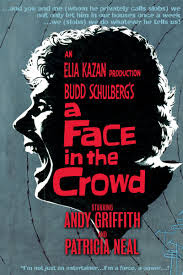

Based on the 1955 short story by Bud Schulberg, “Your Arkansas Traveler,” Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd (1957) is the cautionary tale of an American demogogue’s rise to -- and fall from -- power.

A demagogue might be defined, broadly, as a “political leader who seeks support by appealing to popular desires and prejudices rather than rational argument.”

The film focuses on "Lonesome" Larry Rhodes (Andy Griffith), a small-time crook and fraud plucked from obscurity in a county jail in Arkansas by a radio programmer, Marcia Jeffries (Patricia O’Neal). She is seeking “local color” for her radio show, and Rhodes can spin a story and sing a folk tune like no other.

Marcia's search for an audience -- ratings, in modern lingo -- gives the charismatic but malicious Rhodes both exposure and a public platform. Before long, he’s moved to a bigger radio market. Then he transitions to national TV, talking politics and “telling it like it is” to a receptive, low-information audience that hangs on his every word and believes his every (false) piety.

Rhode’s rise to fame and fortune is aided and abetted by his sponsors and his network. They see his viewership swell to 65 million people. That's a lot of consumers who will buy products from sponsors.

Marcia's search for an audience -- ratings, in modern lingo -- gives the charismatic but malicious Rhodes both exposure and a public platform. Before long, he’s moved to a bigger radio market. Then he transitions to national TV, talking politics and “telling it like it is” to a receptive, low-information audience that hangs on his every word and believes his every (false) piety.

Rhode’s rise to fame and fortune is aided and abetted by his sponsors and his network. They see his viewership swell to 65 million people. That's a lot of consumers who will buy products from sponsors.

A drunk, misogynist, mean-spirited narcissist, Rhodes appreciatively soaks up all the adoration and power, coming eventually to believe his own press.

Eventually, he grows so powerful that he advises a presidential campaign in the art of slogans and sound-byes. He also begins hosting a political program, shrouding extreme right wing isolationist views under the soothing umbrella of Southern-fried common sense.

Eventually, he grows so powerful that he advises a presidential campaign in the art of slogans and sound-byes. He also begins hosting a political program, shrouding extreme right wing isolationist views under the soothing umbrella of Southern-fried common sense.

Eventually, Marcia realizes the key to Rhodes’ downfall involves revealing his true colors to the masses that worship his “home-spun” wisdom and apparent “truth telling.”

As that synopsis makes clear, A Face in the Crowd is a terrifying story of what can happen to America once “politics has entered a new stage: the TV stage.”

One man’s hateful, ignorant words -- not to mention resentment and anti-intellectualism -- finds purchase in the psyches of millions of like-minded people. Kazan’s camera cuts, at one point to a veritable forest of TV antennae jutting upwards from the rooftops of an urban jungle in order to make his point. These receiving devices look like metal weeds, growing and stretching upwards to the sky.

The point, of course, is how the mass media can instantly amplify -- for its own enrichment -- one voice to a volume previously unimaginable in human history. Even Rhodes himself -- in a rare moment of apparent self-awareness – recognizes the danger inherent in this technology and its ability to broadcast an entertaining (albeit dangerous) voice to million.

“Power,” he says, “it’s dangerous. You gotta be a saint.”

One man’s hateful, ignorant words -- not to mention resentment and anti-intellectualism -- finds purchase in the psyches of millions of like-minded people. Kazan’s camera cuts, at one point to a veritable forest of TV antennae jutting upwards from the rooftops of an urban jungle in order to make his point. These receiving devices look like metal weeds, growing and stretching upwards to the sky.

The point, of course, is how the mass media can instantly amplify -- for its own enrichment -- one voice to a volume previously unimaginable in human history. Even Rhodes himself -- in a rare moment of apparent self-awareness – recognizes the danger inherent in this technology and its ability to broadcast an entertaining (albeit dangerous) voice to million.

“Power,” he says, “it’s dangerous. You gotta be a saint.”

