The media is reporting the death of Buck Rogers actor Gil Gerard today. Buck (and the talented man who played him so well, from 1979 to 1981) was and will remain one of my great childhood heroes. Today, in honor of Mr. Gerard, I'm reposting a look back the Buck Rogers production that brought the character back to life for the disco era.

The beloved heroic character of Buck Rogers first appeared in the pop culture fifty years before the 1979 television series debuted on NBC TV. Conceived first in comic-strip form by John Flint Dille, and artists Russell Keaton and Rick Yager, "Rogers" became a perennial American fan favorite in 1929. A radio serial about the pilot trapped in a future world was produced in 1932, followed by a series of cinematic cliffhangers starring Buster Crabbe in 1939.

It is fair to say that Buck Rogers, along with Flash Gordon, personified space adventure in the first half of the twentieth-century. Even that was not the end of Buck, however. Ken Dibbs took on the role for ABC television in 1950, in a series of twenty-five minute episodes that aired for a single season. Shot lived, it was limited to small sets and primitive (by today's standards...) special effects.

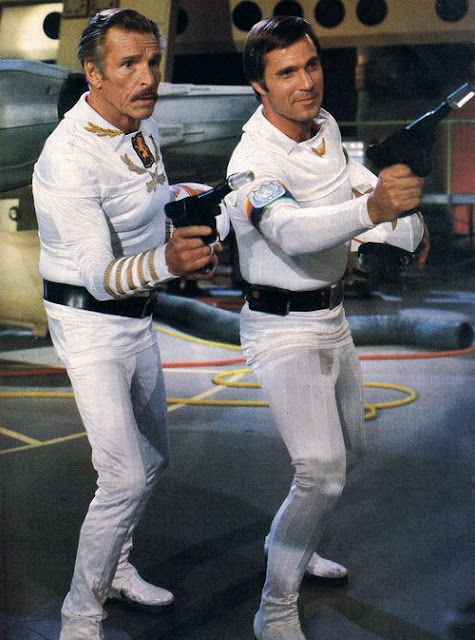

Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, the 1979 series, is Glen A. Larson's second science fiction "opus." It premiered on NBC scarcely a year after Battlestar Galactica bowed on ABC. And like its 1978 compatriot, the first Buck Rogers television pilot played with great success in movie theaters throughout the United States. Starring Gil Gerard and Erin Gray, the series lasted for two years, thirty-six hours in all. It was a moderate success in the ratings during its Thursday night time-slot, slated against the highly-rated Mork and Mindy (ABC).

The 1979 Buck Rogers series was a hip updating that kept all the character names from earlier incarnations, but veered sometimes into tongue-and-cheek, humorous settings. We all know the premise: Astronaut Buck Rogers awakes in 2491 and finds Earth has survived a devastating nuclear war. Vulnerable, the planet is on the verge of annihilation from many alien sources. Pirates regularly attack shipping lanes, and every two-bit dictator in the galaxy has set his sights on conquering the green planet. In this environment of danger, Buck, his "ambuquad"(!) Twiki (voiced by Mel Blanc) and the gorgeous Colonel Deering defend the planet as secret-agent type operatives. In addition to his peerless ability as a starfighter pilot, Buck takes the world of the 25th century by storm with his 20th century wisdom and colloquialisms.

Unlike its somber Galactican counterpart, Buck Rogers was, essentially, a lark, at least to start. It was Mission: Impossible in space, only lighter, and on that basis a tremendous amount of fun. In the first season, the series eschewed morality plays, focusing instead on Buck's "unofficial" missions to bring down galactic criminals.

In "Plot to Kill a City", Rogers disguised himself as a mercenary named Raphael Argus and combated an organization called the Legion of Death, led by Frank Gorshin's Kellog. In "Unchained Woman," he masqueraded as an inmate on Zantia to rescue from a subterranean prison a woman who might finger a crook. In "Cosmic Wiz Kid" - starring Gary Coleman(!) - he rescued a 20th century genius from the hands of mercenary Ray Walston. Through it all, star Gil Gerard seemed the epitome of cool, and decency, and is performance grounded the series, even when the humor threatened to be too much.

