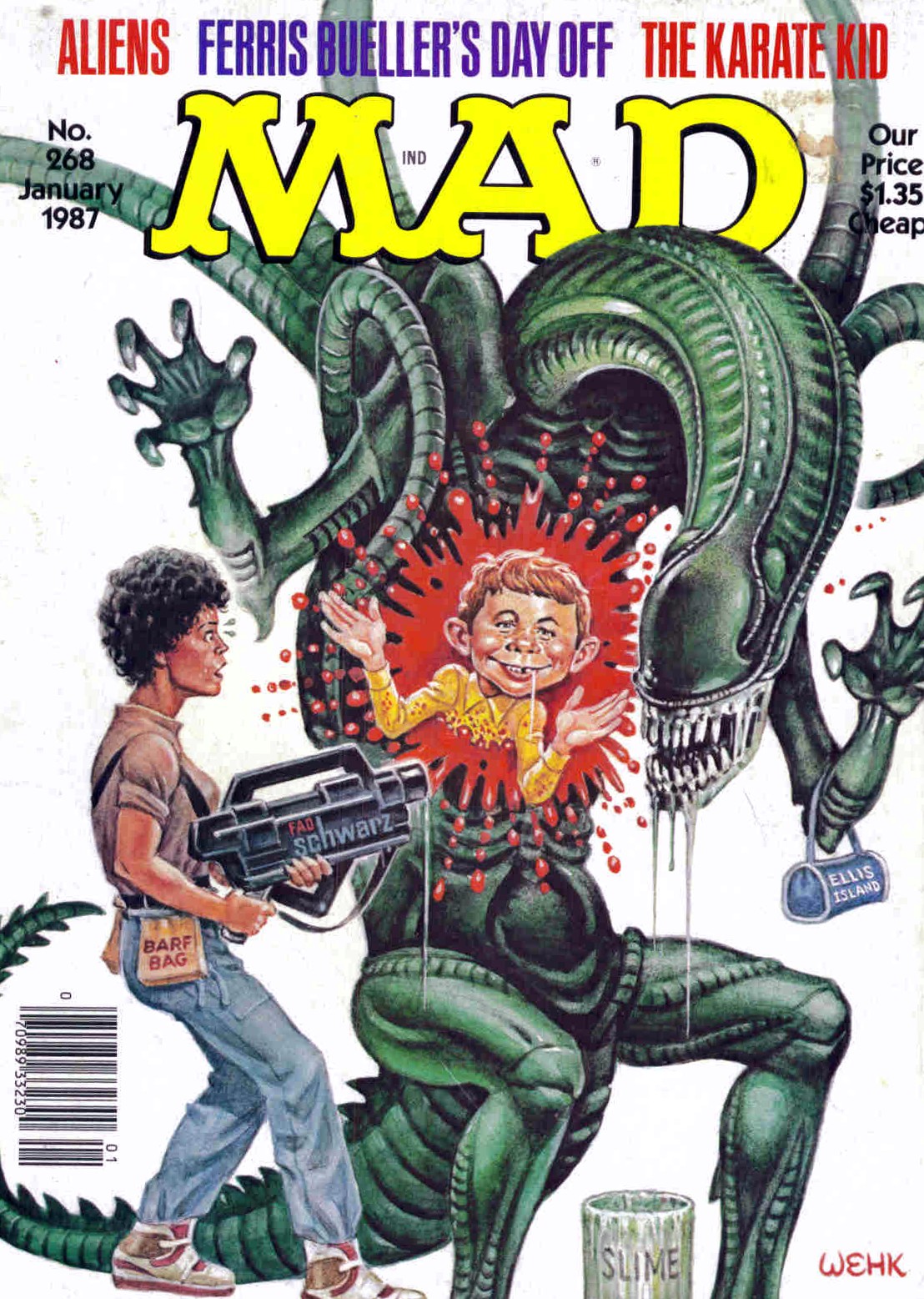

Each of the four films in the Alien franchise (which spans the years 1979 - 1997), represents the work of a master cinematic visualist: Ridley Scott, James Cameron, David Fincher and Jean-Pierre Jeunet.