But as the film makes plain, Rhodes is no saint.

His father was a con-man who abandoned the family, and one feels that this is the galvanizing influence in Rhodes’ life. He has never been able to get past his father’s actions, or feel truly confident in himself. Accordingly, he hates authority in all its forms. He hates his father, who abandoned him. He hates the law, which punishes him for infractions. He hates establishment figures, who possess the power he covets.

Rhodes also hates those who are smarter than he is, like TV writer Mel Miller (Walter Mattthau). Miller represents the education and knowledge that could expose Rhodes as the ignorant lout he is.

His father was a con-man who abandoned the family, and one feels that this is the galvanizing influence in Rhodes’ life. He has never been able to get past his father’s actions, or feel truly confident in himself. Accordingly, he hates authority in all its forms. He hates his father, who abandoned him. He hates the law, which punishes him for infractions. He hates establishment figures, who possess the power he covets.

Rhodes also hates those who are smarter than he is, like TV writer Mel Miller (Walter Mattthau). Miller represents the education and knowledge that could expose Rhodes as the ignorant lout he is.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the film involves Miller’s impotence in the face of Rhodes’ continuing disdain and hatred for him. We are led to the conclusion that is easier for a demagogue to to hate and attack than it is for a rational person to respond meaningfully to that demagogue.

That’s undoubtedly because demogogue’s rely on powerful emotions (anger, rage, resentment) and mob-like followers who repeat mindlessly their every word and slogan. Educated intelligent people are like deer in a headlight by comparison, making logical cases and appealing to cerebral arguments.

That’s undoubtedly because demogogue’s rely on powerful emotions (anger, rage, resentment) and mob-like followers who repeat mindlessly their every word and slogan. Educated intelligent people are like deer in a headlight by comparison, making logical cases and appealing to cerebral arguments.

Miller simply can’t conceive of the fact that a nativist, bigoted simpleton could have a better innate understanding of human nature and human foibles than he does. But Miller knows what makes his people tick.

Importantly, Miller fails to fully understand his role in Rhodes’ rise. Like Marcia, he is culpable for elevating a demagogue to the status of national treasure. Rhodes is a distraction, a joke, a fad when it is good for Miller’s wallet or career.

Only later is the coarseness of the superstar a danger to freedom itself.

Importantly, Miller fails to fully understand his role in Rhodes’ rise. Like Marcia, he is culpable for elevating a demagogue to the status of national treasure. Rhodes is a distraction, a joke, a fad when it is good for Miller’s wallet or career.

Only later is the coarseness of the superstar a danger to freedom itself.

What’s amazing about Rhodes, the film subtly observes, is the yawning chasm of cognitive dissonance between his public “persona” and his real personality.

Rhodes lives in a luxurious penthouse apartment, surrounds himself with wealth and women, and covets his TV ratings. In short, he is a coddled, entitled rich man. But his public shtick -- his fake, media-driven image -- is as “The voice of grass roots wisdom.”

On stage, he voices syrupy Christian platitudes like “the family that prays together, stays together,” from his humble “cracker-barrel” sound stage. In real life, he is a philanderer who marries a 17 year old girl and then cheats on her.

In real life, he is also being supported by a political establishment that wants his audience’s votes.

So Rhodes is a text-book fraud.

He pretends to be a common-sense, salt-of-the-earth, plain talker when in fact he is a messenger boy for the wealthy elite. Rhodes claims he believes in the common man, but he hates and derides the common man.

His ambitions are bottomless. “The whole country is just like my flock of sheep,” he enthuses at one point.

Rhodes lives in a luxurious penthouse apartment, surrounds himself with wealth and women, and covets his TV ratings. In short, he is a coddled, entitled rich man. But his public shtick -- his fake, media-driven image -- is as “The voice of grass roots wisdom.”

On stage, he voices syrupy Christian platitudes like “the family that prays together, stays together,” from his humble “cracker-barrel” sound stage. In real life, he is a philanderer who marries a 17 year old girl and then cheats on her.

In real life, he is also being supported by a political establishment that wants his audience’s votes.

So Rhodes is a text-book fraud.

