Submitted for your approval… a genre movie from the year 1983 which confirms the old adage, “you can’t go home again.”

Case in point: Twilight Zone: The Movie, a big-budget anthology directed by the best of the Brat Generation Hollywood directors: John Landis (An American Werewolf in London [1981]), Steven Spielberg (E.T. [1982]), Joe Dante (The Howling [1981]) and George Miller (The Road Warrior [1982]).

All these talented directors grew up with tremendous affection for Rod Serling’s landmark fantasy/horror anthology, which aired on CBS TV from 1959-1964. That these directors were well-intentioned is unquestioned. But the cinematic results are perhaps not quite what audiences hoped for.

In part, of course, the film’s reputation has been sullied by a terrible accident.

During filming of the movie’s first segment, directed by John Landis, lead actor Vic Morrow and two child actors were killed in a tragic helicopter accident. The filmmakers were then tried for negligence and eventually exonerated in a very well-publicized trial. But the bottom line is that Twilight Zone: The Movie -- and especially that first tale -- are simply not enterprises worth dying over. That two of the deaths involved children makes the matter even more gruesome and sickening.

Outside of the unforeseen circumstances of the notorious and fatal accident, Twilight Zone: The Movie suffers from a crucial strategic mistake. It remakes three very strong episodes from the television series, and in doing so fails to improve on them. Now, some people might insist that a movie and television series are surely apples and oranges, so why compare? The answer is that one quality of good criticism is, indeed, the ability to meaningfully compare and contrast works of art. In this case, the movie rewrites of the three original TV teleplays are simply inferior to the originals. This is the case in terms of writing, characterization, and heart, if not in terms of monetary resources.

This is not to state that all the remakes are utter failures. “Kick the Can” is a dramatic failure along with the first story, “Time Out,” but “It’s a Good Life” and “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” are entertaining and intriguing efforts…just not up to the (admittedly-high) standard set by the TV series.

The underlying question here is this: Why would three inventive directors remake (and not faithfully, either) three stories already told and so well-known, veritably inviting such invidious comparisons?

Why didn’t these directors at least attempt to offer something new and fresh? In 1983, Twilight Zone fans had already seen more than enough reruns, after all. And it’s hard to see the appeal of reruns that -- though boasting bigger budgets -- don’t tell the stories as ably.

Featuring two very weak stories, and two decent ones -- with an excellent wraparound narrative device, featuring Albert Brooks and Dan Aykroyd also thrown into the equation) -- Twilight Zone: The Movie is a mixed bag indeed, and one that demonstrate, if nothing else, just how remarkable Rod Serling’s original series truly was. The movie never feels like much more than a Cliffnotes version of the Twilight Zone, read aloud, as it were, by some very ingenious directors.

“Wanna see something really scary?”

In the realm called the Twilight Zone -- a land of shadow and substance, of things and ideas -- four fantastic stories unfold.

In the first, Bill (Vic Morrow) is a bigot who gets a taste of his own hateful medicine when he becomes a Jew in Nazi Germany, an African American at a KKK rally in the South of the 1950s, and a “gook” under attack by American armed forces during the Vietnam War. In the end, he is carted off to a concentration camp, with no hope for reprieve…

In the second story, kindly old Mr. Bloom (Scatman Crothers) brings vitality and joy to the residents of Sunnyvale Retirement home with a magical game of Kick the Can. The old folks are transformed into children, but then Mr. Bloom cajoles them into returning to their older bodies.

During the third story, “It’s a Good Life,” teacher Helen Foley (Kathleen Quinlan) meets an unusual child named Anthony (Jeremy Licht), who can re-shape reality to his will. But all he wants is a family that really loves him. Helen, realizing that Anthony needs a loving but strong influence in his life, takes him under wing.

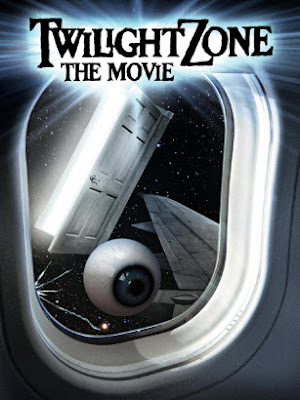

And finally, a nervous flyer named John Valentine (John Lithgow) spots a terrifying creature – a hideous gremlin-- on the wing of the airliner while in flight (and during a storm to boot).

“Time Out”

First and foremost, Twilight Zone: The Movie may serve as a reminder that a big budget and big name directors don’t necessarily ensure superior quality. The fact of the matter is that the three remakes feared here, while of variable quality, are universally less-successful than the episodes on which they are based.