This was essentially the pattern for the first 20-something episodes, and in many ways it was a unique formula for the genre on TV at the time. The "caper" was all that mattered. On Buck Rogers, there was no continuing alien menace, although Princess Ardala (Pamela Hensley), Kane (Michael Ansara) and the Draconians showed up occasionally. And unlike Star Trek, there was little or no exploration of new worlds. Instead, Buck was an outer space crime/espionage show. And that meant - that for the first time I'm aware of -- all the conventions of crime and spy television were transposed to the future; to outer space.

On Buck Rogers, this transposition was accomplished with charm and a degree of wit. There were telepathic informants selling their services in "Cosmic Wiz Kid," powerful assassins from "heavy gravity" worlds in "Plot to Kill a City," super-charged athletes looking to defect from dictatorial regimes (the futuristic equivalent of the Kremlin) in "Olympiad," cyborg gun runners in "Return of the Fighting 69th" and a planet conducting a booming slave-trade in "Planet of the Amazon Women.".

However, in one important category, Buck Rogers was a letdown. The outer space battles were competently achieved with the special effects of the day (models; motion-control), but were often badly mis-edited into the proceedings. In the early episode "Planet of the Slave Girls," mercenary ships transformed into Draconian marauders - a noticeably different design - from shot-to-shot. In the same episode, a shuttle on the distant world Vistula launched skyward and passed the matte painting of New Chicago (on Earth), a matte painting that was used EVERY SINGLE WEEK to depict Directorate headquarters. This was the kind of goof that occurred repeatedly. The impression here is of an over-worked special effects department, and an editor with no eye for detail.

Another repetitive and very bad edit concerned the principal spaceship of the show, the very cool-looking starfighter. There were two different designs for this craft, the single and double seaters. Each one had a distinctive and recognizable cockpit design: one slim, one fat. However, the "space" footage of different crafts were often cut together interchangeably within one sequence. In one shot, Buck tooled around space in the single-seater, and in the next, his ship was the impossible-to-miss wider version.

Special effects from Buck's sister series, Battlestar Galactica, were mercilessly plugged into the proceedings too. In "Planet of the Slave Girls," the Cylon base from "Lost Planet of the Gods" substituted for Vistula's launch bay. In "Vegas in Space," "Cosmic Wiz Kid," and many others, the Galactica planet Carillon, seen in "Saga of a Star World," was substituted for the planet of the week. This was achieved in so sloppy a fashion that the Cylon-mined Nova of Madagon, a red star field, was even visible for a few seconds. BG spacecrafts were also brought out of mothballs. The Galactica shuttle doubled as Buck's shuttle in the second season, and ships from Galactica's rag tag fleet showed up in "Planet of the Amazon Women" and "Space Vampire" among others.

Make-up, costumes and props from Galactica also materialized with regularity. The alien "Boray," the focal point of the Galactica episode "The Magnificent Warriors," was seen in the BR episode "Unchained Woman," and Colonial fatigues, also BG hand-me-downs, were utilized as the uniforms for Roderick Zale's henchmen in "Cosmic Wiiz Kid." This oppressive re-use of Galactica equipment, effects, make-up and sets, along with the frequent editing glitches, often made the future depicted in Buck Rogers appear cobbled-together, cheap or just unimpressive.

Story-wise, Buck Rogers also rehashed identical plot elements in tale after tale. A spy in the Directorate might have made an effective plot development in one or two episodes. However, different spies in Huer's HQ showed up in "Planet of the Slave Girls," "Plot to Kill A City," "Return of the Fighting 69th," and "Unchained Woman," episodes 2, 4, 5, and 6 of the series!

There was also the embarrassing overuse of what this author calls the goofy drug. This was a chemical compound that, when injected into suspects, made them look like a total goofball, stoned and "groovy" feeling.