Each of the four films in the Alien franchise (which spans the years 1979 - 1997), represents the work of a master cinematic visualist: Ridley Scott, James Cameron, David Fincher and Jean-Pierre Jeunet.

Still, there remains some debate on the actual quality of the four series films. The general meme on the franchise is that the first two films are brilliant and the final two are...well...controversial. There seems to be no basis for rational agreement on Alien 3 and Alien Resurrection. In part that is because, I believe, Fincher's film not just defies audience expectations, but actually spits in the face of those expectations. As for Alien Resurrection...it lapses into broad, almost campy comedy at spots (for instance, any time Dan Hedaya is on screen...) and therefore feels - in selected moments - like a deliberate betrayal of the franchise that began with the shiver-invoking tag line "In Space, No One Can Hear You Scream."

I've recently watched all the Alien films again. And, no surprise here, I've found myself fascinated - one might even say obsessed - by Scott's stunning and brilliant original. I realize there are clear antecedents for the "alien on a spaceship" or planet movie (namely Bava's Planet of the Vampires [1965] and Cahn's It! The Terror From Beyond Space [1958]) but there is little doubt that Alien represents the ultimate realization of this theme for a few reasons (not the least of which involve casting and budget).

I've reviewed Alien before and awarded it the highest rating of four stars not merely because it is scary, not merely because it cogently reflects the late 1970s and some latent fears around human reproductive issues, but because it is a brilliantly-designed feature and one that pushed the genre a quantum leap forward. It eschewed the stream-lined, modernism and "neat" future-look of such films as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Journey to the Far Side of the Sun (1969) and offered a "grungy," lived-in future. This is a world where coffee cups rest on computer consoles; where pornography is pinned-up next to technical work stations. Where characters still wear sneakers and ball caps, yet go to sleep in cryo-tubes. These characters (smokers, for the most part), have famously been termed "space truckers" and that's part of the Alien mystique and appeal. Outer space isn't the final frontier in Alien...it's just your day job. Your average blue collar astronaut is still just working for The Man (in this case, Weyland-Yutani, "the Company"), still trying to get his "share" of the wealth. In the far future - as in the present - the Corporation is the enemy.

These observations have been made before, by myself and other critics, but what fascinated me so deeply about Alien on this umpteenth watching is how some of film's most fascinating ideas and implications didn't survive into the remainder of the feature film series. When a movie as popular as Alien is sequelized, some great ideas are dropped and some are co-opted or twisted. Here some essential elements of the original film are - in a sense - retroactively harmed by the very "familiarity" of a franchise. For instance, by the time of Alien Resurrection, we all know the life-cycle of the alien creature by heart: egg, face hugger, chest burster, Drone. In other words, we know precisely what to expect of the alien in all of its form, thus undercutting the very alien-ness" of the titular creature.

Consider, for just a moment, what it must have been like to see the original film in the theater in 1979 with no fore-knowledge of this life cycle. It is only when you indulge in this exercise that you begin to understand the impact and importance of Alien as a horror film. Virtually every time you see the "creature" in Scott's movie, it is in a different form (and I submit, they are all pretty horrifying...). Today, we watch the film and we know precisely what's coming; back in 1979, you'd watch the film and have no f'ing clue what the creature was going to be the next time it appeared. This created tension and a high level of anticipatory anxiety.

"A perfect organism," Ash (the science officer of the Nostromo) calls the Alien. It is a creature whose "structural perfection" is matched only by its "hostility." It is a creature unencumbered by "conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality." In some ways, this genius description of the xenomorph is forsaken as the Alien films trot along their way and more and more "human" motivations are ascribed to the beasts. Consider, in Aliens (1986), we see the monsters in a "hive" protecting their "Queen" so we come to understand them not as something "alien" but as larger-than-normal insects. Consider that in Alien Resurrection, we see the aliens mistreated (by a scientist played by the incomparable Brad Dourif) and even develop a degree of sympathy for them...again undercutting the very alien-ness of the breed. Familiarity may not breed contempt...but it breeds...familiarity (which tends to be fatal for horror films and for the ability to scare an audience).