But the original story, “Time Out” is an unmitigated disaster. I write that, by the way, as an affirmed admirer of John Landis’s great An American Werewolf in London.

But “Time Out” is a mindless runaround filled with explosions, chases and battles, but little humanity and little understanding of humanity. Worse, it boasts no sense of proportion and no sense of the Twilight Zone’s essentially just nature.

Here, William Connor is a man with “a chip the size of the national debt” on his shoulder, a man who seems to possess a blind hatred for all non-whites. In the story, he goes to a bar, meets some friends, and immediately rails (loudly…) against Jews, Arabs, and African-Americans. There’s no doubt he’s a big mouth, and an unlikeable fellow. As I wrote in Horror Films of the 1980s, once you meet William Connor, you want to shut him up with a punch to the mouth.

But had this story been vetted by someone like Rod Serling, however, Connor might have faced a different excursion to the Zone. Perhaps he would have awakened one morning to find himself in the body of an African-American. Throughout his day, he would have then been confronted head-on with racist behavior of all forms, both overt and subtle. By experiencing the reality of racism -- by living in the shoes of another human being -- Connor would have learn something about human nature, and perhaps have come to see the error of his ways.

But none of that happens here. Instead, Connor gets carted off to Nazi Germany, where he is chased. Then he ends up in 1950s Alabama, at a rally for the Klan…and is chased. And then he ends up in the swamps of Vietnam…and is chased again, until an explosion somehow blows him back to Nazi Germany and he is captured.

Then, he ends up in a death train, bound for a concentration camp. The story ends with no hope, no rescue, and, importantly, no learning on his part about what he did wrong.

Not only is the accent on action and explosions absolutely wrong for The Twilight Zone, but the punishment doesn’t fit the crime. Connor talks a big show, but he never sets out to physically harm anyone in the story. He’s a bully and a loud mouth, certainly, but does he deserve to die in the concentration camps because he is a big-mouth bigot?

Death camps were wrong on any and every level imaginable -- a testament to our cruelty as a species -- and the people who died in them didn’t deserve such a fate, either. But as thinking and moral human beings, we can recognize that nobody, not even a bigot, should die in one simply because he used ugly words.

It’s a very severe punishment for diarrhea of the mouth. I submit Bill could have been better taught a lesson about his racist views in a more pro-human, social way. As it stands, what’s the moral upshot of the climax?

Well, that’s one less bigot in the world! Woo-hoo!

Basically, everything that could be wrong with this particular story is wrong. Connor goes to his death over speaking (loathsome) racial slurs, and is thus denied the opportunity to learn why he was wrong to use them. On TV, The Twilight Zone rarely seemed this draconian. There, the punishment would largely fit the crime, which is something you can’t say of this empty action tale.

If you look back at Twilight Zone stories such as “The Encounter,” you can see how Serling took on racism in a less two-dimensional style. In that particular tale, a young Japanese man (George Takei) and an American World War II veteran viewed each other with distrust and dislike because of the war experience, for instance. “I am the Night, Color Me Black,” also looked at institutionalized racism in the South, and how it is an affront not just to the law, but to God.

Both of those stories reveal more depth and heart than “Time Out.”

“Kick in the Can”

Alas, Steven Spielberg’s sentimental “Kick the Can” is not much better than “Time Out.”

Here, a group of cuddly old people -- virtually all of them Jewish stereotypes -- are magically granted the opportunity to be children again when a kindly stranger brings a night of magic to their dreary nursing home.

In the original episode that aired on television, one of the old folks at the home came up with the idea himself that he had grown old because he had stopped playing. To play, he insisted, was to be young.

Thus in the TV version, the magic arose from within the residents of the home themselves as they re-

connected with their inner children. It was a beautiful and heart-wrenching tale about how growing old isn’t just a quality of the body, a physical thing, but a mental thing too. And it’s never too late to recapture that youth; to play. You just have to find the child within. You just have to remember what it is to be young.

Such noble and affirming ideas are lost in Twilight Zone: The Movie because Scatman Crothers plays a wandering magician who generously bestows youth on others, whether they ask for it or not. Suddenly, the quality of youth is not an internal one, a quality that can be “activated” by one and all. Instead, it is the magic pixie dust of a wandering Peter Pan, doled out like candy, and then taken back.

Indeed, Mr. Bloom’s whole modus operandi is extremely bizarre. He urges the old folks to play kick the can and experience youth, and then, once they are transformed into children again, urges them to go back to their old bodies. In other words, he’s forces them to dance to his tune, to learn what he wants them to, and, then, even draw the same conclusion he has drawn.