Buck received the goofy drug twice in "Awakenings," and once in "Cosmic Wiz Kid." He used it on a thug in "Vegas in Space," and Wilma utilized it on Quince in "Polot to Kill a City" and then again on Mykos in "Olympiad." This drug was a truth serum, and interesting to see deployed, but six times in less than two-dozen episodes may have been too much.

After its first year on the air, Buck Rogers underwent dramatic changes. Gil Gerard and Erin Gray were both apparently unhappy with the less-than-substantive storylines. In an interview with Starlog, Gerard confided that he'd re-written virtually every episode of the first year, sometimes on-set, to make terrible stories passable. As a result of his disenchantment, a new format was devised. Dr. Huer, the Defense Directorate, Dr. Theopolis and the Draconians were axed. Buck, Wilma and Twiki became crew-members aboard a starship called the Searcher (really the redressed cruise ship from "Cruise Ship to the Stars.") The Searcher's mission was to locate the "lost tribes" of Earth, men who were believed to have fled the planet sometime after the nuclear holocaust of the late 20th century.

But let’s revisit the premiere episode.

Buck Rogers in the 25th Century -- though designed as a TV series -- actually had its premiere in American movie theaters on March 30th, 1979.

The film, originally a pilot called "Awakening" quickly provided a remarkable return on Universal’s investment. It was produced for a little over three million dollars (or one-third of Star Wars’ budget, essentially, in 1977) and the movie grossed over twenty-one million dollars in American theaters alone.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, the film was generally well-received by critics, despite its TV origins. Vincent Canby at The New York Times belittled the film as “corn flakes” while simultaneously comparing it to the big boys: Star Wars and Superman: The Movie. He also noted (with grudging admiration) the ingenuity of the film’s makers.

I remember seeing Buck Rogers in the 25th Century in theaters and enjoying it tremendously, unaware that it had been conceived and shot as a TV series pilot and then kind of exploded into becoming a full-fledged feature film. In 1979, the special effects held up on the big screen beautifully (particularly the moments in Anarchia, a ruined 20th century city inhabited by mutants…), and the film, overall, was a lot of fun.

Today, however, it is not difficult to detect some of the “growing pains” of this production as it stretched from being, essentially, a kid-friendly TV pilot to a more adult-oriented,“big” event movie. What began as a relatively straight space adventure inched closer to a nifty and ingenious paradigm: James Bond in Space.

This shift in premises is best exemplified by an opening credits sequence which features Buck romancing scantily-clad women of the 25th Century, who pose and preen on the over-sized letters of his “name” while a Bond-like ballad blares on the soundtrack. It’s a little bit ridiculous, and a little bit cheesy, but it definitely captures the 007 aesthetic: sexy women and a catchy pop-tune.

|

The Women of James Bond Buck Rogers. |

Thus sexual double-entendres were ham-handedly added to the production when the shift in venues was broached. Other double-entendres work a little better than this one because they arrive via the auspices of ADR or looping, and therefore we don’t get the chance to visually note the inconsistencies.

Another not-entirely successful addition to the original pilot sees Buck going mano-a-mano with Tigerman, Princess Ardala’s hulking bodyguard and the film’s equivalent of Oddjob, or Jaws…a so-called soldier villain. There’s nothing wrong with the climactic physical confrontation between Buck and Tigerman, except that Buck faces a different Tigerman here, not the one seen throughout the film. This discontinuity is left unexplained, but Derek Butler plays the character throughout the film, and H.B. Haggerty (who returned to the role in “Escape from Wedded Bliss” and “Ardala Returns”) plays him for the fight sequence. The two men are both imposing, but boast very different looks in terms of muscle-mass and body-type. Honestly, I didn’t notice the substitution as a kid, but the switch is impossible to miss now.

|

Tigerman #1 (Derek Butler)

|

|

| Tigerman #2 (H.B. Haggerty) |

These last minute additions to the enterprise feel somewhat jarring, even if they add to the James Bond mystique of the thing. A more significant problem, however, involves the thematic approach to the material. Buck -- in both the film and the series – is raised up as some kind of paradigm for Earth’s future, the ideal man. A professor and friend at Hampden-Sydney College called the idea “American Exceptionalism in Space,” and he was right.