Consider also that the alien in Scott's original film is not merely strong, but absolutely, undeniably unkillable. It's true that most of the Nostromo crew never lays a glove on the xenomorph (not even the hyper-physical Parker), but even when Ripley ignites the engines of the shuttle Narcissus on the evacuated Alien during the film's denouement...it does not die. It just sort of...floats away into space. The obvious implication is that the xenomorph is unkillable and all you can hope to do is get away from the bloody thing. You might be able to fight it to a stand still, but you will never kill it. Down to the blood of the creature (molecular acid), the creature is designed to survive ("hell of a defense mechanism...you don't dare kill it," Parker notes.) Scott is a skilled enough director that had he wanted to feature the destruction of the alien, he would have done so in a way that was recognizable and highly visual. Instead, the adult-alien just sort of floats towards the camera in a mini-montage. Again, this isn't an accident. We are meant to see that the alien survives the considerable power of the engine ignition.

This is one of the (important) things lost in the sequels. In Aliens, the space marines go in and blow up the xenomorphs by the dozen. Our smart guns, flame throwers, and pulse rifles do the trick rather nicely (though watch out for spraying acid...). This is highly exciting, I might add, but utterly inconsistent with the first film. The central idea of Ash's "perfect" life form is lost. Perfection - by very definition - must include immortality. By the time of Alien Resurrection, Winona Ryder (!) and even a man in a wheelchair are blowing away Aliens. No longer are they the "perfect" creature depicted in the original. They have been caged, frozen, burned, blown apart, and even ripped apart (by the Newborn).

Ridley Scott and the writers of Alien (Dan O'Bannon, Ronald Shussett, David Giler, Walter Hill, etc.) devised another element of the Alien's "perfection" back in the late seventies, namely the fact that it boasted a completely self-contained life-cycle. In the original concept, eggs hatched face huggers, face-huggers laid chest-bursters, chest-bursters grew to "adult" size and the adult would "cocoon" prey and transform that prey...into eggs...which would then start the cycle all over again. The alien was thus able to use whatever materials were on hand and available (whether human or alien - like the space jockey on LV-426) to perpetuate their existence. Again, when Cameron came to Aliens, he "ret-conned" the life-cycle to include a conventional creature, a Queen. So after his film...no Queen, no alien perpetuation, right? (And I submit, this is one of Alien 3's true deficits: what is the alien soldier on Fury 161 actually doing to its bar-coded prey? Without a queen, the Alien can have no "purpose.") This is a prime example of how a discarding of a single idea has tremendous repercussions across the three sequels. One can argue, based on the murder of the doctor (Charles Dance), that the alien is protecting Ripley, mother-to-be of a Queen, but this idea is not wheeled out in anything approaching a consistent fashion.

An amazing aspect of 1979's Alien, one that makes it ceaselessly worthy of new examination is the fact that it includes several incredible storyline implications just beneath the surface...present, but unexplained. Take for instance the derelict ship that the Nostromo finds on LV-426. It is emitting a distress call (or actually, a warning: stay away), and when Dallas, Lambert and Kane investigate it, they see the dead pilot, the "space jockey" with a torn-open chest. They also find a giant lower chamber (which I submit MUST BE a cargo hold, given its dimensions and relative lack of instrumentation, furniture, etc.) that is filled with eggs. The eggs are ensconced underneath a level of fog which "reacts" when broken.