These poor old folk really get jerked around, but the important thing is that the discovery process of “being young at heart” is lost. These old folks are denied the learning they were afforded in the TV program, and so the message gets lost, or at least muddled.

Frankly, it’s a mystery why the original TV script wasn’t deployed here, instead of an inferior knock-off that misses the point. In terms of visualization, the story looks muddy, a mélange of browns and gold -- no doubt to suggest the autumn of life. And the camera work features an unfortunate, claustrophobic quality that is never relieved, even when the senior citizens are made young again.

“It’s a Good Life”

Joe Dante’s installment, “It’s a Good Life” is a huge step-up in terms of quality, yet it also can’t quite stand-up to the powerful memory of the TV episode, which featured Bill Mumy as an over-indulged, super-powerful kid who could wish people “into the cornfield.”

There, in that TV version, the horror dwelt in the suggestion of what horrible things Anthony might do. A man who dared to challenge the boy was turned into a springing jack-in-the-box, for instance, but it was seen only in creepy, imagination-provoking silhouette.

Here, director Joe Dante goes full-throttle into cartoon mayhem, creating Looney Tunes-styled nightmares to threaten teacher Helen Foley (Kathleen Quinlan) and Anthony’s family. But where the TV story concerned an indulged child who thrived because people refused to draw limits, the movie version is a special effects freak show about a lonely kid who creates monsters – wait for it -- to be loved.

Two problems with this approach: First, Anthony’s family is depicted as being bad…as though it is somehow at fault for being afraid of him and his monstrous creations. And secondly, Anthony does horrible things (like disintegrating one sister’s mouth, and consigning another to cartoon hell…) and we are supposed to forgive him -- feel sorry for him -- because he is so lonely and unloved.

He may indeed be lonely and unloved and therefore deserving of sympathy, but that doesn’t excuse the way he tortures his family.

And the story’s ending is pure sentimentality and fantasy land: Anthony and his new “Mom,” Helen, drive off into the metaphorical sunset as sweet, fantasy flowers suddenly bloom, dotting the landscape.

Just wait until that kid is a teenager, Helen, and then let’s see how you do with little Anthony…

Like “Kick the Can,” “It’s a Good Life” loses the emotional and narrative meat of the televised story, and replaces that meat with lesser…confections. The special effects are great, for instance, and the cartoon world absolutely unnerving, not to mention original. As a fan of Heckyl and Jeckyl, I love how Dante uses that old series’ episode “The Power of Thought” to reflect Anthony’s ability to recreate the world, as if it too is a cartoon.

There’s good stuff here, absolutely, and the visuals are dazzling enough to gloss over the narrative and character deficits. But those deficits do exist, and occasionally come through.

For instance, we are never quite sure what Helen is thinking when she agrees to take over parental responsibilities for Anthony. Does she see his powers as a tool she can wield? Or is she pure of heart, and wishing only to help a lonely child? Helen remains such an undeveloped character that her motives stay opaque

.

“Nightmare at 20,000 Feet.”

“Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” ends the movie on fine horror footing. Here, a twitchy, over-the-top John Lithgow battles a fierce gremlin on the wing of a plane in flight.

Director George Miller adopts claustrophobic framing and cockeyed-angles so as to make us feel the breadth of Lithgow’s panic. He succeeds well in making the jet feel more like a flying coffin than you average-every day conveyance. In presentation and form, this episode is truly scary, even a tour de force in terms of style. A perfect ending story, it is dominated by electric jolts and a strong sense of menace.

But again, the original version’s subtlety is missed. The episode, directed by Richard Donner, involved a man, played by William Shatner, recovering from a nervous breakdown. Because of the man’s history, there was a tension in the episode between what people expected of him, and how he reported what he saw.

In other words, he was a man desperately trying to hold onto his dignity at the same time that he battled an impossible creature from the Twilight Zone.

In the movie, that tension is gone, because Valentine just happens to be a very nervous flyer. Nobody knows him, and he has no history of crying wolf, so-to-speak.

Clearly, this is the best segment in the film, and it gets by largely on directorial legerdemain. And that gremlin is scary as hell, a notable improvement on the fluffy gremlin of the TV series.

A crucial part of my 1983 summer of fan discontent – along with Return of the Jedi and Superman III -- Twilight Zone: The Movie is slicker and more manipulative than any tale Rod Serling ever imagined, yet also less clever, less soulful, and less terrifying too.

This Twilight Zone movie is more “shadow” and less “substance” than the TV series provided on a weekly basis for five years.

John, insightful review for a memorable 1983 movie. SGB

ReplyDelete