Creator of the award-winning web series, Abnormal Fixation. One of the horror genre's "most widely read critics" (Rue Morgue # 68), "an accomplished film journalist" (Comic Buyer's Guide #1535), and the award-winning author of Horror Films of the 1980s (2007) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002), John Kenneth Muir, presents his blog on film, television and nostalgia, named one of the Top 100 Film Studies Blog on the Net.

Tuesday, September 30, 2025

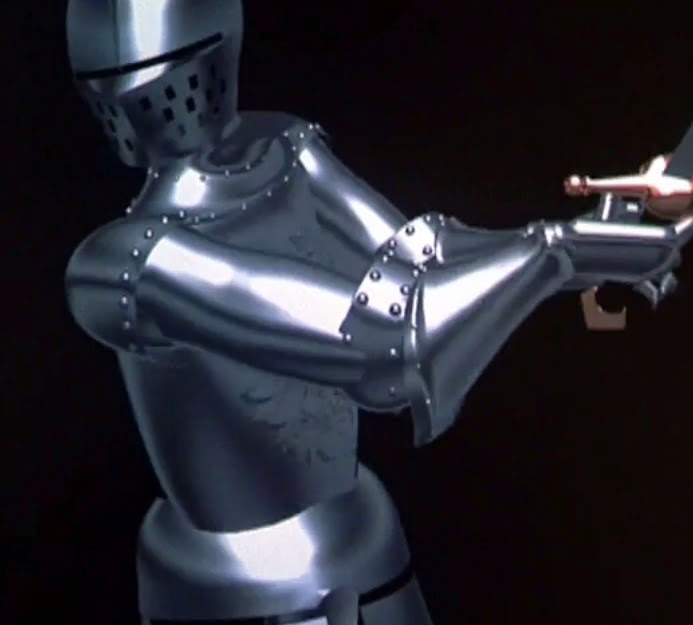

50 Years Ago: The Ultimate Warrior (1975)

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Monday, September 29, 2025

40 Years Ago: Amazing Stories (1985)

First, we see an ancient Egyptian construction, a tomb perhaps, and witness a scroll unfurl, with a story inscribed upon it.

The CGI here may look primitive today, but it still gets the job done. The imagery reminds us of the role that the written word, and storytelling, have played in human civilization across the centuries. In this span, words on a page are a way of maintaining history, and sharing favorite tales.

We're not just countenancing run-of-the-mill stories then, the imagery suggests, but amazing, wondrous ones.

Say what you want about the quality of the actual stories depicted on this Steven Spielberg TV series, the introduction remains an inspiration, and a wonderful journey through the history of storytelling.

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Sunday, September 28, 2025

60 Years Ago: Ghidrah The Three Headed Monster (1965)

In this new identity, Selina warns the people of Earth of an impending crisis, a repeat of the very one that destroyed her advanced home world.

“Godzilla, what terrible language!”

They both hate mankind, and remember, importantly, that mankind hates them. Why should they help?

Mothra, Godzilla and Rodan all demonstrate the capacity not merely for growth, but for cooperation. They are able to rally to a cause greater than themselves, in other words.

By contrast, King Ghidorah is really a berserker with no value system beyond destruction.

And if so, is it a corruption of the franchise’s original idea?

Man has and will continue to achieve advances in terms of his technology, and his capacity for war. But if he brutalizes nature in that evolution, nature will have its revenge, and man will, in that conflict, lose.

Ghidorah, in essence, here takes on the role of Godzilla from the first film. He is Out-of-Whack Nature Personified: a threat that can’t be reckoned with in terms of technology or conventional war.

To some, this approach of giving the monsters human personalities may seem silly or childish, but in a way, this creative choice perfectly expresses the childish nature of the Cold War conflict.

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Saturday, September 27, 2025

40 Years Ago: The Twilight Zone (1985 - 1989)

Yes, you have just entered...The Twilight Zone....lite.

The 1985-1986 TV season actually saw several anthologies debut on network television, and none of them were particularly good.

But during the first two years on CBS, talented executive producer Phil De Guere and a stable of terrific writers made a serious, well-intentioned effort to update the classic series. Harlan Ellison was aboard (briefly) as a creative consultant, and well-known directors such as William Friedkin, Wes Craven and Tommy Lee Wallace helmed standout episodes. I watched this series religiously as a teenager (I was sixteen years old), and still have nostalgic memories. Honestly, you can tell everyone was giving the new series their all, but this new Twilight Zone has not -- for the most part -- aged well.