The only problem, of course, is that Buck is from the very age on Earth that brought about the devastating nuclear holocaust. His generation, in essence, destroyed everything. It seems strange and counter-intuitive, then, to deride the sincere 25th Century folks -- just climbing out of a five hundred year economic and cultural hole, as it were – for depending on computers, since the episode makes plain the notion that ungoverned emotions and passions were what brought about the end of 20th century mankind. These benevolent robots, acting dispassionately but helpfully, instead rely on logic and rationality. As Dr. Huer notes, they saved the Earth from "certain doom" and have been "taking care of areas where we made mistakes, like the environment."

So…would you really want to go back to the approach that led to Earth’s ruin? Would you life Buck up as a role model, or see him as a backward man from a much more primitive time?

It would be one thing if the movie noted that some balance between approaches -- logic and emotion -- needed to be struck. But the 25th century characters are treated, in broad strokes, as gullible fools who can’t even pilot their own star-fighters (even though those ships are built with very prominent joy-sticks designed for manual control).

It’s all a little bit…incoherent. Yet the film gets away with it because, again, of the James Bond comparison. We all know that James Bond is irresistible to all women, best in a fight or shoot-out, and supreme exemplar of style and taste. Nobody does it better, right? Here, Buck Rogers seems to have the same magic touch. We accept the premise, in short, because we recognize it from that other franchise.

Despite such flaws, the movie vets an intriguing premise involving the Draconian “stealth” attack (a kind of Trojan Horse in Space dynamic), and features at least one authentically great sequence set in Anarchia, or “Old Chicago.” Here, Buck goes in search of his past, and finds it…in a grave-yard.

This scene in Anarchia is particularly well-shot, acted, and scored, and adds a significant human dimension to the film’s tapestry. We are reminded that Buck has lost everything. Not just his family…but the world he knew. Here, Buck Rogers harks back to a 1970s movie tradition earlier than Star Wars: the dystopia or post-apocalyptic setting of such efforts as The Omega Man, Logan's Run or Beneath the Planet of the Apes. I’ve always wished that the ensuing TV series had followed up on this plot-line a little more sincerely. There were many stories to be vetted in Anarchia, but in its two-year run, Buck never returned there (that we know of).

I should add, the special effects visualizations of New Chicago and Anarchia are nothing less-than-spectacular, even today. Again, it’s difficult to reckon with just how cheaply this movie was made because it features extensive, highly-detailed matte paintings, numerous space dogfights, and huge sets (like Ardala’s throne room…replete with Olympic-size swimming pool).

Finally, I would be remiss without mentioning Buck Rogers’ other great “visual.” Vincent Canby writes: “Pamela Hensley is the film's most magnificent special effect as the wicked, lusty Princess Ardala, a tall, fantastically built woman who dresses in jewelry that functions as clothes and walks as if every floor were a burlesque runway.”

There’s probably a case to made that Hensley is one of the Best Bond Femme Fatales ever…except that she’s not technically in a Bond film, of course. Still, the material is close enough, and boy does she have a sense of…presence. I can't think of many actresses who could pull-off that "boogie" scene with Buck Rogers here. But Hensley disco dances with the best of them, retains her character's regal sense of dignity, and is awfully sexy...

|

| Pamela Hensley as Princess Ardala |

I can’t really argue that Buck Rogers in the 25th Century is in the same artistic class as contemporaries like Star Wars or Superman: The Movie. But the movie is undeniably fun, and it sets up – with tremendous entertainment value -- the boundaries of Buck Roger’s new life in the 25th Century. In other words, it’s a pretty great TV pilot for 1979 even if -- blown-up to the silver screen – it all plays as a bit scattershot.