So the question becomes: who were these aliens transporting eggs in the first place? And why were they transporting alien eggs? Even more so, since the space jockey's chest is erupted, what became of the alien adult that was born inside it? My notion is that the space jockey's race developed the aliens as a bio-weapon (maybe they are weapons dealers?) and that an accident caused one of the breed to be infected. Similarly, I believe that the eggs would never have hatched in the first place without Kane's interference because they were likely in some kind of "freezer" or "stasis" chamber, as evidenced by the layer of blue fog. I mean, if you were transporting deadly xenomorphic weapons from one planet to another, wouldn't you have safeguards? Wouldn't you have the eggs on ice, at least metaphorically? Again...none of this is explained in the film; only hinted at, and again this lack of clear answers adds to the "alien-ness" of the situation. Our people, seven unlucky human beings, happen by (on secret Company Orders), and get pulled into a much larger, largely unexplained drama.

Of course, if my theory is correct, you're led into a whole round of new and tantalizing questions. If the aliens were a "delivery"...who was the buyer? And who was that race fighting that they would unleash these monstrous aliens on them? And if they planned to unleash aliens, how did they also plan to control them? And how long ago did this all happen? The space jockey appears fossilized. So were the alien xenomorphs soldiers (or weapons...) involved in a war that was waged and either won or lost all before mankind was born? AVP provides a little detail on alien history with Predators, but it is mostly disappointing, even if it does explain how the Company knew to send the Nostromo to LV-426. One big unanswered question still: if a chestburster broke out of the space jockey, then where is that adult alien when Dallas and the others arrive. Hmmm....

See how the film is just loaded with implications above-and-beyond the "ten little Indians" template of an alien killing astronauts on a spaceship? The deeper you delve, the more interesting it becomes.

Alien is well-known for the gory chest-burster scene featuring John Hurt, but it also features one of the creepiest off-screen deaths of all time, and another discarded idea in the franchise. When last we see Lambert (Veronica Cartwright), the xenomorph's prehensile tail is seen winding its nefarious way up between her legs. Then, the film cuts to Ripley running down a corridor, but we still hear Lambert panting, and some...inhuman moaning. So what the hell is going on here? What is the alien doing to her? Does it, by its very "perfect" nature boast some other form of reproductive ability that it is...uhm...practicing on her? Is it fulfilling some kind of sexual desire? Again, Alien Resurrection brings this idea full circle when the Alien Queen - who now has human DNA - gives birth from a womb, rather than laying an egg. But the very shape and potential of human/xenomorph mating is hinted at as early as the 1979 original. And then dropped like a hot potato from the franchise for twenty-five years.

There are sub-texts and social commentary in all the Alien films. Aliens offers us two opposing visions of "motherhood" (one human, one alien), and Alien 3 daringly acknowledges that there are some things more important than survival, and that the true test of a hero often comes when you have no friends, no weapons, and must rely only on your own sense of morality. Alien Resurrection asks "what does it mean to be human?" But once more, the original Alien seems to have the most on the ball in terms of nuanced subtext. In particular, the film has a queasy, uncomfortable undercurrent involving our sexuality. On the surface, the film concerns a creature that can pervert our reproductive cycle for its own ends. But underneath - if we peel back the layers - there are moments in Scott's original that involve homosexuality, sexual repression, and more.

Consider that John Hurt's character Kane becomes the first recipient of the alien's reproductive advances. Whisper-thin, British and sexually ambiguous, Kane is depicted - at one point in the film - wearing an undergarment that appears to be a girdle; something that is distinctly "feminizing" to him. Also, Kane lives the most dangerous (or is it promiscuous?) life-style of anyone amongst the crew. He is the first to waken from cryo-sleep, the first to suggest a walk to the derelict, and the only man who goes down into the egg chamber. He is well-acquainted with danger as (stereotypically...) one might expect of a homosexual man circa 1979. (Note: I said "stereotypically" so don't send the PC police after me, all right?)

As though the alien understands Kane's sexually-ambiguous, possibly homosexual nature, it is Kane who is made unwillingly receptive to an oral penetration: the insertion of the face-hugger's "tube" down his throat...where it lays the chest-buster. What emerges from this encounter is "Kane's son" (in Ash's terminology). But essentially, the alien forces Kane - a homosexual male by nature, to act in the role he might be familiar with; that of female. It's rape, of course, but it's more than that too.

