One

night, a lone stranger washes up, unconscious, on the shore in California, and

is rushed to a hospital.

However,

all conventional treatments fail to save this green-eyed young man with webbed

fingers.

Scientist and oceanographer Dr. Elizabeth Merrill (Belinda J.

Montgomery) realizes that his lungs are “desiccated”

and that he is a water breather by nature, one only “marginally equipped” for life on land.

The

young man, soon named Mark Harris (Patrick Duffy) is taken into custody at the

Naval Undersea Center and studied there by Merrill. She learns he is “perfectly adapted to aquatic life” and

that though his skin appears human, it actually possesses “dolphin” qualities.

Mark,

who can survive water pressure at 30,000 feet can outrace swimming dolphin and

jump 20 feet into the air as well. Psychologically, he is “cool and calm.” If

he possesses emotions at all, he seems to “conceal

them.”

Soon

Mark begins to resent his captivity, but Admiral Pierce explains to him the

concept of defense of country. Still, Mark, who is an amnesiac, is not at certain he wants anything to do with the surface world.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth learns, from a Navy computer, that Mark may be “the last citizen of Atlantis,” the

mythical undersea kingdom believed sunken.

When

three American submarines disappear in a “dangerous part of the world,” Mark --

a self-described “citizen of the ocean”

-- goes to investigate. To everyone’s

surprise, he discovers some 36,000 feet down a “sea mountain habitat.”

There,

a man named Mr. Schubert (Victor Buono), formerly a sea-going junkman, is

planning to start World War III, and working to develop a homo aquatic…a being truly at peace with the sea.

He realizes Mark holds the key to making that

dream a reality…

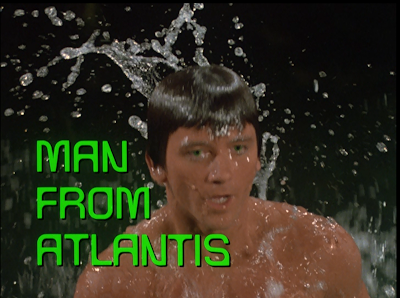

The

Man from Atlantis

(1977-1978) starts right here, with this TV movie from the spring of 1977. Man from Atlantis was written and

created by playwright Mayo Simon, and produced by Herb Solow, who --

while he was at Desilu in the 1960s -- also worked on Mission: Impossible (1966-1973)

and Star

Trek (1966-1969).

The first TV movie is directed by Lee H. Katzin (1935-2002), who directed not only

episodes of Mission: Impossible, but who launched Space: 1999 (1975-1977) as

well with his work on “Breakaway” and “Black Sun.”

The

quality that makes Man from Atlantis

so compelling, even nearly 40 years later, is mystery. The premise is practically irresistible.

A

man with no memory -- not to mention a series of strange biological aberrations

-- washes up on the beach after a terrible storm. From this point forward, the story involves

Mark Harris’s efforts to “discover” himself. It’s a journey that the audience

enthusiastically pursues with him, and with smart, sympathetic scientist, Dr.

Elizabeth Merrill.

Mark

Harris is part of a particular “school” of sci-fi and horror characters. He is

physically superior to all those around him, and yet, by the same token, is an individual marked

as different, or as an outsider. He is

alone in a very real sense, since his emotional states are different than ours,

and he is marked -- with piercing green eyes and webbed fingers -- as not quite

human.

The

genre returns to this brand of character again and again, in decade after decade, because

he or she tends to be very appealing as social gadfly. Mr.

Spock (Leonard Nimoy) on Star Trek in the late sixties is one

example of a physically superior outsider who, because of his status, can

comment effectively on the human world.

Barnabas Collins (Jonathan Frid) in Dark Shadows (1966-1971) is another

example, though one geared more to the “dark side” of the equation.

An

extremely fit (and young) Patrick Duffy essays the role of Mark Harris here,

and throughout the franchise, to remarkable effect.

Mark Harris's innocence and naïve nature

never feel forced and artificial, and yet (unlike Spock), he doesn’t look down

his nose at humans. It is clear that Mar

is both fascinated and confused by the human race. At the TV-movie’s end, he

notes that he will remain in the human world (although he has been a captive of

the Navy, essentially…) because he still has more to learn, both about himself

and the people who inhabit dry land. “I

have not learned enough,” he declares.

And

yet while he wants to learn more, Mark is admittedly baffled. “Explain feelings,”

he demands at one point. “I don’t know if I can,”

replies Elizabeth. Mark is thus a cold

fish, but a cold fish whose interest in humanity has been piqued.

Much

of the humor in Man from Atlantis arises from the (literal…) fish out of water

premise. Mark doesn’t understand human emotions, behavior, or even language. He

questions everything, including humanity’s sense of morality. He is therefore a

perfect character to reflect on mankind, and the species’ treatment of the

environment (particularly the oceans), and those who are different.

The

production values are sterling in this original telefilm. Schubert’s underwater

base and submarine (which is later re-purposed as the Cetacean...) are beautiful

miniatures (created by Glen Warren Productions) and the sets for the interior

of the same base are downright Bond-ian in size and spectacle.

The production also had the assistance and participation of the U.S.

Navy, and there are scenes set here on the decks of real ships, which lends verisimilitude to the proceedings.

Thematically,

the story succeeds because of the profound philosophical differences represented

by the hero and the villain. Mark is a

person who wants to “learn” more about the world, and understand.

Schubert, by contrast, wants to burn it all

down, seeing the status quo as hopeless. “We’re going to shake our planet back to its

roots,” he says. Schubert also insists that

there’s no “hope left but to start all over again.”

Sadly, this "burn it down" approach has a corollary in real life politics. There are those who espouse anger and destruction, rather than building on the basis of our successes.

This plot is very similar to that of The

Spy Who Loved Me (1977), which premiered the same year as Man from

Atlantis, and featured a villain with webbed fingers, Stromberg, and his desire

to destroy the world and start fresh under the sea.

In this case however, we do get that

significant yin/yang, which makes all the difference; that opposition of innocence (Mark Harris) and cynicism

(Schubert). That symmetry lends artistic

depth and interest to Man from Atlantis.

There

are some strange 1970s moments in Man from Atlantis, like the Navy computer’s

omniscient declarative statement that Mark must be the last citizen of

Atlantis.

And certainly, one can look at the series as an attempt to mimic the

then-popular Six Million Dollar Man (1973-1978) or The Bionic Woman

(1976-1978). Like those series, Man from Atlantis is about a person

of unique abilities and senses working in tandem with the United States

Government to stamp out national and international threats. In the pilot for The Six Million Dollar Man and in this first TV-movie of Man from Atlantis, there are training scenes, for instance, which diagram the breadth of the special individual's abilities. Mark races a dolphin, for instance.

Yet at its best, Man from Atlantis, by

highlighting Mark’s outsider status, proves a solid vehicle for social commentary; for exploring man’s relationship with man, and with his planet.

The

series that followed this superbly-crafted television movie did not always live

up to that task, however.

Next

up: “The Death Scouts.”

No comments:

Post a Comment