First off, I blame that fact on the uninspiring look of the series. Most of the episodes ("Nightcrawlers" excluded) resemble dreamy 1980s commercials for feminine hygiene products. There's no distinction, no originality in the visual component of the series, and so you can watch an episode and not be certain whether you're watching Simon & Simon or The Twilight Zone.

Even back in the black-and-white age, there was no mistaking the crisp, black-and-white canvas of the original Twilight Zone for anything else (One Step Beyond, for instance, aired simultaneously, but it lingered more on long shots and featured fewer close-ups).

The 1980s Twilight Zone doesn't win plaudits for internal consistency either. Serling's opening and closing statements on the original series always let you know where you were, who you were with, and why you were there. There was no hedging. On the new Twilight Zone, some episodes included back and front end narrations, some had no narrations whatsoever ("Nightcrawlers"), and some - oddly - featured an opening narration but yet no closing narration ("A Little Peace and Quiet.") Often times, you couldn't tell what the hell the narration was talking about, either.

Charles Aidman narrated the new Twilight Zone (when there was a narration), and he did a fine job. His voice was sweeter, more whimsical more grandfatherly than the rat-a-tat machine gun-style of Serling.

Rod Serling wrote something like ninety episodes of the original Twilight Zone. He was narrator for all of them. He also rewrote various episodes by other superb writers and produced the entire five year series. Considering his ubiquitous presence, it's fair to state that the Twilight Zone represented (primarily) his voice, his morality, his artistic sensibilities. Since he was gone by '85, the new series had no choice but to find its own voice.

"All you have to do is want me," the boy tells her pitifully. Yikes! The sweet little boy (Scott Grimes) asks his would-be mother why she does not want to have him; why she does not love him, and it's all so madly extreme that you expect Pat Boone to show up and lecture us about the evils of abortion.

Yet, the same episode entirely lets the boy's would-be father, Greg, off the hook. Why isn't he haunted by the son he chooses not to have? Why just her?

Off the top of my head, I can't think of even one 1960s Twilight Zone episode that is so blatantly sexist, or that has aged this poorly.

Pack your bags, Zoners...we're going on a guilt trip! "Little Boy Lost's" ending narration backs away from the sexist interpretation of the episode as fast as it can, calling the story simply "a song unsung," "the wish unfulfilled," but it's too little, too late.

Watching this episode, I was reminded of a comment on Serling's particular and singular ethos, one made at his eulogy: "He showed us people maybe we'd rather not think about. But with that keen perception and sparse dialogue, he grabbed you...and told you in no uncertain terms that these people deserved at least a little victory, breathing space, someone to care about them."

"Shatterday" is another signature episode that fails dramatically. And that's a surprise, especially considering all the name talent involved. Wes Craven directs a short story by Harlan Ellison (adapted by Alan Brennert). And the installment stars a very young Bruce Willis as one Peter J. Novins, an ostensibly argumentative man who "pushes" people until one day the world "pushes back." He's in a bar one evening when he telephones his apartment and a doppelganger picks up on the other end. Turns out this doppelganger is a better Peter J. Novins than he is; and that this enigmatic double is setting right all the mistakes of his life. Meanwhile, our Novins starts to fade away, "becoming a memory."

Personally, I love the ideas lurking in this vignette. I love the notion of a doppelganger; and the conceit that someone else might live your life better than you can. But, alas, "Shatterday" never actually dramatizes Peter Novins being a bad guy. The story picks up immediately before the terrifying phone call. As a result, we're told he is a "pusher" (meaning a nudge, I guess?) and a bad guy, but we never see it play out. All of Peter's actions in the episode are actually readily understandable, given that he believes an impostor is taking over his very life, aren't they? Wouldn't you push back too?

Allow me to make another invidious comparison to the original series. It would not have made sense, for instance, in the Serling episode "The Silence," if we had met the lead character there after he had made a bet to stop speaking aloud for a year's time. No, we had to see the loquacious central character babbling mindlessly and egotistically for a time, so we would understand the torture that he would go through in the course of the narrative. We had to understand the crimes of the jabberwocky before we got to see his sentence handed down by the mechanism of the twilight zone.

I hate to write negative reviews, especially about a series as good-intentioned and diverse in storytelling as this eighties Zone.