Consider Ash, as well and this character's sexual underpinnings. He is actually a robot - a creature presumably incapable of having sex, and the film's subtext suggests that this inability, this repression of the sexual urge, has made him a monster too. When he attacks Ripley late in the film, Ash rolls up a pornographic magazine (surrounded by other examples of pornography) and attempts to jam it down her throat...it's his penis surrogate. The implication of this particular act is that he can't do the same thing with his penis, so that Ash must use the magazine in its stead. Later, Ash admits to the fact that he "envies" the alien (penis envy?) and one has to wonder if it is because the alien can sexually dominate any creature in a way Ash cannot manage. When Ash is unable to sate his repressed sexual desire with Ripley, the pressure literally causes him to explode: the android blood is a milky white, semen-like fluid. And it spurts everywhere...a true ejaculation. Ash, when confronted with his own sexuality and inability to express it...can't hold his wad.

The most hyper-masculinized (again, stereotypically) character in Alien is Parker (Yaphet Kotto), a black man who brazenly discusses eating pussy during the scene leading up to the chest-burster moment. He has an antagonistic, adversarial relationship with Ripley, and is the character most often-seen carrying a weapon (a flame thrower). In another film, Parker might be our hero. In fact, he dies because of the stereotypical quality of chivalry, in a sense: he won't turn the flame thrower on the alien while a woman (Lambert) is in the line of fire. The alien dispatches Parker quickly (mano e mano), perhaps realizing he will never co-opt an alpha male like Parker to be his "bitch;" at least not the way Kane was used.

As for Lambert, the most-traditionally (and - again - stereotypically) female character in the film -- she gets raped by the alien as I noted above, presumably by the xenomorph's phallus-like tail. Again, the alien has exploited a character's biological/reproductive nature and used it to meets its own destructive, perverse needs.

Which brings me at long last to Ripley. A character role written for a man and played by a woman (Sigourney Weaver). She is the only survivor (along with Jones the Cat), of the alien's rampage on the Nostromo, and there's a case that can be made that the alien cannot so easily "tag" Ripley as either male or female, and that's why she survives. Kane is fey (possibly gay), Ash is a robot (and hence not able to express sexuality in a "normal" way), Parker is all man, and Lambert is all woman...but Ripley is a tall glass of water (practically an Amazon), and an authority figure (third in command). She is also the only character who balances common sense, heroism, and competence. Given this uncommon mix of stereotypically male and female qualities, the alien is not quite sure how to either "read" or "use" Ripley. In the final moments of the film, it does make a decision; it recognizes Ripley - the best of humanity whether male or female - as kindred; a survivor. So it rides (in secret) with her aboard the shuttle Narcissus as they escape the exploding Nostromo. Note that the alien could likely kill Ripley any time during that flight...but does not choose to do so. It knows it is in safe hands with her, at least for the time being. It uses her "competence," her skill (qualities of itself it recognizes in her?) to escape destruction...again proving its perfection. Here, perfection can be judged by how well it understands the enemy, the prey.

So, underneath the scares and underneath the great design, what we have here in Ridley Scott's Alien is the story of a monster that exploits our 1970s views of biology and psychology; causing us (as viewers) to re-examine, perhaps even subconsciously, the sexual stereotypes of the day. The alpha males (Dallas and Parker) are ineffective, the traditional "screaming" female gets exploited (not rescued...), and the most "evolved" human, Ripley (along with another perfect creature - a cat) survives to fight again (and again...and again...and again, as a clone). The strange, spiky sexual nature of Alien lurks just beneath the surface of the film, and is noticeable even in the set design. Just take a long, hard (forgive the term...) look at the "opening" of the alien derelict...it is pretty clearly a vagina. And the chest-burster is pretty clearly phallus-shaped. Ask yourself why. Sex, and sometimes discomfort with sex - is at the heart of this horror film.

You might say I'm reading too much into the film, but nonethtless I suggest one implication of Alien (one quickly cut loose by the more mainstream sequels), is that human sexuality unloosed is the real monster from the id.