as if the book had already been figured out right down to details I hadn't even thought of, and all I had to do was write it all down.

MUIR: What would you say is your favourite type of fantasy film? In fact, what is your favourite fantasy film and why? Least favourite and why?

WORLEY: Of all the sub-genres I've really got a thing for Heroic Fantasy, probably because it's the most underrated and underexplored. It's the real outlaw of the pack, dealing as it does in the masculine psyche. Writers have done interesting things with this genre, Michael Moorcock's Elric and Pat Mills' Slaine comics for example, but on film the genre hasn't quite got over Robert E. Howard yet. As for individual films, I could go on and on, but I'll give a quick run down. Neil Jordan's Company of Wolves has a weird magic about it that I find endlessly fascinating, along with Jan Svankmajer's Alice and Tony Harrison's Prometheus. I'm a sucker for goth kitsch like Edward Scissorhands, The Crow and The Corpse Bride, although I loathed Tim Burton's Willy Wonka.

Alain Resnais's Last Year in Marienbad and Jean Cocteau's La Belle et la Bete and Orphee are clearly masterpieces, but I'm not sure the're quite loveable enough to be anyone's "favourites." I think Time Bandits (next to Brazil) is probably the best thing Terry Gilliam has ever done. The Golden Voyage is my favourite Sinbad and The Barbarian my favourite Conan. (If only Milius would put together a proper director's cut) There's also a French film I really like called Brotherhood of the Wolf, which in many ways epitomises the sensual texture of Heroic Fantasy.

I cry like a little girl with a skinned knee at Wizard of Oz, A Guy Named Joe, Field of Dreams, Big and Watership Down and for entirely different reasons at Dungeons and Dragons and Ator the Fighting Eagle. Heroic Fantasy also probably has the largest concentration of stinkers, from Thor the Conqueror to The Son of Hercules in The Land of Darkness, movies too dumb to even laugh at. I grew up loving The Neverending Story, but came to loathe it, and the same goes for Ridley Scott's Legend. As for Lord of the Rings I think they're not without flaws (the dwarf jokes are dreadful), but really the very best adaptations we could possibly have hoped for. Considering Hollywood's idea of fantasy at the time of their making was Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, we should be thankful we never ended up with Kevin Sorbo as Aragorn.

MUIR: I notice you comment in the book on the difference between critical analysis and fan boy ardour. Was this a difficult line for you to walk while composing the text? Did personal preference color any of your reviews?

WORLEY: I was completely disciplined on this score. There are too many film-books out there on similar subjects that just gush and reminisce rather than analyse. I want the fantasy genre to be taken seriously, and in order to do that every film had to be looked at with a cold, critical eye, even when that movie was an old friend. I didn't deliberately set out to upset the fan consensus, just give a balanced view and as a result I hope I've given a fresh perspective.

MUIR: Lastly, what's your next project and when can readers look forward to it?

WORLEY: Several irons in several fires at the moment. I'm always guarded about future projects as I don't want to look like a dolt should they never come about. Aside from more film journalism (I've just done a couple of reviews for SFsite.com), I've got some short fiction and several comics projects on the boil (one of them a tribute to Dr Seuss about a flesh-eating zombies) and I'm currently putting some proposals together, one for a film book another for a children's book. Hopefully at least one of them will come to flower next year.

I want to thank Alec Worley for speaking with me on the subject of his book, and film fantasy. I wish him all the best with his future endeavours, and would just like to remind everybody that Empires of the Imagination

No comments:

Post a Comment