He pretends to be a common-sense, salt-of-the-earth, plain talker when in fact he is a messenger boy for the wealthy elite. Rhodes claims he believes in the common man, but he hates and derides the common man.

His ambitions are bottomless. “The whole country is just like my flock of sheep,” he enthuses at one point.

Delightfully, A Face in the Crowd provides a prescription for the destruction of Rhodes and demogogues just like him.

Realizing she has created a monster, Marcia turns up the studio sound during a live broadcast, and she lets Rhodes hang himself on-air. Believing the sound is off, Rhodes expresses his true feelings for his audience. “I can make ‘em eat dog food like it is steak!” He reports.

He is so confident in the fact that his followers will mindlessly follow wherever he leads that he actually says he could “murder” people, and they’d still be on his side.

Realizing she has created a monster, Marcia turns up the studio sound during a live broadcast, and she lets Rhodes hang himself on-air. Believing the sound is off, Rhodes expresses his true feelings for his audience. “I can make ‘em eat dog food like it is steak!” He reports.

He is so confident in the fact that his followers will mindlessly follow wherever he leads that he actually says he could “murder” people, and they’d still be on his side.

But that’s not the case. He has overestimated his appeal.

The audience at home finally realizes that Larry is not one of them at all. He is an impostor, and just as much a tool of the hated “elite” as any conventional politician or leader. He has not “told them like it is,” at all.

He has, contrarily, pandered to them in the worst ways possible, and they have taken his words as the God’s honest truth. He has not only played them and abused them at every turn...he has gotten rich doing so.

The audience at home finally realizes that Larry is not one of them at all. He is an impostor, and just as much a tool of the hated “elite” as any conventional politician or leader. He has not “told them like it is,” at all.

He has, contrarily, pandered to them in the worst ways possible, and they have taken his words as the God’s honest truth. He has not only played them and abused them at every turn...he has gotten rich doing so.

Kazan finds a clever visual to express Rhodes’ sudden and dramatic fall from grace. We see the elevator lights going down, quickly, in his apartment building, floor to floor. He starts at the penthouse, and drops to ground level, before our eyes, in seconds. The fall is more than symbolic. It is a meteoric crash he experiences, one even faster than his surprising, relentless rise.

A Face in the Crowd is a terrifying drama in part because of its plausibility. The mass media often gives irresponsible voices of hate, bigotry, and false piety a platform and open mic to influence the nation.

The film notes the media’s inherent culpability for creating such a demogogue, and rightly so. If you willingly invite the devil to dance with you, you can’t complain, later, when you don’t like how he treats his dance partner.

The film notes the media’s inherent culpability for creating such a demogogue, and rightly so. If you willingly invite the devil to dance with you, you can’t complain, later, when you don’t like how he treats his dance partner.

The film also thrives because of Griffith’s unforgettable performance. He portrays a monster of such high energy and narcissistic pride. Rhodes is a monster of considerable charisma and, hauntingly, occasional moments of insight. But he has no loyalty or feelings of responsibility to anyone or anything beyond his own self-glorification. The thought have him possessing real power is terrifying.

A Face in the Crowd is a sobering reminder of how a dangerous, narcissistic demagogue can use and exploit the media (in a symbiotic relationship…) to change the face and values of a whole nation.

But the film also reminds us how to stop such monsters.

Journalists, concerned citizens, politicians, and voters all possess a responsibility to see that his “personality finally comes through,” preferably on the very channel that created him.

“When we get wise to him, that’s our strength,” the film knowingly concludes.

But the film also reminds us how to stop such monsters.

Journalists, concerned citizens, politicians, and voters all possess a responsibility to see that his “personality finally comes through,” preferably on the very channel that created him.

“When we get wise to him, that’s our strength,” the film knowingly concludes.

The question that makes A Face in the Crowd such an intense, anxiety-provoking experience is one for the ages.

What happens if we get wise to the demagogue too late?

What happens if we get wise to the demagogue too late?

To answer that interrogative, one need only look at some of the worst historical tragedies of the 20th century.

No comments:

Post a Comment