The thing of importance here: this "little guy" has been dealt a raw hand (as the little guy often is). But he's not going to stop fighting. He's not going to be defeated by it. "Wordplay" reminds us that the human spirit -- nay, the American spirit - is indomitable.

"Nightcrawlers," is another stand-out installment, one which concerns PTSD and the repressed horrors wrought by the Vietnam conflict. It depicts a compelling and nightmarish story set at a small diner just off the highway, a perfect setting for The Twilight Zone. It is blackest night -- with incessant rain pounding -- as the tale commences. A cocky police trooper (Jimmy Whitmore Jr.) who avoided service in Vietnam enters the diner, recounting to a waitress and the cook a harrowing story about the bloody aftermath of a strange motel shoot-out. He's clearly shaken by what he's seen.

As more travelers (including a family) seek solace from the violent storm, events in the diner take a weird turn. A nervous man named Price (Scott Paulin) arrives and is almost immediately revealed to be highly disturbed. He's a Vietnam veteran, you see, and was once part of an elite unit called "Nightcrawlers." Price was traumatized by one particular night mission against Charlie, one which cost the lives of several American soldiers. That night's horrific events remain so resonant with Price that he has developed an unusual power:the ability to manifest his terrible memories...in the flesh.

When Price sleeps (or is unconscious for any reason) his violent nightmares of 'Nam are granted substance and then run amok (which accounts for the motel massacre). Price and the trooper don't get along, and after a verbal confrontation, the trooper knocks Price out. His unconscious state paves the way for a violent dream that transforms this 1980s diner into a jungle landscape, one wherein armed soldiers are on a brutal mission to kill everyone. The episode culminates with a maelstrom of destruction and gun-fire, and the chilling promise that other veterans like Price are out there.. ones with the same destructive "power" and memories.

Boasting a heavily de-saturated and grainy look (the contrast was adjusted by Friedkin himself, according to the episode commentary), this is a Twilight Zone episode that looks more like Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre than it does the average installment of a popular TV series. This is an appropriate touch, because we're subconsciously reminded of authentic Vietnam War footage, and the grainy look it often boasts..

Utilizing just one set (the diner), Friedkin builds escalating tension by focusing on two visual flourishes; ones that he often deploys in his films: insert shots (to create a sense of detail, mood and texture), and extreme close-ups (to draw us into the world and troubles of the characters). On the former front, we get a tour of the diner's seemingly mundane terrain (including coffee cups filled with steaming coffee, cigarette lighters and the like). On the latter front, we are treated to a sustained, highly-upsetting close-up of the mad Price: red-eyed and psychotic; and growing ever more upset. This shot lasts a long time -- beyond all reason, actually -- and is highly disturbing. Friedkin's decision to hold the close-up (in conjunction with Paulin's committed performance) sells thoroughly the notion of this man's insanity.

The theme underlying Nightcrawlers is that for the men who witnessed atrocities and horrors in the Vietnman War, the conflict is never truly over. This notion was just bubbling to the surface when this episode of The Twilight Zone was made. It entered the American lexicon during the Reagan 80s as "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder" (or PTSD) and never left, although a similar syndrome had once been known as "shell shock." Still, the idea was that we had a generation of men "coming home" in the late 1970s who had seen such horrible things that they could never again lead what we non-combatants consider a normal life. And worse, their problems were being ignored by the government, the citizenry, and even the media.

Remember what Freud stated so memorably: that "the repressed" returns as "symptoms." Nightcrawlers makes literal that notion. The only way Price can "exorcise" the demons of Vietnam is to produce those vivid demons in our reality. So what we have in Nightcrawlers is a genre metaphor for PTSD, down to the idea that - if left unexorcised - the violence unleashed in Vietnam will claim more victims here at home.

In the new series, you can spot a brief, almost subliminal flutter of Serling's iconic b&w visage in the opening credits, and that's all.

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of the web series Abnormal Fixation (2024), the audio drama Enter the House Between (2023) and author of 35 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

50 Years Ago: Doctor Who: "The Seeds of Doom" (January 31, 1976)

50 Years ago, Doctor Who began airing one of my all-time favorite serials, "The Seeds of Doom." In Antarctica Camp 3, several sci...

-

Last year at around this time (or a month earlier, perhaps), I posted galleries of cinematic and TV spaceships from the 1970s, 1980s, 1...

-

The robots of the 1950s cinema were generally imposing, huge, terrifying, and of humanoid build. If you encountered these metal men,...